MORE COVERAGE

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

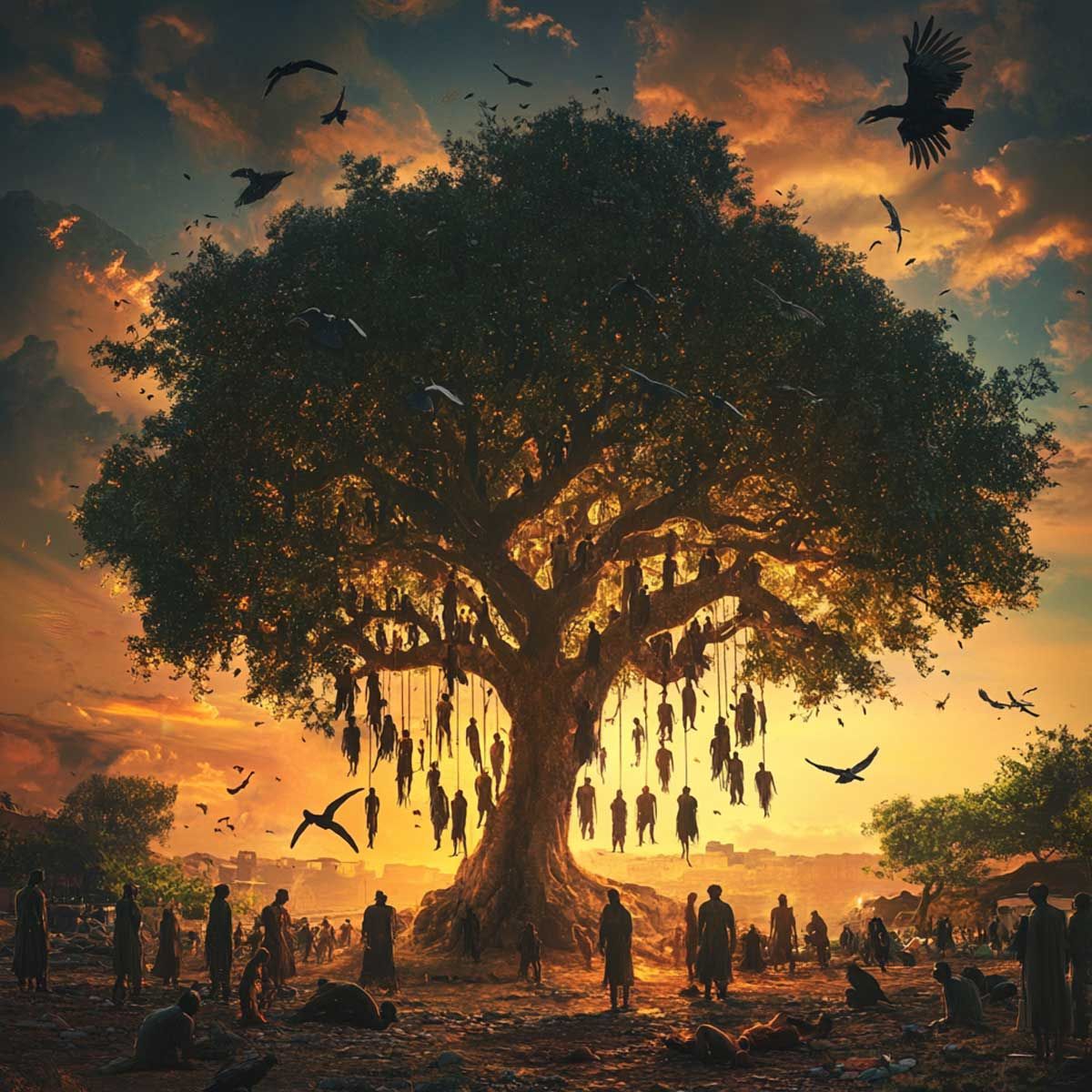

"Never mind a world that can't see past brutality": Leopold of Belgium killed 15 million Congolese people in 23 years of his rule in Congo by promising a humanitarian & philanthropic mission that would improve lives of Africans, thats how narrative is set

Belgian King Leopold II set out for the Congo and declared it his territory while physically intimidating the indigenous people of the Congo (Kongo). He proclaimed his property to be the people and the land, and he quickly turned the land into a money-making enterprise for himself and his throne.

