More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

Milords, why demand to stand above criticism when democracy thrives on questioning, for Justice B Sudershan Reddy’s Salwa Judum verdict shows even judges must face accountability, no matter how powerful their robes once were

On 26th August, a group of retired judges issued a strongly worded response that has reignited the debate on judicial accountability. Their intervention came after some sitting judges and activists defended former Justice B. Sudershan Reddy from political criticism. The retired judges, however, plainly stated that judicial independence was not under threat from Amit Shah’s remarks.

Justice Reddy, who is now contesting as the Vice President candidate of the Opposition alliance, became the flashpoint of this controversy. The retired judges reminded their colleagues of a fundamental democratic principle: when a judge chooses to leave the bench and step into the electoral arena, he becomes “fair game for criticism.” Politics, by its nature, invites scrutiny. No candidate can be insulated from their past decisions, and former judges are no exception.

This counter-letter exposes the larger issue: why do some judges want to remain beyond criticism in a democracy? In a system where every public figure—be it a minister, bureaucrat, or journalist—is subjected to intense questioning, is it reasonable for judges turned politicians to demand immunity? Should citizens be silenced when they question the electoral ambitions of those whose past rulings changed the course of national security? Or should democracy thrive precisely on such criticism?

The intervention by retired judges underlines that criticism of judicial figures, once they enter politics, is not an attack on judicial independence but a rightful exercise of democratic freedom.

|

Amit Shah’s Attack: Linking Justice Reddy to the Salwa Judum Verdict

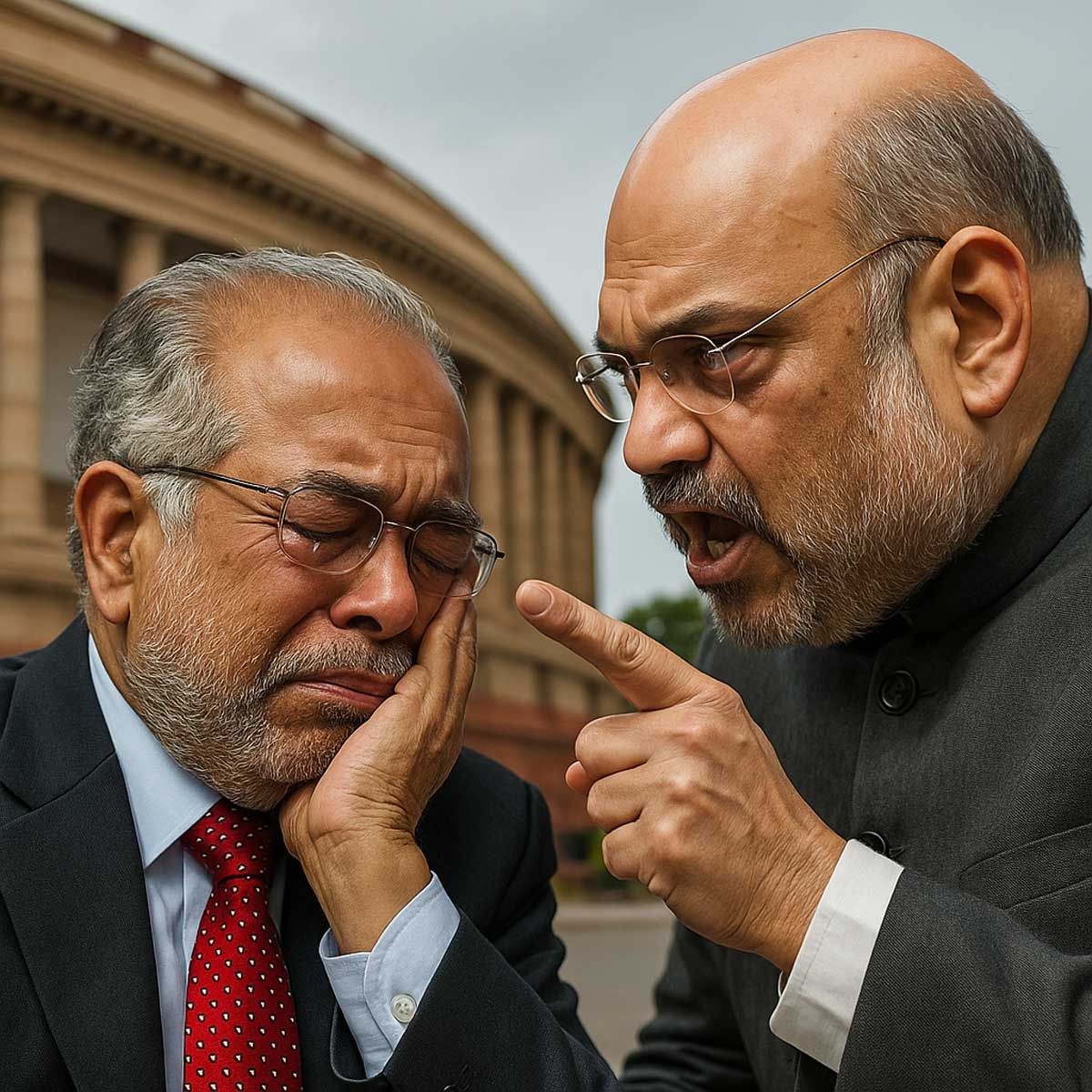

On 22nd August, Union Home Minister Amit Shah delivered a blunt political message at the Manorama News Conclave in Kochi, Kerala. Without hesitation, he accused the Congress party of succumbing to Leftist pressure by selecting Justice B. Sudershan Reddy as its Vice Presidential candidate.

