More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

An Artisan Heritage Crafts Village: Indigenous Sustainability of Raghurajpur

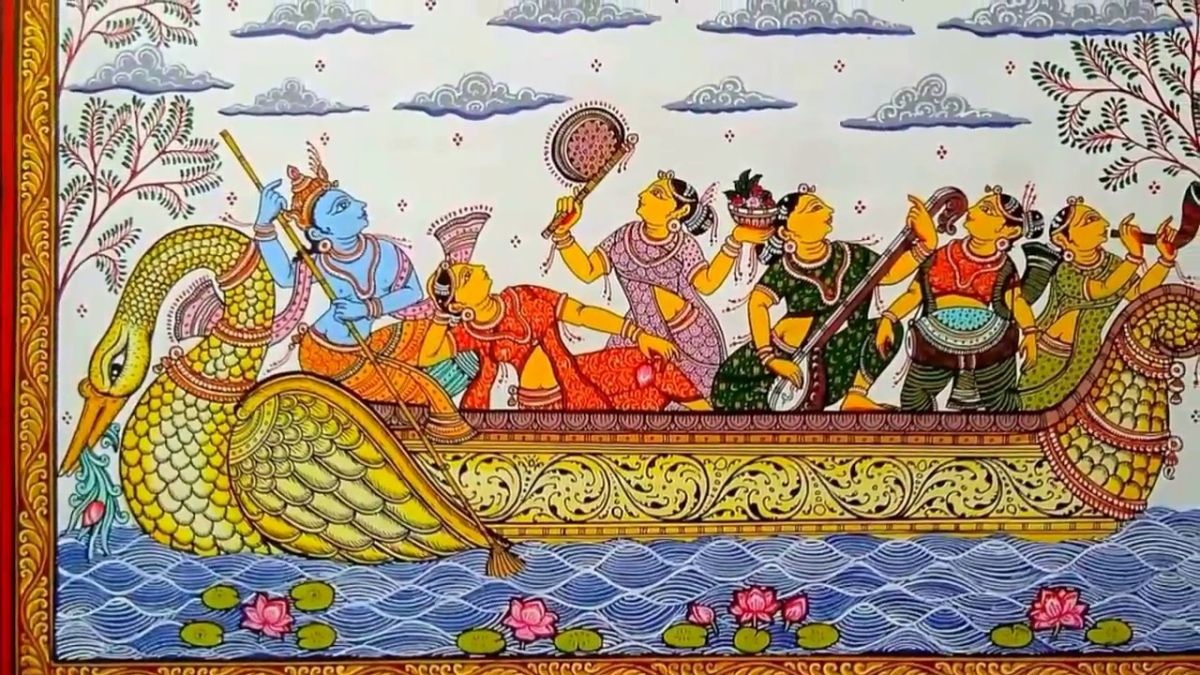

Raghurajpur is a heritage crafts village in the district of Puri in the state of Odisha. This village is recognized for its folk art called Pattachitra, an art form which dates back to 5th Century B.C. and Gotipua dance which existed as a predecessor before the emergence of Odissi dance and is hence the home of a prominent visual art as well as a performing art.

The artisans of this village are also engaged in crafting various other craft objects like wooden toys and masks, palm leaf engravings, wood carvings, etc. These activities have provided them income opportunities outside their state and even in foreign lands. The master dancer Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, belonging to this village, is the person responsible for the popularity of the Odissi dance form today.

The village was given the status of heritage village, the first in the state, by INTACH in the year 2000. Though the state government has attempted to improve the physical conditions so as to make them tourist friendly but the impacts of these interventions have been minimal. The traditions of the residents make it an open air museum for the outsiders but a home for the residents. These practices are also the very essence of sustainability, a trend catching up throughout the world, as seen from the raw materials used in the painting process, in the colours, canvases, etc. and the manner in which the painting is done. This is an example of the complex relationship which the village shares with the environment and is exclusive to the place, making it an important focus of rural tourism in the state.

Raghunath, a resident of Odisha’s Raghurajpur village, is a fourth generation artist engaged in Pattachitra, a cloth-based scroll painting. This art form dates back to the 12th century. In the last 22 years, the artist has created hundreds of these intricate paintings.

What makes Raghunath’s paintings stand out is that he makes organic colours from seashells, flowers and leaves to make sharp, angular and bold lines to depict epics, gods and goddesses.

In fact, he is one of the many artists keeping alive this art in his village, which is a hub of the indigenous art form, with at least one artist involved in the trade in every family.

However, the coronavirus-induced pandemic has severely affected his sales ever since March 2020. So instead of colouring on the cloth, Raghunath has been colouring his house walls for the last few weeks. This, alongside following his daily routine of making organic colours, is his way of assuring himself and his family that things are going to get better once the pandemic ends.

|

Within the confines of the house, colours explode in a way that looks like you’re part of a festival. But only Raghunath knows the burden of having unsold paintings worth lakhs just lying around.

“Coronavirus has robbed close to 150 families of their livelihoods in our village. We would receive a footfall of 400 people every day before the pandemic, but in the last year, I have not sold even one painting. By colouring the house, our community is keeping spirits high and hoping the world takes notice and buys our paintings,” Raghunath tells The Better India.

