More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

If not for Muslim appeasement, Vande Mataram would have been India's National Anthem: the history of Muslim opposition and support

In 2017, India’s national song Vande Mataram was mired in debate once again. Following the Madras High Court’s order to make Vande Mataram compulsory in schools and government and private offices, a loathsome politics was triggered over the national song in Maharashtra.

Citing the Madras High Court Order, BJP MLA Raj Purohit said that the singing of the national song should be made mandatory in schools and colleges across Maharashtra. This proposal, however, was strongly objected by MLAs from AIMIM and Samajwadi Party who called the song “anti-Islam”. MIM MLA Waris Pathan said he won’t sing Vande Mataram even if “someone puts a revolver to his head”. SP MLA and party’s Maharashtra unit president Abu Asim Azmi said he won’t sing the national song even if he is “thrown out of the country”.

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee - Man Who Wrote Vande Mataram |

Months ago a similar politics was witnessed over the national song when Municipal Corporations of Meerut, Moradabad, Varanasi and Gorakhpur had made the singing of Vande Mataram mandatory at the civic meetings. Muslim members belonging to Congress, SP and BSP had registered their protests.

Ahead of the centenary celebration of the national song in 2006, Islamic seminary Darul Uloom had issued a fatwa describing Vande Mataram as “anti-Islamic”. In 2009, Jamiat had issued another fatwa against the national song.

In 2013, the then BSP MP Shafiqur Rahman had walked out of the Lok Sabha when Vande Mataram was being sung.

These are some recent incidents, but the opposition to Vande Mataram dates back to the pre-independence era.

When Muslim League opposed Vande Mataram

The separatist agenda of Muslim League had opposed Vande Mataram. The year was 1909. Speaking at the second national session of Muslim League in Amritsar, the then party president Syed Ali Imam had termed Vande Mataram a “sectarian cry” while decrying the festival of Raksha Bandhan as “sectarian” in the same breath.

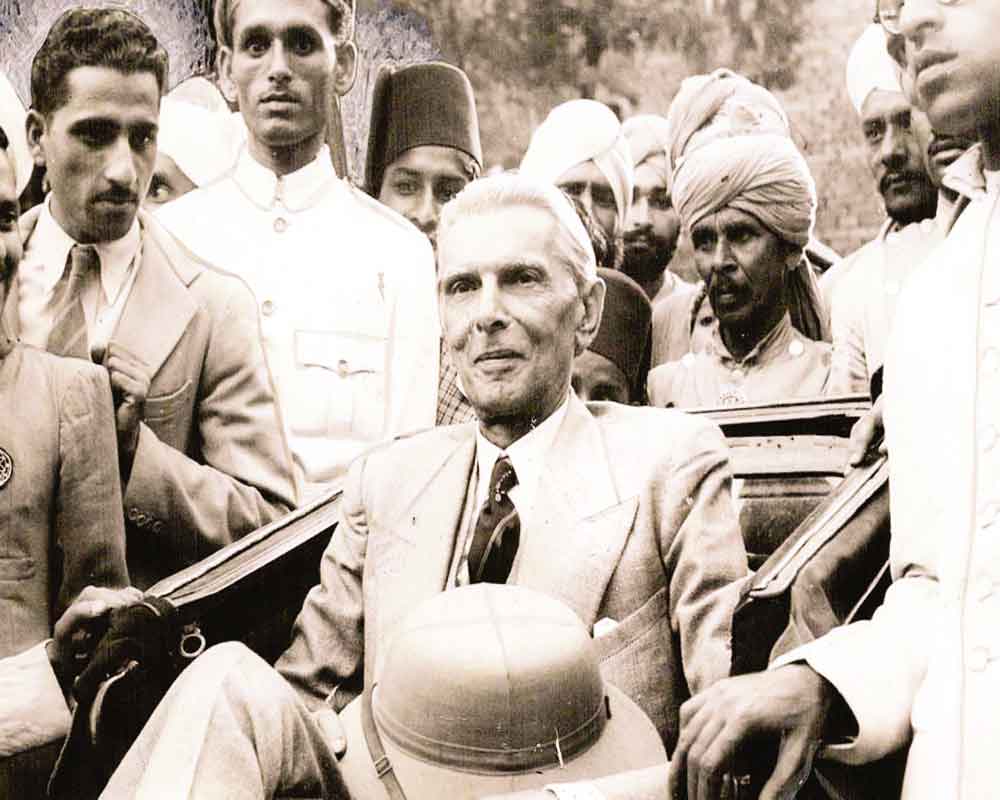

Three decades later, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who partitioned the country on religion lines, echoed similar views in an article dated 1 March, 1938, published in The New Times of Lahore:

“Muslims all over India have refused to accept Vande Mataram or any expurgated edition of the anti-Muslim song as a binding national anthem.”

