More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

"Yogi seemed to be doing everything wrong, yet everything came out right": Story of an Unknown Hindu Yogi from the annals of freedom fights, who with a muscular build, sitting on a leopard skin killed a British Captain in front of the British Army in 1857

In 1857, Indian soldiers rose up against their British commanders. They were joined by native rulers and thousands of ordinary people in a struggle that threatened to destroy British colonial power on the Indian subcontinent. The reasons behind the rebellion stretch back to the origins of British involvement in Indian affairs.

The Sepoy Mutiny was a violent and very bloody uprising against British rule in India in 1857. It is also known by other names: the Indian Mutiny, the Indian Rebellion of 1857, or the Indian Revolt of 1857.

In Britain and in the West, it was almost always portrayed as a series of unreasonable and bloodthirsty uprisings spurred by falsehoods about religious insensitivity.

In India, it has been viewed quite differently. The events of 1857 have been considered the first outbreak of an independence movement against British rule.

The uprising was put down, but the methods employed by the British were so harsh that many in the western world were offended. One common punishment was to tie mutineers to the mouth of a cannon and then fire the cannon, completely obliterating the victim.

|

The War of Independence of 1857! Part of the many divisions of the British army marched towards Kanpur, then called Cawnpore, from Calcutta on the 21st of September. They were to reach Lucknow via Benares, Allahabad, Futtehpore, and Kanpur. Around 2200 Indian sepoys had laid siege to the British Residency in Lucknow including Sikandar Bagh. Sikandar Bagh was a villa and garden spread over an area of 4.5 acres located in Lucknow. It was built as a summer residence during the first half of the 19th century by Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Oudh. This villa had a fortified wall along the boundary on all four sides.

The Ninety-Third Sutherland Highlanders, also a part of the British army, used rail, and bullock carts to reach this destination. They also marched on foot, especially in areas where rail facility was not available. Elephants were used to carry tents and other necessities including ammunition. En route to Kanpur, the Highlanders reached Benares on the 17th of October 1857.

|

The British Army dreaded the freedom fighters of the region from Benares to Allahabad. In the words of William Forbes-Mitchell, a Sergeant with the Ninety-Third Sutherland Highlanders, who wrote about the 1857 War of Independence in his book Reminiscences of the Great Mutiny, “From Benares, we proceeded by detachments of two or three companies to Allahabad; the country between Benares and Allahabad, being overrun by different bands of mutineers, was too dangerous for small detachments of one company.”

According to this book by William Forbes-Mitchell, railway tracks have been built up to Lohunga, about forty-eight miles from Allahabad. This line was to connect Kanpur. No stations were built. A considerable force of the British army assembled in Allahabad.

Missionary workers involved in converting the Hindus to Christianity were active in this region during that time. Mitchell mentions meeting a group of missionary workers at Futtehpore, located seventy- two miles from Allahabad. He wrote, “I met some native Christians whom I had first seen in Allahabad, and who was, or had been, connected with mission work, and could speak English. They had returned from Allahabad to look after a property which they had been obliged to abandon when they fled from Futtehpore on the outbreak of the Mutiny.” This proves that the War of Independence of 1857 affected missionary workers too. Had the war been a success, India would have been a different nation today! Maybe there was a lack of communication amongst the freedom fighters across the length and breadth of the country, which led to their failure.

Freedom fighters from Banda and Dinapore and adjoining areas, “numbering over ten thousand men, with three batteries of regular artillery, mustering eighteen guns” crossed the Yamuna River to check the advances of the British army. Mitchell mentions about this in his book, but there is no mention of whether any skirmish between the two forces occurred.

The British Army reached Kanpur. Indian sepoys and civilians of Kanpur laid siege to the city in June 1857. The sepoy forces captured 120 British women and children, killed them, and threw their dead bodies in wells. This came to be known as the Bibighar Massacre. The incident drew hateful criticism from the British in India and their home country. The angry British recaptured Kanpur and started widespread retaliation, killing, and hanging of captured sepoys and civilians. Brigadier Wilson of the Sixty-Fourth Regiment was in command of Kanpur when more forces of the British directed for Lucknow reached this city.

Mitchell happened to meet a man, a local guide, a Mohammedan from Peshawar, who could speak broken English and who knew many secrets. He took him to the “slaughterhouse in which the unfortunate women and children had been barbarously murdered and the well into which their mangled bodies were afterward flung.”