Raghurajpur was declared a ‘heritage village’ in 2000 by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). This recognition promoted tourism in the village and assured the artisans that their art is protected. Veteran artists like Raghunath even passed down the art form to their children, knowing it will generate livelihood.

|

Parul Kumar, who has been working with the village artisans for the past few years, says this is the first time they are struggling to make ends meet.

“Through my NGO Prabhaav, we have created market linkages and helped artisans sell the artwork even during cyclones. But the pandemic has restricted movement so we cannot even organise exhibitions,” says Parul.

|

She adds, “Raghurajpur village is full of talent, dedication and hard work, and produces several different types of breathtaking artwork including Pattachitra, cow dung toys, grass baskets, pottery, palm leaf painting and shell work.”

Here are some examples of the beautiful artwork done by the villagers:

CRAFTS IN INDIA

India is one of the only countries with a continuing vibrant tradition of handicraft culture. After agriculture, the crafts sector is the largest employer with over 20 million practitioners. The art and handicraft items produced by the artisans of the Odishan village are required for religious ceremonies, festivals and even decoration of households, lending those artistic opportunities and their livelihood, even on the international scale. The history of Odisha bears testimony to the fact through the evidence of maritime trade. These include a variety of products like appliqué work, textiles, terracotta, and filigree and, of course, Pattachitra. Pattachitra, an ancient art form dating back to 5th century B.C., is a Sanksrit word in which ‘Patta’ means canvas and ‘Chitra’ means picture. The canvas can be of cloth like silk and even palm leaves. The colours used are mainly organic except black which is obtained from the soot of kerosene lamps. Pattachitra is characterised by vibrant colours and craftsmanship and they mainly depict Hindu mythologies, deities and like.

ABOUT THE VILLAGE

The village is situated about 50 kilometres from the state capital on the southern banks of Bhargavi River. Every family in the village is engaged in visual or performing art making it an artisan village. Tropical trees like mango, jackfruit and coconut are common around here and the nearby crops are mainly betel leaves. Various small temples dedicated to Lord Lamxinarayan, Raghunath, etc. and Bhuasuni, the local deity, are found in this village. The artists are engaged in various activities like the talapatta paintings, patta paintings, poetry on dried palm leaves, engravings on palm leaf, carving stone and wooden idols, sculptures, papier mache and making of toys.

The village has 103 houses with about 311 residents, in which many of the master painters are away for the majority of the year. The village comprises two streets oriented along East to West and three rows of buildings. The outer buildings are residential units and the inner buildings are the community buildings like temples and dance practice huts. The three Patas painted by the Chitrakaras in this village are placed on the deity throne of the main Jagannath Temple in Puri, during the fortnight following the full-moon day in the months of MayJune. Raghurajpur village is known for its traditional performing dance, known as Gotipua. This village is the birth place of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, the great Odissi dancer, who popularised it on an international scale.

CASTE

The finish floor level of the dwelling units is at a height of 750mm (5 steps) from the Ground level. This is due to functional reasons so as to inhibit entry of snakes and rainwater but it also served a social function. Higher plinth height meant a higher social standing. Since the state Government intervention, most of the dwelling units have become pucca structure and since they are in row form, the plinth height is same. Though the evils of the caste system are known throughout, the culture of crafts survived here because of the caste system and the local demands for these items. The social immobility of these artisans (called Chitrakars) ensured the continuity of the tradition through generations which highlights a deep inter-relationship between the Chitrakars and the societal structure. The surname of these inhabitants is their professional identity restricting them in their profession and issues like landlessness, small farmers as part time artisans depending on the season, social restrictions exist.

RAGHURAJPUR AS A LIVING MUSEUM

Merriam-Webster defines museum as an institution devoted to the procurement, care, study and display of objects of lasting interest or value. A type of museum where the exhibits are displayed in an unconfined atmosphere, outside an enclosed area can be referred to as open air museum and they include living museums where the goal is to demonstrate the lifestyle and the culture to an outside audience. Similar our study area can be referred to as a repository of living culture unconfined within four walls where everything catches the attention of the tourist in a living form. The activities can be the painting of a pattachitra, making of toys made out of terracotta, cow dung, paddy, betel nuts, lacquer, etc., the way of the inhabitants and so on. Through this, one can discover the social fabric of the village settlements, rural households, the goods being created, their daily lives and so on weaving the story of a rural heritage crafts village.

The houses, on row form, are painted with murals as an artistic skill expression and also act as a display of talent to outsiders passing on the streets. The chitrakars can be seen working on the verandas. In the evenings, one can see Gotipua dance being practiced by many of the residents. The evening rituals at the temples are participated by all the households. All these highlight the continuing tradition of the village and hence make it a living museum.