Amit Shah connected this decision directly to Justice Reddy’s judicial past, specifically his role in disbanding the anti-Maoist civilian force in Chhattisgarh. He recalled the controversial 2011 Supreme Court judgment where Justices Reddy and SS Nijjar struck down the policy of arming tribal youth to fight Maoists.

In Shah’s own words: “The opposition (Congress) vice presidential candidate Sudarshan Reddy is the same person who gave the Salwa Judum judgment in support of leftist extremism and Naxalism. If this had not been done, extremism would have been eradicated by 2020.”

He reminded the people of Kerala that their own state had suffered from the sting of Naxalism and extremist violence. By fielding Justice Reddy, Shah argued, Congress had exposed its ideological tilt under Leftist influence.

This was not a generic rant against the judiciary. It was a calculated political critique against a rival candidate, targeting his record. In any healthy democracy, questioning a candidate’s track record is not just normal—it is necessary. The question that follows is: should Justice Reddy, now a politician, be shielded from such scrutiny? Or does he, like every other candidate, have to answer for his past actions?

|

The 2011 Salwa Judum Verdict: A Turning Point in the Naxal Debate

To understand the storm over Amit Shah’s remarks, it is necessary to revisit the Salwa Judum judgment of 2011. A Supreme Court bench led by Justices Reddy and Nijjar struck down the Chhattisgarh government’s decision to arm tribal youth as Special Police Officers (SPOs) to fight Maoists.

The case was brought forward through a petition filed by Nandini Sundar and other Left-leaning activists. The Court not only ordered the disbanding of the Salwa Judum, but also directed the state to recall all firearms and ensure that the youth involved were protected from Maoist reprisals.

The judgment went further. It ordered the state to investigate allegations of human rights abuses and other crimes committed by members of Salwa Judum or the Koya Commandos. The Court declared that no group could be permitted to operate outside the boundaries of the Constitution.

The bench observed: “The effectiveness of the force cannot be the sole criterion to judge whether it is constitutionally permissible.” It stressed that even if the SPOs were somewhat successful in tackling Maoists, the “dubious gains” had come at the unacceptable cost of constitutional violations and social instability.

For the state and the Centre, this was a major setback. Salwa Judum, despite criticism, had been one of the few active counter-strategies against Maoists in their strongholds. By disbanding it, the Court arguably left security forces vulnerable. This is why Amit Shah later argued that, had the judiciary not intervened, the war against Naxalism might have been over by 2020.

But here lies the dilemma: when judges step into the electoral field, are their past judgments immune to political debate? Can they campaign without accountability for decisions that altered the security landscape of the country? Or should voters be reminded of those decisions before casting their ballot? These are the democratic questions that the controversy has forced into the open.

When “Eminent” Judges Defend the Verdict

Just two days after Amit Shah’s statement, on 24th August, a set of retired judges and activists responded sharply. They sent a letter accusing Shah of “publicly misinterpreting” the Salwa Judum judgment, insisting that the verdict never supported Naxalism. They also urged that campaigns for high office should be conducted with dignity and without questioning ideology.

The signatories included well‑known former judges from India’s top courts — Madan Lokur, J. Chelameswar, Kurian Joseph, Abhay Oka, and A.K. Patnaik — along with former High Court judges and activists like Sanjay Hegde and Mohan Gopal. Their tone bordered on the pompous: how dare a political figure reinterpret a judicial verdict? They warned that Shah’s comments could create a “chilling effect” on the independence of the judiciary. In essence, they demanded immunity from critique, even though one of their own has entered the often messy world of politics.

|

Judges Who See Through the Act Push Back

But the defence didn’t go unchallenged. A larger group of retired judges, clearly unimpressed by that tone, issued a counter‑statement. They called out the pattern of some former judges using the guise of "judicial independence" to cloak political leanings.

They reminded everyone that once Justice Reddy decided to contest the Vice‑President’s election, he entered politics and must defend his record like any other candidate. They insisted that criticism of a political candidate — even if formerly a judge — isn’t an attack on judicial independence. The real harm, they argued, comes when retired judges repeatedly issue partisan political statements, creating the impression that the judiciary itself aligned with one political side.