The Kongo was rich in many minerals, but at the time it was richer in ivory and rubber. He set up a system that was extremely harsh on the people — a system that, if they did not reach regular quotas, murdered and mutilated the indigenous people.

In their territory, the people of the Kongo were then enslaved. The Europeans found some way to loot from the Africans, and kill them in large numbers while at it, because slavery had been aborted and abolished.

|

The Exploration and Mapping Out of The Congo (Kongo)

King Leopold II had to study and map out the Congo after the Belin Conference in order to decide its capital, people, and best routes for his intended invasion.

He employed a British adventurer called Henry Morton Stanley and sent him to the Congo. Stanley’s job was to create the Free State of the Congo. He picked Stanley since he was the European who mapped out the Congo River, he had some kind of experience with the people and the region.

Although historians have suggested that Stanley had no original intention of harming the people of the Congo, many still do not agree that he should be excluded from his crimes against the people. Without the invitation of the indigenous people, his first offence was to reach the Congo and then go ahead to map out their land without their permission.

The presence of him and his men offended the Congo natives, and misunderstandings as well as later confusion fuelled this.

Stanley and his men were faced with and confronted by seven different indigenous peoples of the Kongo. In his journal, people had witnessed Stanley's writing, and for them, it was some witchcraft or a conspiracy to destroy them. They asked him to burn his book, or it would destroy him and his men. Clearly, the natives did not want what was in his journal to get out of their territory. The gods were wise, and that was for good reason.

Stanley continued his discovery and expedition and, whenever they came near or he saw them, began to fire at the people of the Kongo. By the time he had gotten to the end of his exploration, he had succeeded in burning down over 32 towns of the natives and killing many of them.

His men were out of control, and all kinds of crimes were perpetrated against the people of Kongo. They went about abducting and raping the women for some minor misunderstandings and flogging the men to death.

This was how, on the foundations of terror, murder, rape, and arson, the Congo Free State was founded.

|

The Enslavement of The Entire Kongo Population

When Stanley sent his report to King Leopold, temples loaded with ivory (elephant tusks) and the abundance of rubber in the Congo were confirmed. The wealth was lavish, and Leopold was determined to create profit from it.

By violence, King Leopold II took possession of two-thirds of the land of the Kongo and ordered the real owners of the land to serve as slaves for him. Some sources stated that people were paid pennies for their labor, but it was soon stopped and then forced to work without pay for 20 days a month.

King Leopold II’s government and officials declared that rubber harvesting was then a necessary tax that would be paid to the crown by those who lived on the land. This literally meant that Leopold took the lands and wealth of a people and obliged them to work on their own land as slaves.

The officials of King Leopold II made the quotas very wide and difficult to reach, because of the high expectations of riches and benefits from rubber and ivory. This meant that people would be able to fulfill their rubber quota for 20 days, and then they would be left with the remaining 10 days a month to farm and work and provide food for themselves and their families.

The Maiming and Killing of Congolese Who Didn’t Meet Their Quota

By the 1890s, the rubber quota of the then devastated and oppressed Congolese was raised by Leopold II through his officials. The rubber industry in Europe was booming and he had to meet the demands of the market. That meant the indigenous people had more working hours. As the punishment for not fulfilling the quota was the cut-off of your limb or death, the situation turned from bad to worse.

Leopold II had an army that consisted of about 19,000 soldiers. They were European mercenaries employed and even acted as a police force to defend their government and business interests. They were called Publique Force. The military aggressively recruited Africans into its lower ranks as well. These Africans were press-ganged into service and they were executed if they resisted.

It was the Force Publique that introduced the rubber tax quota to be collected by the people. Some of the officers were African, but a vast majority were white and were made to follow these laws.

The European officials were so ruthless and based on their rubber hatred and targeting that they created a rule for soldiers to cut off and deliver the hands of any of the Congolese citizens killed for failing to fulfill their quota.

They would have them present a basket full of their people’s hands or face execution to punish the Congolese men whom they had forced into service. This was a way to turn people against themselves, a tactic that Europeans used to divide people all over the world, particularly in Africa.