The Peshawari guide narrated a secret related to Nana Sahib, who led the uprising in Kanpur. Nana Sahib was the adopted son of the exiled Maratha Peshwa Baji Rao II and adopted brother of Rani Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi. According to the guide’s account, Nana Sahib, through a spy, tried to bribe the commissariat bakers who had remained with the English. He asked them to put arsenic into the bread they baked for the British. The bakers were Mohammedans. They refused to add poison to the bread. After the Bibighar Massacre, Nana Sahib had these bakers “taken and put alive into their own ovens, and they're cooked and thrown to the pigs.”

|

The British army marched from Kanpur towards Lucknow. They reached the outskirts of a village on the east side of Secunderabagh (Sikandar Bagh) in November (1857). They made a short halt at the center of the village. They came across a Yogi in meditation, which Mitchell described as a ‘naked wretch’. The British never termed the Indians with respect then. The Yogi looked like a bodybuilder. His head was cleanly shaven except a shikha (a tuft of hair at the back of the head) adorning it. It was a ritual followed by not only Brahmins but also many other Hindus. Out of the seven chakras or energy centers in the human body, the shikha is believed to cover that part of the skull wherein lies the Shasrara Chakra. The tuft of hair is retained to protect it. Mitchell’s book finds no mention of the name of this Yogi. His body was smeared with ashes and his face was painted white and red. He was seated on a leopard’s skin. He was counting a rosary of beads when the British army saw him.

In the words of Mitchell, the Yogi “was of a strong muscular build, with his head closely shaven except for the tuft on his crown, and his face all streaked in a hideous manner with white and red paint, his body smeared with ashes. He was sitting on a leopard’s skin counting a rosary of beads”. The white and red paint that the Yogi applied on his face might be chandan and kumkum. British could perceive it only as paint.

James Wilson, a British soldier aimed his bayonet at the Yogi, addressing him as a ‘painted scoundrel’ and ‘murderer’. Another officer, Captain AO Mayne, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General of that troop, stopped him. Mayne said that Hindu Yogis were harmless. He had just scarcely uttered the words and his sentence not yet completed when the Yogi stopped counting the beads, took out a pistol, and fired at the chest of Captain Mayne in seconds. It all happened at lightning’s pace! Mayne lay dead. The British army could not stop his action then.

|

Here is what Mitchell described the encounter:

About the center of the village, another short halt was made. Here we saw a naked wretch, of a strong muscular build, with his head closely shaven except for the tuft on his crown, and his face all streaked in a hideous manner with white and red paint, his body smeared with ashes.

He was sitting on a leopard's skin counting a rosary of beads. A young staff officer, I think it was Captain AO Mayne, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General, was making his way to the front, when a man of my company, named James Wilson, pointed to this painted wretch saying, "I would like to try my bayonet on the hide of that painted scoundrel, who looks a murderer."

Captain Mayne replied: "Oh don't touch him; these fellows are harmless Hindoo jogees, and won't hurt us. It is the Mahommedans that are to blame for the horrors of this Mutiny."

The words had scarcely been uttered when the painted scoundrel stopped counting the beads, slipped his hand under the leopard skin, and as quick as lightning brought out a short, brass, bell-mouthed blunderbuss and fired the contents of it into Captain Mayne's chest at a distance of only a few feet. His action was as quick as it was unexpected, and Captain Mayne was unable to avoid the shot, or the men to prevent it.

Immediately our men were upon the assassin; there was no means of escape for him, and he was quickly bayoneted. Since then I have never seen a painted Hindoo, but I involuntarily raise my hand to knock him down.

Immediately, the army was set to action. The Yogi was already surrounded by thousands of the British army at the time of the assassination. They quickly bayoneted and shot him dead.

Was he really a Yogi? Or was he only waiting, disguised, to kill a high-ranking British officer without fearing for his life? No records of History mention this! Thanks to the account by Mitchell. Salute the valor of the unknown Yogi.

Jai Hind!

References:

Saffron Swords: Centuries of Indic Resistance to Invaders - Manoshi Sinha Rawal, Yogaditya Singh Rawal

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- "दधीचि": Jatin Das, hailed by Netaji as the "Young Dadhichi," fasted unto death for 63 days in Lahore Jail, enduring brutality while protesting British tyranny, his martyrdom ignited national outrage, inspiring millions in the fight for India's freedom