One line cut straight to the heart: because of a few, the entire body of judges ends up painted as partisan. That, they emphasized, is harmful both for the judiciary and for democracy.

Criticism of Judges Is Not Contempt

Here’s the core issue: retired or sitting judges are not gods—they are human beings whose decisions affect millions. When a verdict changes the course of national security or civil liberties, it will draw public attention and debate. That is the essence of democracy.

Yet in India, there seems to be a silent belief among some judges that any criticism of their rulings is an attack on the Constitution itself. That is deeply anti-democratic. If ministers, bureau chiefs, generals, and journalists are open to public scrutiny, why should judges—especially those who enter politics—be exceptions?

Free speech doesn’t have a courtroom boundary. Democracy requires that judgments with far-reaching impact be discussed openly. Amit Shah’s remarks, while politically charged, were a legitimate commentary on how a past judicial ruling shaped the fight against Maoist insurgency.

Labeling such critique as “misinterpretation” or claiming it creates a “chilling effect” is like demanding a monopoly on interpretation—as if only the judiciary can explain its own words. It becomes especially hypocritical when retired judges sign statements that echo a single political bloc, yet turn around and decry criticism as partisan. That double standard is transparent to the public.

Democracy Means Accountability for All

This controversy isn’t just about Amit Shah and Justice Reddy. It raises a broader question: what is the role of the judiciary in a political democracy? Once judges step into the political field, they must accept that their records will be examined. Their judgments—especially those that shaped national security—will be scrutinized, their ideologies questioned. That’s not an assault on judicial independence, but rather a necessity of democratic accountability.

The judiciary deserves respect—but only so long as it remains above partisan politics. When retired judges act like political players, they lose the moral high ground to demand protection from criticism. Democracy demands that no institution or individual be beyond question.

So, to those who cry foul at any critique: a simple reminder — you are not gods, you are not above questioning, and this is not how a democracy works.

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- SC's interim order restraining mosque surveys under the Places of Worship Act sends a troubling signal, empowering mob veto and prioritizing 'harmony' over constitutional rights and judicial independence, raising serious concerns for democracy

- Supreme Court of India Justice Nagarathna ~ Hate Speech denies human beings the Right to Dignity, and a greater responsibility is cast upon public functionaries and celebrities against vitriolic statements owing to their position

- Shoe hurled at CJI BR Gavai in Supreme Court after his mocking remark on Lord Vishnu idol at Khajuraho ignites fury, wounding the faith of billions of Hindus worldwide

- Twitter rewards an Islamist org, set to be banned by India, with a verified blue tick: Here is what PFI has done in the past

- "He deserves to be thrown out": Supreme Court upholds dismissal of Lieutenant Samuel Kamalesan after he refused to enter a Gurudwara during a regimental parade, stressing discipline and leadership in the Indian Army for unity rising

- "A verbal contract isn't worth the paper it's written on": Google moves Supreme Court against National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) order upholding CCI's ₹1,337 crore penalty for abuse of dominant position within the Android ecosystem

- 5 lakh kg of temple jewellery has been melted so far, DMK government planning to melt even more

- Husband submitted that his wife living separately for 10 years, she implicated false 498-A IPC, in which he was acquitted, and prayed for divorce on ground of mental cruelty: Court concurred disputes not serious

- “Open category means open to all”: Supreme Court backs merit over caste as Justices Dipankar Datta and Augustine George Masih uphold Rajasthan High Court ruling that SC/ST/OBC candidates scoring above general cutoff must get open seats

- "अंधा कानून": Rajasthan High Court overturns a decades-old rape conviction, ruling that removing a minor’s innerwear and undressing oneself does not constitute an 'attempt to rape,' but rather 'outraging the modesty of a woman' under Section 354 IPC

- Tehelka News | In a ground-breaking verdict, the Delhi High Court slapped Tehelka, Tarun Tejpal, Aniruddha Bahal, Mathew Samuel with an order to pay ₹2 crore to Major General MS Ahluwalia following a 2001 sting operation that defamed the ex-Army officer

- "It is only the cynicism that is born of success that is penetrating and valid": A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court on Monday dismissed a petitions challenging the Central government's 2016 decision to demonetise currency notes of ₹1,000 and ₹500

- "Can omnibus orders be passed against demolitions": Supreme Court asks in Jamiat pleas challenging "Bulldozer" actions against anti-social elements in Uttar Pradesh and other states, refuses to pass interim orders, next hearing on Aug 10

- "Festivals are happy places, and you don't really want to enjoy them on your own": CJI, Supreme Court ~ "Why do we always want to portray that religious festivals are the time for riots; for example, there are no riots during Ganesh Puja in Maharashtra"

- "Justice for sale, affordability varies": In an escalating controversy, Udhayanidhi Stalin's fierce criticisms of Sanatana Dharma lead to public uproar & legal petitions, Supreme Court denies expedited hearing, ‘Won’t allow it, follow standard procedures’