The source began to decline thus becoming slightly scarce after several years of collecting and tapping the rubber in the Congo. It was then more difficult to obtain the rubber, as many individuals had to climb tall trees to reach the vines. People may often drop from the trees and fall to their deaths.

The risk of losing your limb or being killed often prompted the Congolese to cut the vine off, so that more rubber sap could be tapped. It succeeded, but it meant that those vines were useless then, and in the future, they could not be tapped again. So, it was also an offense to cut off the vine, punishable by death or serious beatings.

One day, a commissioner captured a Congolese man who had cut a vine. In his journal, he wrote a note of advice about it and said, “We must fight them until their absolute submission is obtained…” or their complete extermination.

Some commissioners would not execute people who did not fulfill their quota, or cut off their limbs. They beat them so badly that some died, though, beyond recognition, the majority were wounded.

To keep count of their quota, the Congolese workers were given discs to wear around their necks. Any Congolese who did not meet his quota would be caned 25, and most of the time 100 whip lashes made of hippopotamus hide. These whips had the power to peel off the skin once it came into contact with the skin.

|

The Death of Millions Was Caused By Disease

In addition to the shooting and maiming of Congo’s indigenous people, the disease was another factor that caused millions to die. The well-being of the workers was not taken into account by the Belgians, who fed them unhealthy meat and vegetables and starved them most of the time.

With all the human components and the destruction of the natural world, the environment has been turned unhealthy. The rotten food caused the men to become ill, and an epidemic broke out.

To extract the rubber, the men had to go into the deep jungle and they were bitten by the Tsetse fly that spread untold sickness and deaths across the Congo and even into other African nations.

About 350,000 people in Kongo alone were wiped out by sleeping sickness that sometimes led to death. Please note that this umber is a conservative figure.

However, this did not make the Belgians stop. For the commercial benefit of their resources, they continued the slavery and enslavement of the people of the Congo.

The Burning of Congolese Villages

The study and accounts of the many crimes against the Black man are one that will literally tear up any other Black person. Researchers were forced several times to pause in frustration and disbelief during the course of gathering facts like this.

The burning of their villages was one of the painful accounts of the genocide of the Congolese. The commissioners and their officers also gave a certain quota to a whole village to fulfill. The soldiers would surround the village, kill the inhabitants, and then burn the village to the ground if a village failed to fulfill its quota.

The soldiers burnt down villages in a specific village, killed 50 of the men, and took 28 of the women as prisoners, with chains around their necks. This specific village had fulfilled its target, but was still killed and burned because the officers said the rubber tapped by the villagers was not of good quality. This brutality was carried on by inhuman people.

|

The Torture of Women and Children for Quota Fulfillment

Torture and amputation were the required instruments for the Belgian officials and their European mercenary troops to pressure the citizens to be terrified and to work for free.

They were feeding off the fears of the Congolese people, through psychological terror. It was reported that the European soldiers would kidnap the women from the villages that didn’t meet their rubber quota, so as to force the men to meet their quota. Most of the women were kept as prisoners and slaves by the Europeans.

To make things worse, after they reached their quota, the men would have to buy back their wives with their living stocks.

A soldier was asked on a specific occasion to raid a town that had not met their quota. He was given strict orders by his commander to decimate the town and make an example of them.

He gave details saying that: “He ordered us to cut off the heads of the men and hang them on the village palisades, also their se*xual members,” the soldier said, “and to hang the women and children on the palisade in the form of a cross.”

During their time in Kongo, this was how evil the Europeans were.

The Intervention by The International Community

For more than a decade, the crimes of King Leopold II and his army persisted until it reached a point where the missionaries had to write in protest to the different governments and organizations of the world.

The evidence provided by the American missionary, G.W. Williams and authors like Mark Twain and Joseph Conrad were influential in the investigation of the crimes of King Leopold II.

A British journalist named Edmund Dene Morel, a British diplomat named Casement, and a missionary named William Shephard were those who gave reports on the genocide.

In the international media, the accounts and reports of these men and many others were released, paying much attention to the evil that was going on in the Congo. Many people around the world had called out against the atrocities and called for the respect of human rights.

