More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

The Bengal Files shatters the delicate and sophisticated image of a peaceful society hiding under the fragile umbrella of secularism and selective silence

When a film finishes at a premiere, it is natural for the audience to clap in excitement, appreciating the art they have just witnessed. But what happens when instead of applause, you sit in complete silence, unable to join the cheerful crowd?

|

This was the unsettling experience after watching The Bengal Files. The film does not merely entertain or showcase cinematic skill; it compels you to reflect on the countless real lives damaged by the violent partition of Bharat. It also forces you to question why such a cruel episode of history was deliberately hidden by our Sarkari historians and erased from the collective memory by the Bengali intellectual class.

The troubling questions echo beyond the movie screen. Why did our leadership decide to suppress the horrible history of Partition? Why did Leftists and Secular historians try to whitewash this chapter? Does applying band-aid to a deep wound cure the wound or lets it fester and turn into a gangrene? These are not simply rhetorical questions. They represent the dialogue of a young officer in the film who boldly asks his superior why every crime and social problem is ultimately reduced to a Hindu-Muslim issue. The dialogue mirrors the frustrations of many who wonder why painful truths are brushed aside in the name of harmony.

|

From a cinematic perspective, The Bengal Files stands apart with a screenplay even more engaging than The Kashmir Files. The decision to carry forward the protagonist from the earlier film is nothing less than a masterstroke. It creates narrative continuity and sends a strong message: the story of Bharat’s suffering did not stop with one region. Day before yesterday it was the Partition of Bharat, yesterday it was Kashmir, and today it is Bengal—all tied together by the common thread of religious extremism that continues to erupt as repeated horrors rather than isolated tragedies.

The storyline moves between two timelines—first, the tense and bloody months leading to August 15, 1947, and second, the modern-day political environment of Bengal shaped by minority-driven politics. The character of Bharati Banerjee, hauntingly portrayed by Pallavi Joshi, binds both worlds together. Her performance is deeply stirring and unforgettable. By the end of the film, it becomes clear that Bharati is more than just a character; she symbolizes Bharatmata herself, carrying the trauma of Partition and its recurring wounds.