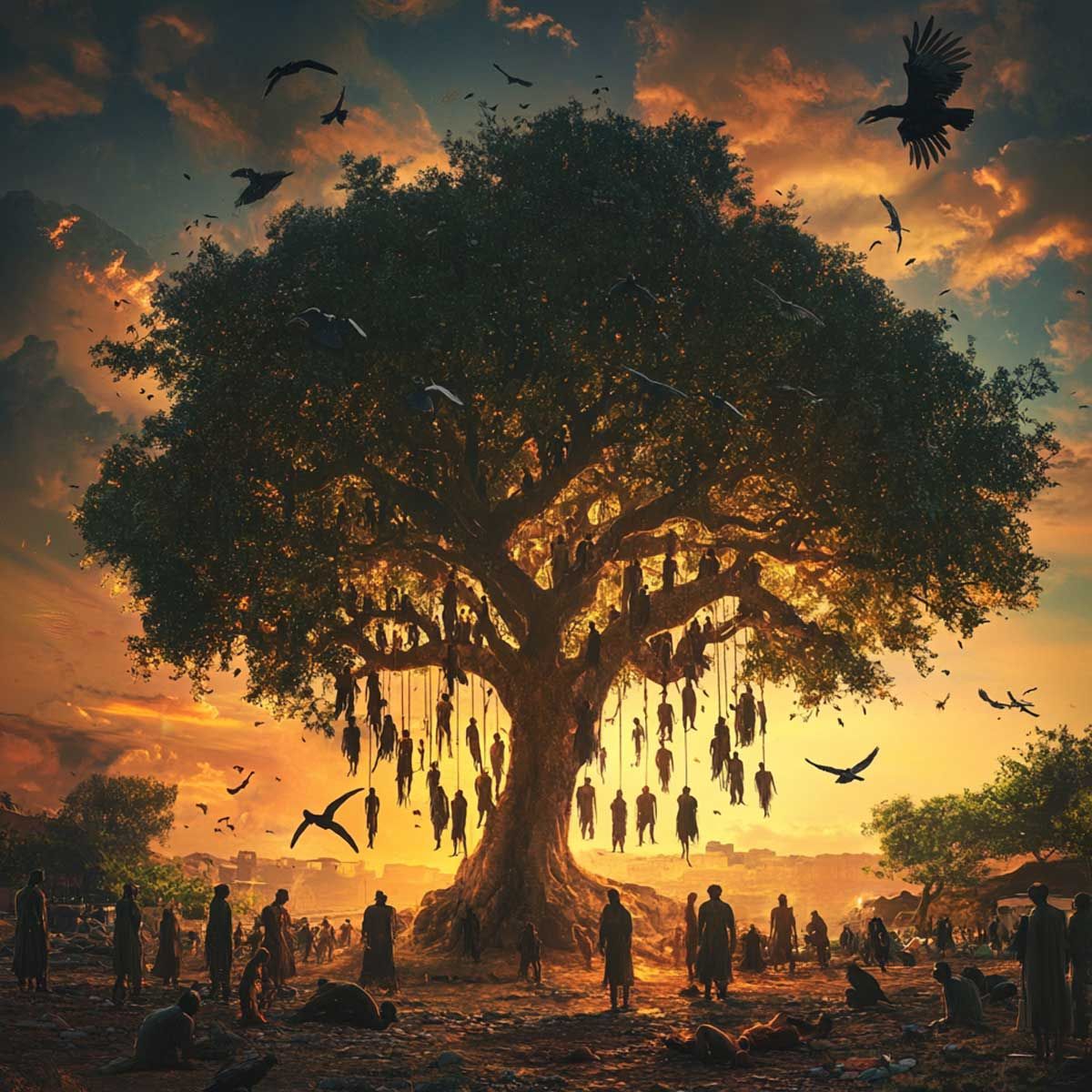

- "बावनी इमली": In 1858, at Bawani Imli in Fatehpur, 52 revolutionaries led by Jodha Singh Ataiya were brutally hanged from a tamarind tree by the British, a forgotten chapter of India's freedom struggle buried under decades of silence and neglect

- Rana Sanga, the symbol of bravery who defeated Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi and fought Muslim Terrorists for Hindu Existence

- "You can't serve the public good without the truth as a bottom line": Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi - activist journalist who used journalism to aspire political engagement & develop critical thinking among the masses, who lived- and died- for communal harmony

- "Courage makes a man more than himself; for he is then himself plus his valor": Surya Sen - hero behind Chittagong armory raid & attack on Europeans only club that shook British like never before, brutally tortured and executed by British on Jan 12, 1934

- Debunking the myth of "De Di humein Aazadi Bina Khadag Bina Dhal": Bharat’s founding story bestows upon it an extravagant national philosophy and long-lasting costs

- "The tyrant dies and his rule is over, the martyr dies and his rule begins": Paona Brajabashi - Fearless Manipur General who valiantly led his 300 soldiers in one of the fiercest battles in history in the Battle of Khongjom against the British in 1891

- A Great man Beyond Criticism - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- "Victory are reserved for those warriors who are willing to pay it's price": One of the greatest and undefeated General Zorawar Singh conquered Laddakh, Tibbat,Gilgit, Skardu, Baltistan and defeated army of Imperial Chinese Tibetans in Dogra-Tibetan War

- "Sing your death song and die like a hero going home": Courageous saga of Lachit Barphukan: Heroic defender of Assam who defied the Mughals, igniting a flame of Nationalism and Resilience for generations to embrace and preserve India's glorious heritage

- Add Vedas and review freedom fighter's portrayal in School textbooks: Parliamentary Committee on Education

- "Behold it is born. It is already sanctioned by the blood of martyred Indian youths": Madam Bhikhaiji Cama, the Brave lady to first hoist India’s flag on foreign Soil - Formative Years

- Jhalkaribai: The Indian Rebellion Of 1857 Who Took on British Forces Disguised as Laxmibai

- The Trap in Lahore - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- "The tyrant dies and his rule is over, the martyr dies and his rule begins": Baji Rout, a boat boy - youngest martyr of India's freedom struggle who was manhandled, threatened & skull fractured but refused to ferry British police across the Brahmani River