To set the record straight, the issue of compulsion was settled about 70 years ago, during 1937-39. Mohammed Ali Jinnah purportedly gave vent to the anxiety of the Muslim community, that its members would be compelled to sing Vande Mataram. At a time when the nationalist leadership or the Indian National Congress did not have much power to compel, how genuine this anxiety was is a matter of debate. However, Jinnah put this point at the top of his agenda in his talks with Jawaharlal Nehru; among the Quaid-e-Azam papers, now in Pakistan, his discussion notes of February 1, 1938, bear this out: Vande Mataram must go.

On April 16, 1938, in his presidential address at the special session of the All India Muslim League in Calcutta, he focussed attention on the charge that the Indian National Congress endeavoured to impose the Vande Mataram song in the legislatures. In his presidential address at the Sind Provincial Muslim League Conference, Jinnah reiterated the charge as indeed he did on many other occasions.

Quaid-e-Azam MA Jinnah |

While one must acknowledge the build-up of considerable opposition to a song thus targeted by Jinnah, one must not forget the other side of the story. Although Vande Mataram, as a song and as a slogan, had been a part of the freedom struggle since the Swadeshi movement of 1905, there were doubts in Congress circles about its acceptability as a whole. The expurgated edition of the song, which Jinnah refers to in his article, was the outcome of these doubts.

A part of the song was indeed dropped by the Congress from the officially accepted version, by a resolution of the Congress Working Committee in October 1937.

