THE SUSHRUTA SAMHITA

THE SUSHRUTA SAMHITA

In the text, Rishi Sushruta stresses that

‘Theory without practice is like a one-winged bird that is incapable of flight.’

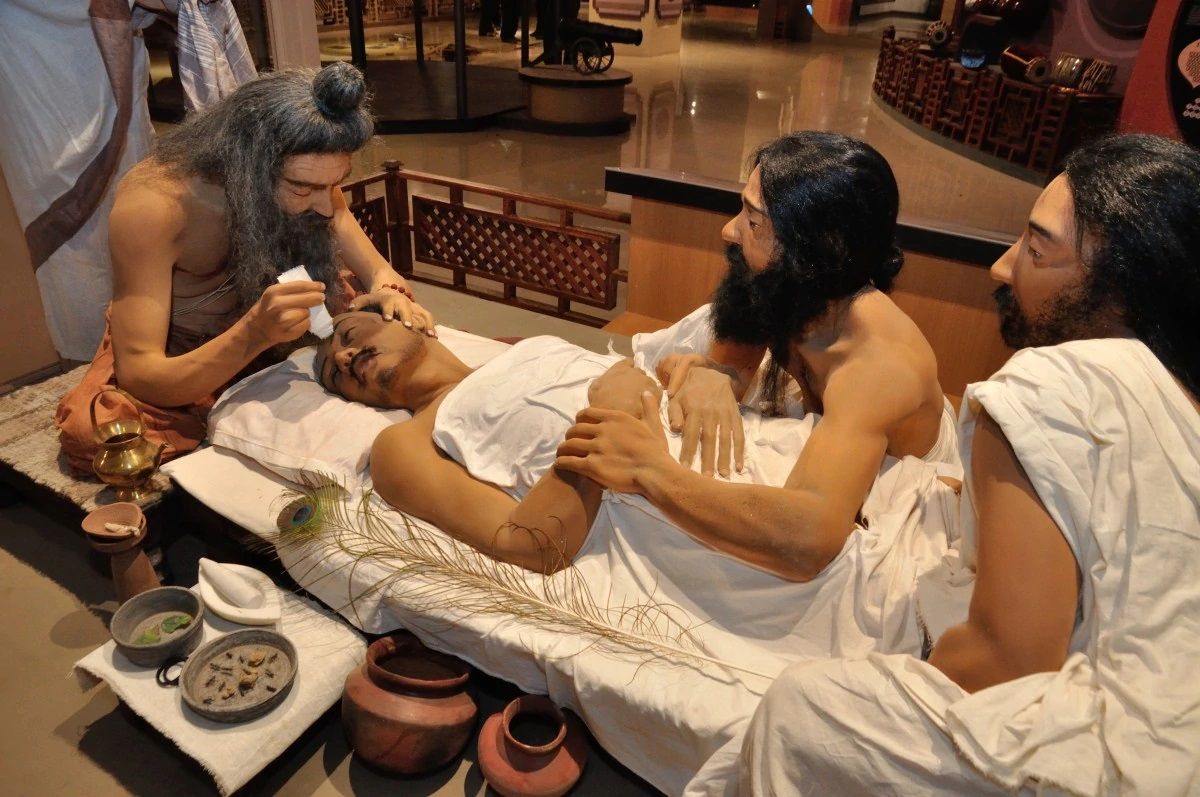

He was one of the earliest known medical teachers in the world to advocate that the dissection and study of dead bodies was a must for any successful student of surgery. The students of Sushruta began by practicing incisions and excisions on vegetables and fruits and also leather bags filled with mud or liquids of different densities. This was then followed by practice on corpses of animals and then human beings.

This was tricky as the orthodox Hindu tenets according to the Dharma Shastras considered the human body sacred, so much so that it was stated that it must not be violated by the knife and must be cremated in its original condition. Sushruta and his students subverted this by using a brush-type broom, which scraped off skin and flesh without the dissector having to actually touch the corpse. This enabled them to bypass orthodox restrictions and study the human organs.

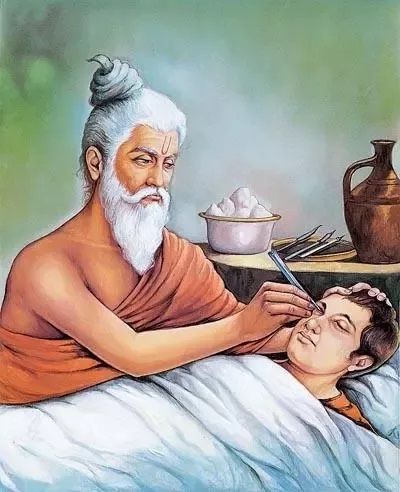

At a time of non-existent biochemical or imaging equipment, Sushruta and his students carried out complicated surgeries like cataract extraction and removal of urinary stones (ashmari). During the procedure, they advocated medicated wine for anaesthesia and laid stress on sterilising the operation room by fumigating it with fumes of mustard, butter and salt.

One of the most interesting aspects of the text is the sheer detailing of rhinoplasty as a technique. Cutting off the nose was a common punishment in ancient India and the text mentions more than 15 methods to repair it. These include using a flap of skin from the cheek or the forehead, which is akin to the most modern technique today. There are also references in Sushruta Samahita to the technique of moulding false legs with iron, now common as the prosthesis.

The treatise also has useful treatment techniques to what we think are very modern day ‘lifestyle’ diseases like ‘Madhumeha’ or diabetes and ‘Hridroga’ or disease of the heart. These ancient surgeons had the knowledge of a structure in the chest and its role in the circulation of vital fluids through the channels. Sushruta Samhita contains classifications of bones, dislocation of joints, fractures, and their treatment. The text also has commentary on paediatrics and midwifery.

Like other great Sanskrit texts, the Sushruta Samahita also traveled from India to other parts of the world. During the early 8th century, the text was translated into Arabic as ‘Kitab Shah Shun al-Hindi’, by an Indian medical practitioner named Mankah on orders of Yahya Barmakid, a powerful minister of Caliph Harun-al-Rashid of Baghdad.

There are also historical references to this in the court of king Yasovarman I (889 CE-900 CE) of Cambodia as well as in the monasteries of Tibet. The first European translation of Sushruta Samhita was published by Hessler in Latin in the early 19th century. The first complete English translation was done by Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna in three volumes in 1907 in Calcutta.

The Sushruta Samhita is a gem in more ways than one. Not only is it a great scientific treatise that has stood the test if time, it is also an iteration of the great strides made in the field of science in Ancient India.

Specifications

Hits | 1282 |

Publisher | Chaukhambha Sanskrit Sansthan |

Downloads | 126 |

Pages | 534 pages |

Year | 2014 |

Author

Author | Susruta Samhita |

Sushruta, one of the founding fathers of surgery and plastic surgery, lived in India sometime between 600 to 1000 B.C. His Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta’s compendium), one of the most outstanding treatises in Indian medical literature, describes the ancient tradition of surgery in India. He lived, taught, and practiced in what presently corresponds to the city of Varanasi (Kashi, Benares), and is remembered especially for his innovative method of rhinoplasty.

Sushruta developed surgical techniques for reconstructing noses, earlobes and genitalia, many amputated as religious, criminal, or military punishment. He developed the forehead flap rhinoplasty procedure that remains contemporary plastic surgical practice; also the otoplastic technique for reconstructing an earlobe with skin from the cheek.