When an investigation was completed, the several pieces of evidence that were presented in the findings were then verified in 1905. A damning report on the genocide that was going on in the Congo was released by the commission responsible for the investigation.

The Commission’s findings, along with the missionaries’ reports, raised a great number of protests from other governments and the Belgian people against King Leopold II.

Diplomatic talks and pressure from many quarters would later lead Leopold II to renounce his rule over the Free State of the Congo and then hand it over to the Belgian Government, and then the Congo to be named the Belgian Congo.

He and his brutal soldiers walked away untouched after the atrocities, leaving the people of the Congo to suffer the consequences of the genocide for the next 100 years and more. To this day, the Congo is still the property of the Europeans and has been held in constant conflict by European powers trying to seize their wealth while keeping the citizens divided.

It would educate you to know that Killer Leopold II’s whole carving of the Congo did not first come in the form of genocide. Oh, no. he traveled to the Congo as a charitable and humanitarian group.

He came with gifts and vowed to improve the living conditions of the people of the Congo for the better. And it was said that his charitable organization had received major donations from around the world.

With such smooth and convincing words, he impressed the people of the world and made them think that donating to his course was the holiest and most noble thing to do. In a speech, he said: “To open to civilization the only part of our globe which it has not yet penetrated, to pierce the darkness which hangs over entire peoples, is, I dare say, a crusade worthy of this century of progress.”

However, they didn’t realize that he was secretly searching for funds for massive military forces and infrastructure to facilitate and enslave the citizens of Congo.

Leopold II was heard behind closed doors telling one of his ambassadors that “I do not want to miss a good chance of getting us a slice of this magnificent African cake.”

This, in Africa, is the legacy of King Leopold II. And while he was tearing apart Congo, in other parts of the continent, the British, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, and others were busy slaughtering Africans and stealing their resources.

|

Once the Blood on Our Hands Dries: Royal Apologies for the Belgian Colonization of Congo

s the saying goes, ask for forgiveness, not for permission. Throughout history, colonial nations have become familiar enough with this ideal to make it their own: colonize now, and apologize later.

Nearly 150 years after its colonization of the Congo had begun, Belgium has now entered its era of apology. In June 2020, on the anniversary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s independence, King Phillipe of Belgium wrote a letter to Congolese president Félix Tshisekedi, expressing his “deepest regrets” for the acts of colonial violence inflicted upon the Congolese people during Belgian rule. This letter is widely regarded as a milestone in the nation’s present-day conciliation with its colonial legacy; it marks the first time that a Belgian king openly expressed regret for the brutalities of the colonial dominion. With this precedent established, he would not be the last royal to do so.

In February 2022, Princess Esméralda of Belgium furthered the sentiment of her half-nephew’s letter in an interview with Agence France-Presse (AFP), calling for the nation of Belgium to apologize. Controversially, she compares the two nations’ post-colonial relationship to a romantic one, stating that “as in a couple, apologies are important to restart a balanced relationship." Though Belgium’s motto translates to “unity makes strength,” the Belgian Royal Family’s public statements of remorse and apology have created a divided response; what some—including Belgian ministers—considered unnecessary, others considered inadequate. For instance, in a 2020 interview with Democracy Now!, Belgo-Congolese journalist and activist Gia Abrassart describes herself as a “fruit of the shared history” between Belgium and Congo and relays the insufficiency of apologies alone in improving the lives of Congolese people. She states, “we would like to work not on the… memorial reparation, because it [colonization] has still an impact today on us, on the new generation, on the Afro-descendant generation.” The controversy regarding Belgium is seated in a greater discussion on retributions for inequities of colonialism, including who, if anyone living, is to blame. Blood was shed conspicuously, but the extent that royal apologies can atone for it remains contested.

You’re not your ancestors…

After calling for Belgium to apologize, Princess Esméralda received “a lot of mail” criticizing her stance. She then clarified her position, stating: “We are not responsible for our ancestors,” but “we have a responsibility to talk about it.” The staunch opposition to Esméralda’s statement is representative of how discussions around colonization are often derailed. The focus is no longer on providing justice, but on avoiding blame by distinguishing oneself from the actions of those who came before.