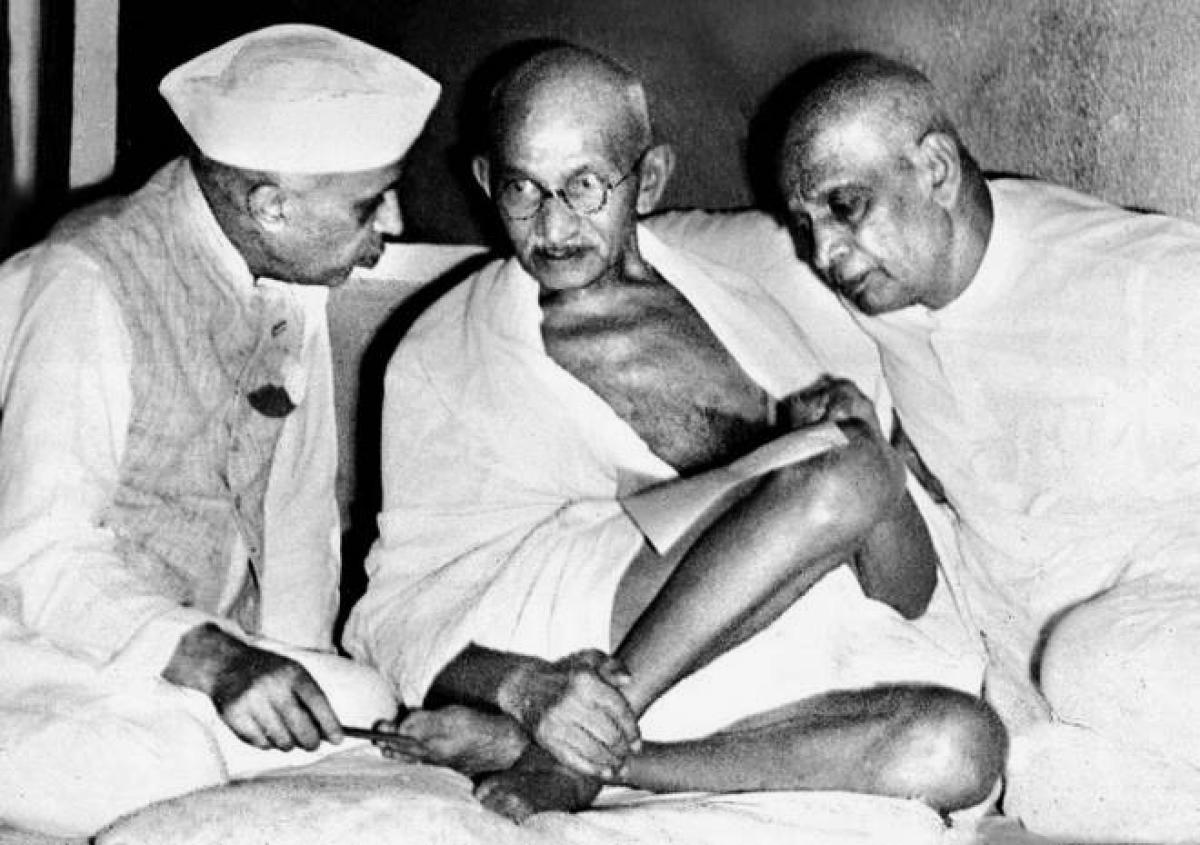

This was the part against which Muslim sentiment was strong. Further, the Congress addressed the issue of compulsion with a series of steps leading to the resolution drafted by Mahatma Gandhi himself in January 1939. The resolution was of vital importance in guiding the party as well as, in the long run, the Constituent Assembly in its decision to designate Vande Mataram as the national song, while Jana-gana-mana was given the status of the national anthem. It is evident from the draft resolution that Gandhi wrote with great caution and circumspection, and he wrote on top: Strictly Confidential: Not for Publication.

The resolution said: As to the singing of the long established national song, Vande Mataram, the Congress, anticipating objections, has retained as national song only those stanzas to which no objection could be taken on religious and other grounds. But except at purely Congress gatherings it should be left open to individuals whether they will stand up when the stanzas are sung. In the present state of things, in Local Board and Assembly meetings, which their members are obliged to attend, the singing of Vande Mataram should be discontinued.

There were some dissenting voices in the Congress. C. Rajagopalachari thought that such a concession will not save the situation (Rajagopalachari to Sardar Vallabbhai Patel, January 7, 1939), and even G.B. Pant was quite lukewarm about the idea (Pant to Nehru, January 8, 1939). Nevertheless, Gandhi and, by and large, the top leadership of the Congress regarded the measure as essential. The main idea was to decisively remove any apprehension of compulsion. It was nevertheless a decision that went against the grain of Gandhis cast of mind, and he wrote a sort of apologia in Harijan (July 1, 1939): now we have fallen on evil days. I will not risk a single quarrel over singing Vande Mataram at a mixed gathering. It will never suffer from disuse. It is enthroned in the hearts of millions.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and C. Rajagopalachari at the Government House |

Of these two policy decisions, that of October 1937 on expurgating the song and that of January 1939 recognising freedom from any compulsory participation in events where the song was sung, the first one caused agonising moments to the national leaders for it was the first time that they faced the task of reappraisal of a song sanctified by its historical associations. Thereby hangs a tale, which has as its protagonists not only Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, Subhas Chandra Bose and others in political decision-making but also Rabindranath Tagore.

Nehru was one of those Congress members who were not familiar with the song in fact as late as October 20, 1937, he wrote, I do not understand it without the help of a dictionary, but he had managed to get an English translation. He read for the first time Bankim Chandra Chatterjees novel in which the song features only six days before the Working Committee meeting to decide the fate of the song. There were others among his peers who had a strong attachment to it. Congress members noted that Vallabbhai Patel and Rajendra Prasad concluded their address as Congress presidents, in 1931 and 1934, with the Vande Mataram slogan; Nehru did not in 1929 and 1936. Thus, there was a difference in attitude within the leadership.

Dropping any part of the song was not an easy task. (The same difference probably persisted until the Constituent Assembly passed its resolution making Jana-gana-mana, not Vande Mataram, the national anthem. Since it was moved from the Chair by Rajendra Prasad, it was neither discussed nor put to vote and that conveniently put a stop to the controversy on the songs status.)

The problem due to differences within Congress was exacerbated by two factors. The Hindu Mahasabha organised a Vanda Mataram day in Pune and Bombay in October 1937, and elsewhere on other occasions, the party spokesmen began to urge the adoption of that song as the national anthem. Subhas Chandra Bose, in the meanwhile, was up in arms in favour of Vande Mataram. Nehrus response to him was that considering that there was an outcry against the song and people who have been communistically inclined were watching the Congress actions in this regard, the Congress must meet real grievances where they exist, without pandering to communalism (Nehru to Bose, October 20, 1937).

