More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

“Music in the soul can be heard by the universe”: Konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally, and often referred to as a "mathematical language" due to the close relationship between the rhythms in Konnakol and mathematical principles

Music and the arts have played a prominent role in the manifestation of Indian culture. Since ancient times Indian music has been associated with religious devotion and been connected to temple rituals and social functions. The origins of Indian music can be traced to the four 'Vedas', an ancient compilation of sacred and religious texts, prayers, hymns, chants, and rituals dedicated to various Gods.

The Vedas have been successfully preserved and passed on by oral tradition, and have been documented in Sanskrit the classical language of India. The Vedas date from approximately 4,000 B.C. - 1,000 B.C. and are divided into four sections the Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, and Atharva Veda (Subramaniam 1990; Sankaran 1994; Karaikudi R. Mani, 1998).

Vedic literature refers to the use of percussion instruments and the use of odd and even meters. The texts and chants were first recited as monotone and then later developed to three notes - a main tone with one tone higher and one below. This development enabled a greater accentuation of words and thus begun the development of the use of meter in Indian music. In the Yajur Veda, the chants developed into four notes - two main notes and two accents.

The Sama Veda is thought of as the most significant in relation to the development of music. It added three more notes and formed the basis of the seven-note scale, thus providing the foundation for Ragam in the development of Indian music (Sankaran 1994; Subramaniam 1990).

In the Samagana -a part of the Sama Vedas - importance was given to tempo using Druta (fast), Laghu (short) Guru (long), and Pluta (lengthened). There is also a reference in Samagana to accentuation and embellishment of words or notes, including rules for the uttering of text to be stressed, lengthened, oscillated, sung, or skipped over. A pause was indicated by the use of a bar sign - I (Kumar Sen 1994).

The following quote from 'Indian Concept of Rhythm' by Arun Kumar Sen, supports the historic importance given to rhythmic development in Indian music.

'From the 6th Century B.C., Kinnaras and Apsaras (dancers in the court of the Gods according to Indian Mythology) were systematically studying laya forms. The tradition of keeping time by counting the matras (time measures) with the hand, in accompaniment to music and dance was prevalent. The women of Yajurvedic times were expert in the science of rhythm (tala) and they displayed it in music and dance.' (Kumar Sen, 1994, p. 2-3)

The music of the Vedas was prevalent throughout India. Over time, and with great dedication from scholars, the music made great advancements. There is mention in many history books (cited in the reference section) of various 'Golden Ages' in Indian music and dance, times when the arts flourished, when great developments were made, and '...when the imagination of a kingdom without dance, music and the playing of percussion instruments was impossible.' (Kumar Sen, 1994, p. 4) It is important to acknowledge the long and rich history of this highly sophisticated system of music. For thousands of years at the core of its growth, there has been a dedicated and almost scientific approach applied to the development of Indian music.

It is also important to remember that throughout this development not only did the science of Talam develop but also that of Ragam. Indian classical music is modal and each composition is set to a Ragam, a selected set of ascending and descending pitches based on the tonic (Sa). The vocal delivery of each Ragam has its own characteristic phrases and interpretation. Each Ragam also has a related emotion, a suitable time of day to be performed, and sometimes an appropriate season for performance.

“Music in the soul can be heard by the universe”: Konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally, and is often referred to as a "mathematical language" due to the close relationship between the rhythms in Konnakol and mathematical principles

Classical Indian music is predominantly an oral tradition with students listening, imitating, and then committing the syllabus to memory. Students rarely ask questions during lessons, rather they are devoted listeners. In the last 100 years or so, notebooks have been used as a memory aid for students, but they are not used in performance.

Traditionally in the study of Indian classical music, there is a highly formal relationship between guru and student and it is considered an honor to receive lessons in music. Historically the system of gurukul existed, where the student would live with the guru as part of the family during the years of study. Today students rarely live with gurus (unless they are relatives) but the relationship remains formal and Indian teachers are very much revered. The guru is often thought of as a spiritual guide as well as a musical one.

Particularly in India, students often travel long distances to learn from a particular guru teaching a favored tradition. Mridangam is a very popular instrument for young boys to learn. They start classes around the age of seven and usually have two or three half-hour lessons per week. As with all classical Indian musical traditions, it takes many years of study to be able to understand and perform the complex variations of the music.