SUSTAINABILITY

The profession, tradition and the lifestyle of the residents is deeply linked to nature. From the very layout of the village to the individual level, one can observe the natural influences. Earlier the drinking water needs were fulfilled by the Bhargavi River though the residents have switched to ground water. The river still provides the water for religious purposes. The village streets are oriented on the East- West direction which facilitates unshaded streets, which translates to reflected or diffused natural light to the dwelling units. The artisans prefer to work on the verandas or at the entry door of their houses in the presence of natural light. Since the houses are in row format, there is a continuous veranda along the houses which serves as the social interaction space for the residents, both for the male as well as the females, though at different times of the day. This fosters a spirit deeper than neighbourly, more like a family spirit. Originally the performance art used to take place in the village centre, which was an open air kutcha platform, which used to be the focus of the village social interaction in the evenings.

RAW MATERIALS

The process of painting patachitra begins with the preparation of canvas (pata). Traditionally, cotton canvas was used, now both cotton and silk canvas are used for paintings, sourced from nearby villages. White is obtained with conch shell is powered and boiled with kaitha gum, till a paste is formed. Black is formed from lamp black or lamp soot. A burning lamp is placed inside an empty tin, till a considerable amount of soots collects on the underside of the tin. The oil used in the lamp is from polang tree seeds which are locally available. Green is made by boiling green leaves like neem (Asian Tree) leaves with water and kaitha gum. Brown is obtained from Geru stone, whose powder is mixed with gum and water. Red comes from a stone Hingulal, which, is a locally available stone. Blue obtained from a blue stone called Khandneela found in Orissa. Yellow is derived from yellow stone called Hartal, which is found in Jaipur. The finer brushes used by the chitrakars (painters) are made of mouse hair which have wooden handles. These are used for the finer work they do like ornamentation, face etc.Other plane brushes, which are not as fine as the mouse hair brushes, available normally in the market are also used by the chitrakars. All the brushes these chitrakars use lasts for 7‐8 months, when they work daily.

CONCLUSION

The Government of Odisha has stated that in Raghurajpur, every house is a studio and every resident is an artist. Though their profession and tradition is a result of generations of social restrictions, there product is an important part of the state’s household culture. This has also provided them many opportunities to improve their socio-economic status through the intervention of the Odisha government. Their culture of decorating their dwelling units through murals has made the village a living museum, and also their practice of working in an unconfined environment. Their religious ceremonies and celebrations of various social functions further emphasize their heritage. Concepts like sustainability existed through its history of traditions. Though the Government actions has led to the overall improvement in living conditions but certain issues have also been observed such as expansion of the existing one or two room house disregarding lighting and ventilation, lack of use of the guest house, etc. In spite of them, its positive aspects to highlight the importance of the village as a symbol of a living cultural heritage outweigh the issues.

References

- Bindloss, J. and Singh, S., “Southeastern Orissa- Raghurajpur”, Lonely Planet, ISBN 1-74104-308-5., 2007.

- Bundgaard, H., “A Crafts Village and its Making., Indian art worlds in contention: local, regional and national discourses on Odishan patta paintings”, Routledge publications., 1999.

- Dash, P. K., “Tourism and community development-A Study on Handicraft Artisans of Odisha”, International Journal for Innovation Education and Research, Vol.3-3., 2015, pp. 124- 138.

- Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage., 2007., “A case study in sustainable Rural Heritage Tourism”, INTACH publications., 2007.

- Mohanty, P., “Rural Tourism In Odisha- A Panacea For Alternative Tourism: A Case Study Of Odisha With Special Reference To Pipli Village In Puri”, American International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Vol. 14-557., pp 84-102., 2014.

- Mishra, M., “Artisan Villages of Odisha: A concept of Open Air Museum”, Odisha Review, Vol. 71-9., pp 80-83., 2015.

- Samantray, P. K., “Pattachitra- Its Past and Present”, Orissa Review, December issue., 2005.

- Tripathy, M., “Folk Art at the Crossroads of Tradition and Modernity: A study of Patta Painting in Orissa”, Journal of the Anthrpological Society of Oxford, Vol. 29/3, Oxford publications., 1998.

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Jagannath Temple administration issues clarification on proposed sale of temple lands

- The forgotten temple village of Bharat: Maluti

- Dear NSUI, Bhagat Singh And Subhas Chandra Bose Admired Savarkar And His Ideas

- A new symbol of Hindutva pride, Shri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Corridor

- Biggest Wonder of the World : Kitchen of Lord Shri Jagannath

- Why India’s temples must be freed from government control

- Shri Murudeshwar Temple: Home To The World’s Second Tallest Shiva Statue

- Culture And Heritage - Meenakshi Temple Madurai

- Srikalahasti Temple, Dakshina Kailash

- Madras High Court: Do not take decision on melting Temple gold till Trustees are appointed

- Why Hindus not claiming their temples back from the Government control: Is pro-Hindu govt will always be in power

- A Different 9/11: How Vivekananda Won Americans’ Hearts and Minds

- अथ रामचरितमानस प्रकाशन कथा: गीता प्रेस, गोरखपुर ने 1938 से रामचरितमानस का प्रकाशन शुरू किया

- Indonesia: Sukmawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of Indonesia's first president becomes a Hindu leaving Islam

- Manyavar commercial featuring Alia Bhatt vilifies Hindu wedding ritual Kanyadaan: Why not object Western practice of ‘giving away the bride’ and Nikah (marriage contract)