Nehru sought a way out of the situation by appealing to Tagore, who delivered a judgment that ultimately decided the issue for the Congress. Tagores reply was complex since he squarely faced the dilemma of reconciling loyalty to literary sensibility with political expediency.

|

The basic advice he offered was as follows: The first two stanzas of the song were unexceptionable. As regards the rest of the song, there could be objections from those with monotheistic ideals, and these stanzas could be dissociated from the first two. His advice was that while the song taken as a whole might wound Muslim susceptibilities, delinked from the rest of the lyric the first two stanzas might be accepted since they appeal to everyone on account of the spirit of tenderness and devotion expressed.

In his letter to Nehru (October 26, 1937), Tagore also mentioned that he was the first person to sing it at a session of the Indian National Congress, presumably the session in 1896 in Calcutta.

Recent research has established that Vande Mataram was indeed written in two distinctly different parts, and at different times. When Bankim Chandra wrote the first two stanzas sometime around 1872, it was just a beautiful hymn, the classical vandana in Sanskrit, to the motherland, richly watered, richly fruited, dark with the crops of the harvest, sweet of laughter, sweet of speech, the giver of bliss.

For several years, these first two stanzas remained unpublished. In 1881, this poem was included by Bankim Chandra in the novel Anandamath, and then it was expanded to endow the motherland with militant religious symbolism as the context of the narrative demanded. There now emerged a new icon of the motherland, terrible with the clamour of seventy million throats, likened to Durga holding ten weapons of war. The first two stanzas and the later stanzas belong to two different strata of Bankim Chandras literary life. Thus, the two parts of the song can be justifiably separated. However, when the decision was made to drop the latter part of the song, these facts were not known to the decision-makers.

On the lines of Tagores advice, the Congress Working Committee passed the resolution mentioned earlier. The committee recognises the validity of the objection raised by Muslim friends to certain parts of the song. The committee accepted only the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram and not the other stanzas.

Most important was the degree of freedom conceded in the resolution: The committee recommends that wherever Vande Mataram is sung at national gatherings only the first two stanzas should be sung, with perfect freedom to the organisers to sing any other song of an unobjectionable character, in addition to, or in the place of, the Vande Mataram song.

The attempts to eliminate the element of compulsion are beyond question, but that did not satisfy the songs opponents. Jinnah continued with his tirades. The political appropriation or conspicuous rejection of cultural symbols and artefacts was part of the identity assertion that a political agenda demanded. There were a number of Muslim intellectuals and public spokespersons who accepted the song, specially the amended version that the Congress adopted. Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, for instance, considered the attitude of Jinnah as only a subterfuge. He pointed out that for years the song was sung at the beginning of Congress sessions and no objections were raised by Muslim members including Jinnah (Kidwais press statement, The Pioneer, October 19, 1937).

Likewise, Dr Syed Mahmood of the Bihar Legislative Assembly or Professor Reza-ul Karim in Bengal were not persuaded by Jinnahs arguments about the song. At the same time, there was undoubtedly a widely shared discomfort with the song in Muslim political circles in these provinces as well as Sind, Madras and Bombay. Jinnah gave voice to it stridently, but it was not entirely his creation.

What is the controversy about

Vande Mataram, which means “I praise thee Mother” or “I bow to thee Mother”, is an ode to Mother India. The song envisions all citizens as its children. Because the song is an ode to Mother India, some Muslim politicians and maulvis – who claim to represent the Muslim voice – argue that singing of Vande Mataram is against the “tenets of Islam” and a “sacrilege against Allah” because a Muslim can bow to only Allah and no one else.

This opposition is more about political muscle flexing — unfortunately supported by so-called secular politicians — than religious beliefs, because many Muslim politicians and scholars have supported the song.

|

Muslims support Vande Mataram

Well known Muslim scholar and noted freedom fighter Maulana Abul Kalam Azad saw a “fusion of endogenic creativity”, Islamic doctrines of “Wahdat-e-Deen” (Unity of religion) and “Sulah-e-Kul” (Universal peace) in Vande Mataram. Pertinent to mention that when Azad was the Congress president, Vande Mataram was sung in each and every session of the party.

Rafi Ahmad Kidwai, a prominent Muslim leader who worked as the Minister for Communications in Jawaharlal Nehru Cabinet, had also strongly defended Vande Mataram.

Author and activist Arif Mohammed Khan, who was also a long-time Member of the Parliament, had translated Vande Mataram in Urdu. In a 2006 article in Outlook, Khan wrote:

“The opposition to Vande Mataram came from the Muslim League, which under the leadership of Mohammad Ali Jinnah had developed a different attitude from those of nationalists on the question of India’s freedom from foreign rule.