Teachers often wouldn't accept payment for tuition, rather they were content to see their tradition continued by select gifted students. Outstanding musicians were supported by a system of patronage by Maharajas (kings) and wealthy landlords holding private concerts. Over the last 300 years, the teaching of Karnatic music has broadened and gradually people from many casts have been able to make their mark as performers either through the guru/disciple system or by being self-taught.

Today, most outstanding musicians earn their living by giving public concerts where many people can enjoy the music by paying an entrance admission. There are government scholarships awarded to highly regarded musicians and salaried positions for outstanding artists to work as performers with establishments like All India Radio. It is acceptable now for teachers to receive remuneration for providing lessons.

Today students from many casts are permitted tuition and in some cases, scholarships are given to students who may be unable to pay for tuition but show 'promise' and dedication.

Whilst Konnakol is a recognized art form of principle study and has its own position within the percussion section of the Karnatic ensemble, over the last 100 years there has been a diminishing number of artists pursuing principle study in Konnakol. This is probably due to the diminished employment prospects for Konnakol artists as they are seen as extra - rather than essential - members of the percussion section. Due to the diminishing number of Konnakol artists, some percussion artists intersperse Konnakol with their percussion playing to add variation in solo sections.

Konnakol

Konnakol (also spelled Konokol, Konakkol, Konnakkol) (Tamil: கொன்னக்கோல் koṉṉakkōl) (Malayalam: വായ്ത്താരി) is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally in South Indian Carnatic music. Konnakol is the spoken component of solkattu, which refers to a combination of konnakol syllables spoken while simultaneously counting the tala (meter) with the hand. It is comparable in some respects to bol in Hindustani music but allows the composition, performance, or communication of rhythms. A similar concept in Hindustani classical music is called padhant.

Konnakol is an Indian classical art form of reciting percussion syllables which is considered as the ‘mother of all percussive languages, instruments and traditions’. It is perhaps the most complex, intricate, aesthetically designed, advanced vocal rhythmic system in the world, which is unmatched in depth, stature, and range. With its roots deep-seated in India, Konnakol has journeyed across the globe, deeply influencing many artists. Today, musicians and dancers of varied backgrounds across the world, come forward to India to learn Konnakol, primarily to gain mastery, by exploring newer and exciting facets in rhythm. In simple, Konnakol is the most ancient and most modern art, which equally appeals to and attracts artists, aspirants, children, and the common man, with a massive fan following all over the world.

Konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally in Carnatic music. Carnatic music has a large oral tradition. Sollutkuttu refers to the mix of Konnakol and the beating of the hand to keep up the meter. Each tala (meter) can be recited vocally. Research shows that most Carnatic music follows a deep mathematical inner logic in melodic movements.

The mathematical elements of Carnatic music can be shown through how the time signature never changes during a piece. Talas may be added but it is on the same baseline time signature. When speed is increased it is always done in perfect multiples of the original beat. This becomes intriguing because it allows us to trace mathematical concepts within music.

A video by Konnakol and Mridangam musician B.C. Manjunath has become viral around the world. It shows how Konnakol can emulate the Fibonacci sequence. In mathematics, the Fibonacci numbers, commonly denoted Fn, form a sequence, called the Fibonacci sequence, such that each number is the sum of the two preceding ones, starting from 0 and 1. Fibonacci’s sequence is special because it is found everywhere, in art, architecture, design, trees, shells, hurricanes, galaxies, and of course in music. Manjunath uses the Konnakol to show the consistency of the sequence:

However, Konnakol is not just a musical art form, it also has deep roots in mathematics. In fact, Konnakol is often referred to as a "mathematical language" due to the close relationship between the rhythms in Konnakol and mathematical principles.

Konnakol shows much more complex mathematics. It uses mathematics to create complex polyrhythms, geometric patterns, and metric modulations. For example, Yati in Carnatic Music is expanding or decreasing syllabic patterns that, when written down, create a geometric shape. While music is often thought to be subjective, Carnatic music sets itself apart where every change in beat or rhythm can be mathematically traced.

In Konnakol, each rhythm is broken down into a sequence of syllables, with each syllable representing a specific note value or duration. For example, the syllable "ta" is often used to represent a quarter note, while the syllable "ki" might represent an eighth note. By combining these syllables in various patterns, Konnakol performers can create intricate and complex rhythms that are similar to those found in Western music.