|

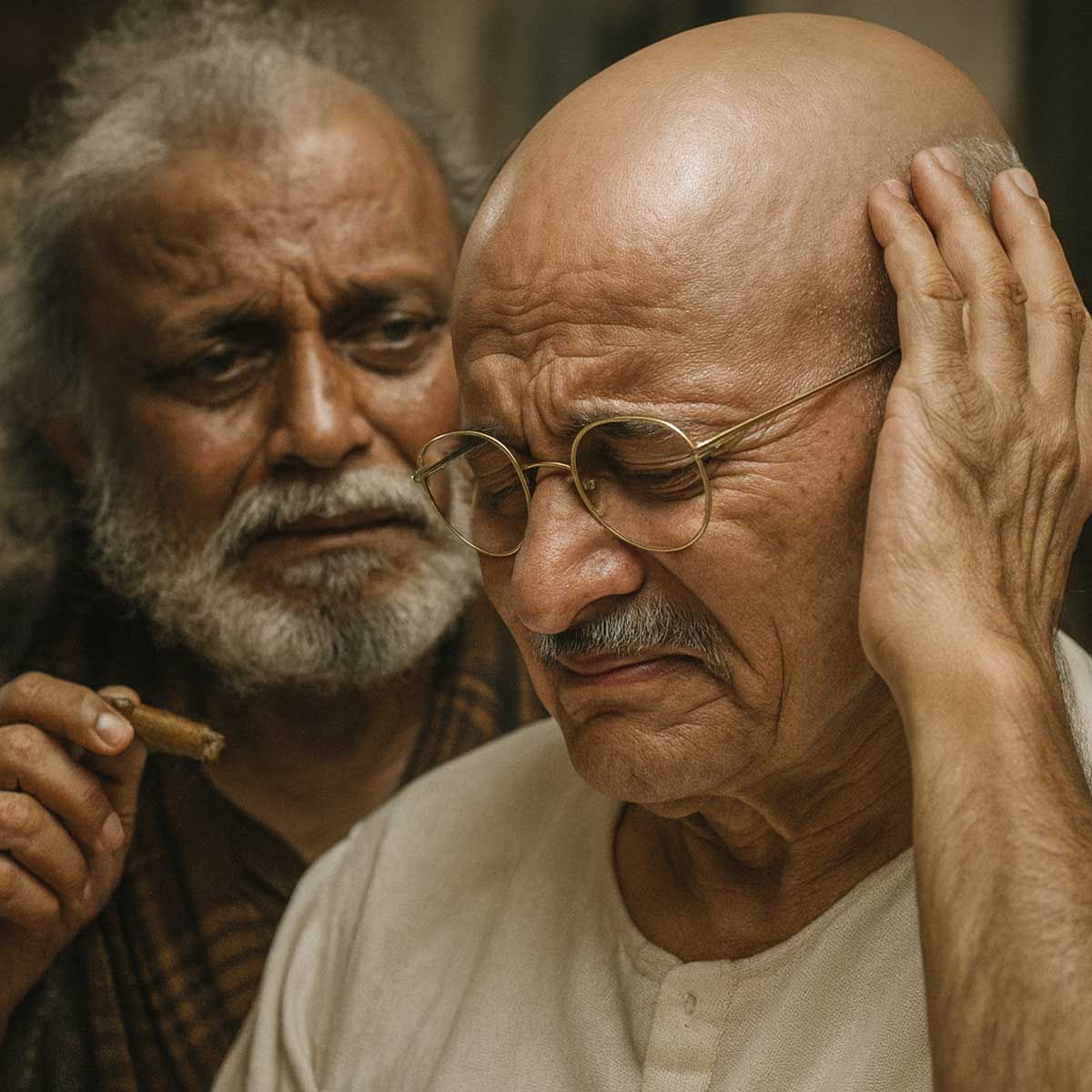

Another powerful element of the film is how it revives forgotten names and events. The courage of Gopal Patha and freedom fighters of the Hindu Mahasabha are finally acknowledged on screen—names unknown to most people. The film also portrays Gandhi ji as a man overwhelmed in the chaos of Kolkata and Noakhali, appearing confused and offering ‘benign advice’ to the women of Bengal who were being kidnapped and raped. Alongside, the film does not shy away from showing Congress leaders, who, weary and desperate for an early declaration of independence, accepted Partition even if it meant dividing a thousand-year-old civilization. The frightened and divided response of the Hindu community in 1946 adds another layer of discomfort. Reading about such incidents in books is one thing, but watching them visually recreated on screen makes the brutality real and unforgettable. Many of our grandparents and great-grandparents lived through those horrors but chose never to tell their stories.

|

The film is packed with hard-hitting dialogues, some of which have the potential to become iconic. Just like the famous line from The Kashmir Files—“Sarkar unki hai, par system hamara hai”—The Bengal Files delivers equally direct and unapologetic words about Hindu-Muslim relations and the false image of harmony built on ‘Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb’. These dialogues touch raw nerves, especially in a society where people fidget uncomfortably when these issues are raised. Yet the film insists that truth cannot be hidden behind nervous silence. Predictably, those who benefit from vote-bank politics will call for banning the film, while secular leaders of Bengal will continue repeating the weak argument: “Don’t watch it if you don’t like it.” Their silence when confronted with uncomfortable truths only exposes their dead conscience.

|

The casting of the film is another challenge that the director Vivek Agnihotri overcomes with precision. Stories like this are difficult to tell, yet he brings together a bold mix of seasoned actors and new faces. This creates authenticity, allowing viewers to see real characters rather than actors. Darshan Kumar, as Krishna Pandit, delivers monologues filled with frustration, impotent rage, and a lifetime of injustice, finally breaking free of “ghulami.” His performance stands as one of the highlights of the film. Mithun Chakraborty, Anupam Kher, Rajesh Khera, Namashi Chakraborty, Saswata Chatterjee, and others deliver impactful performances, each adding unique depth to their roles. Simratt Kaur, portraying young Bharati Mukerjee, shines in one of the most difficult roles. She embodies innocence and suffering so convincingly that viewers cannot help but empathize with her journey.

The film’s technical quality also adds to its power. The background score lingers long after the credits, and the careful use of well-known Bangla songs stirs deep emotion. Massive sets recreate the period atmosphere with accuracy, while the cinematography captures the raw brutality and the haunting silences of the past.

|

Ultimately, The Bengal Files forces its audience to confront their own illusions. This movie shatters your delicate sophisticated self-image of a peaceful society living under the umbrella of benign secularism, and ahimsa, and your assumptions. The film is not comfortable to watch, and that discomfort is deliberate. Unless history is faced with honesty and solutions are built on trust and truth, the same mistakes will repeat—whether as farce or tragedy. Across the world, communities have grown stronger by acknowledging painful histories. Holocaust films did not spark riots; they led to reflection and healing. In America, facing the crimes against Blacks and Natives has brought awareness, not peace by denial. In the same way, Agnihotri’s film seeks catharsis, not conflict. It reminds us that we must blame not the filmmaker, but the false narratives that have blinded us.

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Set of 'Ashram3' series ransacked by Bajrang Dal Activists, Throw ink at producer Prakash Jha's face

- Uphaar Cinema fire was one of the worst fire tragedies in recent Indian history: Association of Victims of Uphaar Fire Tragedy (AVUT) filed a landmark case considered a breakthrough in civil compensation law in India

- Legendary singer Zubeen Garg, 52, dies in a tragic scuba diving accident in Singapore during North East India Festival, leaving Assam, Bollywood and millions in grief

- From she is bipolar, had staged her attack to Karan was used to hitting her: Here’s what we know so far about the Karan Mehra-Nisha Rawal case

- Bollywood 'Shocked', 'Angry' After Court Rejects Aryan Khan's Bail

- Veteran actor Dilip Kumar passes away at 98

- Scripted praise, planned fights: Reports say controversies in Indian Idol are faked to boost TRP after Kishore Kumar episode sparks row

- "ओ, जानेवाले, हो सके तो लौट के आना, ये घाट, तू ये बाट कहीं भूल ना जाना": Comedian Raju Srivastava, who was admitted to AIIMS in New Delhi after he suffered heart attack, passed away, the world is a little sadder today and lost a part of its wit and humour

- Old clip where SRK said he’d be okay with his son doing drugs makes round after Aryan Khan detained in drugs party case

- Comparing Holi with terrorism and reducing Navratri to ‘mating dance’ — how the Indian media has turned Hinduphobic

- Indian movies have become propaganda platform to distort real incidents and perpetuate lies

- Kanyadan fame Celeb Tutor Alia Bhatt married Ranbir Kapoor in white, merrily cutting cakes, sipping champagne, and taking only four pheras despite having a Hindu Punjabi ceremony: Woke activists distorting Sanatan Dharma

- "When you’re in hell, only a devil can point the way out - #BoycottBollywood": Bollywood having lost its charm continues to push its agenda and the anti-Hindu narrative resulting in 75% of the films tanking in the last 6 months and facing inevitable doom

- Ranveer Singh and Jacqueline Fernandez among 28 Instagram influencers found in violation of ASCI guidelines: Details

- Formula for commercial success slipped away from Bollywood’s grip, masses started disconnecting with Karan Joharesque Punjabi prism: Success of South Indian cinema is churning wheels