I have no doubt that opposition to Vande Mataram is not rooted in religion but in divisive politics that led to Partition.

Those who persist in their opposition are actually negating a constitutional ideal. After all, the Constitution is not merely an exercise in semantics but expression of the people’s national faith.”

Tearing into the blabber that “Vande Mataram is anti-Islamic”, Khan said:

“From the Islamic viewpoint, the basic yardstick of an action is Innamal Aamalu Binnyat (action depends on intention). Hailing or saluting Motherland or singing its beauty and beneficence is not sajda.”

Noted educationist Firoz Bakht Ahmed wrote in a 2006 article in The Pioneer:

“The melody, the thought content and the ambience of patriotism of Vande Mataram is unmatchable. It is high time that the so-called Muslim leaders stopped politicising the issue of Vande Mataram to promote their mucky politics.

As a Muslim, I would like to convey a message to all my countrymen and especially my own community that some politically motivated people are trying to make an emotive issue out of Vande Mataram, a gem of a song and perhaps the song that in my view should have been the national anthem in place of Jana gana mana…”

And of course, music maestro AR Rahman, through his music album Ma Tujhe Salam, gave Vande Mataram a new dimension.

Vande Mataram – A brief history

It is important to revisit the history of Vande Mataram and understand its relevance in order to get the right perspective. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee penned the evocative song in 1870s, which he later included in his novel Anandmath published in 1882.

Sri Aurobindo called Vande Mataram as the mantra of the “new religion of patriotism”. Soon the song emerged as a hymn for Indian Independence Movement. From Mahatma Gandhi to Shubhash Chandra Bose, Vande Mataram was a mantra in the struggle for India’s independence.

Mahatma Gandhi associated the song with the “purest national spirit”. In an article dated 1 July, 1939, published in Harijan journal, Gandhi wrote:

“It was an anti-imperialist cry. As a lad, when I knew nothing of Anandamath or even Bankim, its immortal author, Vande Mataram had gripped me, and when I first heard it sung it had enthralled me. I associated the purest national spirit with it. It never occurred to me that it was a Hindu song or meant only for Hindus… It stirs to its depth the patriotism of millions. Its chosen stanzas are Bengal’s gift among many others to the whole nation.”

Pre-independence Indian society left no stones unturned in its endeavours to make Vande Mataram into a national slogan, reaching as far as England.

In the book Glorious thoughts of Tagore, a chapter called ‘Sandip’s Story’ has a very beautiful connotation on Vande Mataram. Referring to the protagonist of the story, Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

“Vande Mataram! These are the magic words which will open the door of his iron safe, break through the walls of his strong room, and confound the hearts of those who are disloyal to its call to say Vande Mataram.”

It was Congress which adopted Vande Mataram as the national song at its Varanasi Session on 7 September, 1905. On the first such political occasion, it was Rabindranath Tagore who sang Vande Mataram at 1896 Congress Session in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Five years later, Dakhina Charan Sen sang it in another session of Congress at Kolkata.

Lala Lajpat Rai started an Urdu weekly in the name of Vande Mataram from Lahore. Bipin Chandra Pal had founded a newspaper called Bande Mataram in 1905, which was later edited by Sri Aurobindo. An editorial in the newspaper exhorted:

“In every village, every town Anandamath must be established. Then the Mother’s name will be uttered by crores of throats and every side will resound Vande Mataram.”

In 1907, Bhikaiji Cama unfurled the first version of India’s national flag at Stuttgart, Germany with Vande Mataram written on its middle band. Matangini Hazra’s last words, as she was shot to death by the British Police, were Vande Mataram.

In Independent India, the first two stanzas of the song was declared as the national song by the Constituent Assembly on 24 January, 1950. While presiding over the Constituent Assembly, Dr Rajendra Prasad – the first President of India – had said:

“…The song Vande Mataram, which has played a historic part in the struggle for Indian freedom, shall be honoured equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it.”

While making a statement to the Legislative Committee of the Constituent Assembly on August 25, 1948, first Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru had said:

“Vande Mataram is obviously and indisputably the premier national song of India, with a great historical tradition, and intimately connected with our struggle for freedom. That position it is bound to retain and no other song can displace it. It represents the position and poignancy of that struggle, but perhaps not so much the culmination of it.”

|

Postscript

The history of Vande Mataram clearly shows that it is actually the opposition to the song that is sectarian and not the song itself. Those who espoused opposition to the song finally ended up demanding a separate nation for Muslims in Pakistan. Unfortunately, the same demand today passes off as “secularism”.