But the relationship between Konnakol and mathematics goes even deeper than just the use of syllables to represent rhythms. The rhythms themselves are based on mathematical concepts such as prime numbers, Fibonacci sequences, and geometric patterns.

For example, one of the most basic rhythms in Konnakol is called the "tisra nadai," which is a rhythm with three beats per cycle. This rhythm is often represented using the syllables "ta-ki-ta," where "ta" represents a beat of one unit and "ki" represents a beat of half a unit. This simple rhythm forms the basis for many more complex rhythms in Konnakol.

Another important concept in Konnakol is the use of "korvais," which are rhythmic patterns that repeat over a cycle of beats. These korvais can be used to create complex rhythms that are based on mathematical principles such as prime numbers and geometric patterns.

In addition to its use in Carnatic music, Konnakol has also gained popularity in other genres of music such as jazz, fusion, and contemporary music. Many musicians have recognized the unique and complex rhythmic language of Konnakol and have incorporated it into their own music, creating a fusion of Indian and Western musical traditions.

Overall, Konnakol is a fascinating art form that highlights the close relationship between music and mathematics. Its use of syllables to represent rhythms, along with its incorporation of mathematical principles such as prime numbers and geometric patterns, makes it a unique and complex form of musical expression.

Let this percussionist blow your mind with the Fibonacci Sequence

Rhythm nerd alert! Bow down, drummers! Our social feeds have been on fire with a mind-bending, gasp-worthy video posted by percuss.io earlier this week — below — made by the accomplished Indian percussionist B.C. Manjunath. He's a master of konnakol -- the Carnatic, or South Indian, art of speaking percussive syllables in rapid-fire, intricate patterns to convey a larger thalam, or rhythmic cycle.

But here, B.C. Manjunath isn't using any old thalam for his whirl of konnakol — in an inspired stroke, he is using a Fibonacci sequence gorgeously, to take off into a dazzling, awe-inducing rhythmic fantasy.

(Math refresher! A Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers in which each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. Here, he uses the simple pattern of 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and 21. That is: 1 + 1 = 2; 2+1 = 3; 3 + 2 = 5; 5 +3 = 8; 8 + 5 = 13; 13 + 8 = 21. Got it? Good.)

So, in B.C. Manjunath's thalam, each of those Fibonacci segments makes up part of a larger rhythmic cycle. (You can get a closer look at what he's doing and follow along here, thanks to percuss.io's transcription and animation.) The result ... well, just hold on to your seat, and watch the whole video. It will make your day.

And if you can't get enough of Carnatic music and the Fibonacci numbers, check out this other mathematically inspired performance from composer and singer — and scientist — Venkata S. Viraraghavan, violinist Muruganandan Vasudevan and mridangam (drum) player Jagadeesh Janardhanan. It's a song in praise, appropriately enough, of the Hindu goddess Saraswati — the deity of both music and learning.

References:

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- How Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was establishing Hindu Samrajya by concluding centuries of Islamic oppression - Historian GB Mehandale destroys secular propaganda against Hindu Samrajya Divas

- Hindus documented massacres for 1000s of years: Incomplete but indicative History of Attacks on India from 636 AD

- ‘Kanyādāna’ in an Age of lunacy and trending social media campaigns: To Give or Not to Give

- Godse's speech and analysis of fanaticism of Gandhi: Hindus should never be angry against Muslims

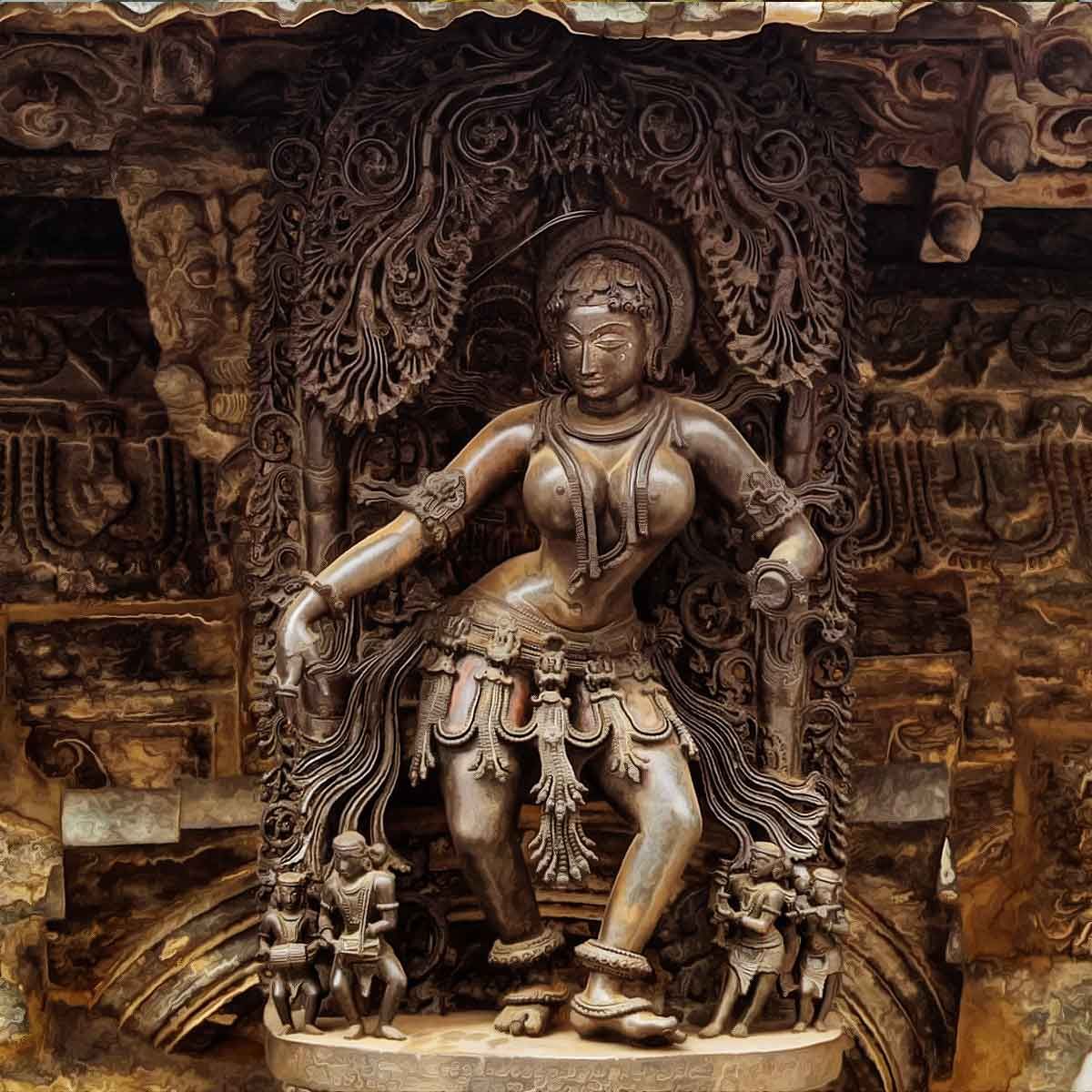

- "Words on a page can hypnotize you if the rhythm is right": “Kalinga narthana” literally means “Kalinga dance” in Sanskrit, referring to a legend in which Shri Krishna, as a young boy, danced on the serpent Kaliya to stop him from poisoning Yamuna river

- A new symbol of Hindutva pride, Shri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Corridor

- "Sanskrit is the language of philosophy, science, and religion": A Neuroscientist, James Hartzell explored the "Sanskrit Effect" and MRI scans proved that memorizing ancient mantras increases the size of brain regions associated with cognitive function

- Bhagwad Gita course for corporates is all set to launch at IIM Ahmedabad, will teach management and leadership

- "Embrace the light within and discover the boundless expanse of enlightenment": IIT Kanpur, renowned for its remarkable advancements in science and technology embarks on a sacred endeavor to digitize and disseminate Indian philosophical texts, and Vedas

- 21-yr-old girl Bina Das shot Bengal Governor in her convocation programme at Calcutta University, got Padma Shri but died in penury

- The Calculated Destruction of Indian Gurukuls (Education System) by British Raj which resulted in the tormented Indian Spirit

- A Different 9/11: How Vivekananda Won Americans’ Hearts and Minds

- The Balliol college at the University of Oxford has dedicated a new building after Dr. Lakshman Sarup, the first candidate at Oxford to pass his thesis for a Doctorate of Philosophy (DPhil) degree on Sanskrit treatise on etymology

- Dangers of losing our identity: Guru Tegh Bahadur forgotten and Aurangzeb being glorified

- Unsung Heroine Pritilata Waddedar, Who Shook The British Raj at the age of 21