Today, when there are reassertions of old charges and re-enactments of old battles, it is encouraging to see how many Muslim intellectuals and public persons have reacted. Of the many enlightened reactions, perhaps, the most delightful for its directness is that of the poet Javed Akhtar. He reportedly said: What is this new resistance? The objection is redundant. You dont want to sing Vande Mataram, dont. Who is forcing you? I sing it. I dont see it as objectionable. If you do, dont sing it.

However, perhaps there is an inadequacy and a probably widespread intellectual tendency to say that at the root of it there is ignorance about the battles that are over. It is not enough to say that. What makes uninformed conceptions acceptable to a number of people? It is not enough to say that the misconception originated among a section of clerics; some of them may be plebeians among the intellectuals, but there are also intellectuals among the plebeians. They exercise great influence and merit attention.

And finally, if there is a generalised perception of a threat to cultural identity, even if it is based on wrong premises, it needs to be studied and addressed. In these few pages an attempt has been made to put the record straight in terms of history, but one has to think of tasks beyond that.

वन्दे मातरम्, वन्दे मातरम्

सुजलां सुफलां मलयजशीतलाम्

शस्यशामलां मातरम्

वन्दे मातरम्

शुभ्रज्योत्स्नापुलकितयामिनीं

फुल्लकुसुमित द्रुमदलशोभिनीं

सुहासिनीं सुमधुर भाषिणीं

सुखदां वरदां मातरम्

वन्दे मातरम्, वन्दे मातरम्

कोटि कोटि कण्ठ कल कल निनाद कराले

कोटि कोटि भुजैर्धृत खरकरवाले

अबला केन मा एत बले

बहुबलधारिणीं नमामि तारिणीं

रिपुदलवारिणीं मातरम् वन्दे मातरम्

तुमि विद्या तुमि धर्म तुमि हृदि

तुमि मर्म त्वं हि प्राणा:

शरीरे बाहुते तुमि मा शक्ति

हृदये तुमि मा भक्ति

तोमारई प्रतिमा गडि मन्दिरे-मन्दिरे मातरम्

वन्दे मातरम्

त्वं हि दुर्गा दशप्रहरणधारिणी

कमला कमलदलविहारिणी वाणी विद्यादायिनी

नमामि त्वाम् नमामि कमलां

अमलां अतुलां सुजलां सुफलां मातरम्

वन्दे मातरम्

श्यामलां सरलां सुस्मितां

भूषितां धरणीं भरणीं मातरम्

वन्दे मातरम्, वन्दे मातरम्

References:

frontline.thehindu.com - Sabyasachi Bhattacharya

opindia.com - Saswat Panigrahi

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Godse's speech and analysis of fanaticism of Gandhi: Hindus should never be angry against Muslims

- Narasimha Rao govt brought places of Worship Act as a hurdle in reclaiming ancient Hindu heritage destroyed by Muslim invaders

- An Artisan Heritage Crafts Village: Indigenous Sustainability of Raghurajpur

- Massive endorsement of anti-Grooming Jihad laws: Here are the takeaways from the Kashmir controversy and how Khalistanis swallowed a bitter pill

- Indian state bans book on Mahatama Gandhi after reviews hint at his gay relationship

- If only India’s partition chilling wound was not enough, Gandhi did his last protest again only to blackmail India into giving 55 crores to Pakistan, dragged Hindu, Sikh refugees seeking shelter in mosques to die in cold: And we call him Mahatma, not for

- The ‘Sanghi propaganda’ trope on abduction and conversion of Sikh girls to Islam. Here is how this online tirade is an omen of impending danger

- Violent mob throwing stones, and radicals chopping off limbs is okay for ‘Liberals’ but a Hindu tweeting dislike for an ad is dangerous

- Aurangzeb banned Diwali 350 years ago, Courts and governments are just following Mughal ruler

- Twitter rewards an Islamist org, set to be banned by India, with a verified blue tick: Here is what PFI has done in the past

- Shoaib Akhtar endorses AMU founder’s two-nation theory that caused partition: Not some stupid comment but a statement of fact

- Why India’s temples must be freed from government control

- Tragedy or Drama: Mufti Mohammad Sayeed's daughter Rubaiya abduction led to free five most notorious terrorists

- Indonesia: Sukmawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of Indonesia's first president becomes a Hindu leaving Islam

- ‘State in denial, admin lied about no complaints being filed, prima facie evidence of violence’: Everything Calcutta HC said on Bengal post-poll violence