Perhaps Princess Esméralda and King Phillipe have the clearest incentive to make this distinction. They are both direct descendants of King Leopold II, who, in the name of “civilization” enacted what became known as one of the world’s first major genocides. When worldwide demand for rubber increased, Leopold found an opportunity to make a profit and embark on a vanity project. After receiving permission from European leaders at the 1885 Berlin Conference, Leopold turned the land of Congo into his colony, naming it the Congo Free State (CFS). This “free” state became the framework of a savage system of exploitation, resulting in the deaths of over 10 million Congolese people while generating Leopold 220 million francs (or US$1.9 billion in today's dollars) in profits, though many historians view these as conservative estimates. Journalist and historian Tim Stanle vividly depict the hellish colonial reality that Leopold created, writing:

In the aftermath of these tragedies, the Belgian Royal Family tends to distance themselves from the actions of their ancestors. Nothing could ever wash the blood of ten million from their hands, so they prefer to believe that generational time has dried it, let it flake away, and left their hands clean. But blood leaves behind stains, and even under the finest gold regalia and precious embellishments, it remains to tell these horrors of the past.

…but their colonial legacies did not die with them

Tragically, these past horrors shape present realities. In February 2019, the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent released a media statement regarding its conclusions after its official visit to Belgium. Their evaluation of the current state of Belgian society concluded that racial discrimination, xenophobia, and Afrophobia exist in the present day because Belgium has not confronted its colonial legacy. As a result, the systemic exclusion of Afro-Belgians from “employment, education, and opportunity” persists. In light of their findings, the Working Group does not call on Belgians to assign or evade individual blame for the nation’s colonial past but to focus on the damaging impacts it has on people of African descent in the present. They assert that colonialism and decolonization cannot be merely understood as taking land and giving it back; colonialism is a violent process that infiltrates and alters every aspect of society, resulting in extreme poverty and brutal conflicts. Any decolonization effort would not be complete without mitigating these perverse, contemporary effects. For instance, Congolese people who are from former CFS concessions, land that Leopold granted to private companies to extract resources and labor from, have significantly less wealth, fewer years of education, lower literacy rates, and lower height-to-age percentiles than those who were not from former concessions, despite the geographic and cultural similarities between these areas. With this present-day reality in mind, future discussions should not center around post-colonial guilt, but on post-colonial retribution.

Reparations begin by listening to the victims of colonialism themselves. In October of 2021, a crime against humanity lawsuit was brought before a court in Brussels by five biracial women who were forcibly separated from their Black mothers under Belgian colonial rule. The women did not request apologies, but reparations of 50,000 euros (about US$58,000 each. Plaintiff Monique Bitu Bingi stated in an interview with the AFP: "We were destroyed. Apologies are easy, but when you do something you have to take responsibility for it." André Lite, who served as the Congolese Minister of Human Rights, further detailed how unimpactful mere apologies are, relaying to Anadolu Agency that “The regrets of certain Belgian officials will never be enough in the face of their obligation to grant reparations to the victims of colonization and their relatives.” It is clear that to those who suffered from the Belgian colonization of Congo, regret alone cannot serve as restitution. Though admitting colonial wrongs was long overdue, it is not the end to reconciling with the nation’s past, but the beginning.

In the end, the future of Belgian-Congolese relations relies on Belgium’s ability to focus on the blood that was shed, not on arguments over whose hands it has made unclean. Previous financial allocations to support gender equality, just governance, sustainable development, and technical and vocational education have had more of an impact than words alone ever could, including funding civil society organizations (CSOs) that are designed to meet the specific needs of various Congolese communities. As Abrassart stated, “…reconciliation—and, I would add, reparation—it means material and memorial—will really create a collective therapy for all the Belgians, including the post-colonial bodies like Congolese, Burundians and Rwandans.” Amidst rampant food insecurity, extreme poverty, and a refugee crisis induced by post-colonial conflict, Congo can only benefit from Belgium’s actions, not their apologies. One does not have to become their ancestors to realize that past regimes have present implications and that by moving beyond remorse and toward results, colonial wrongs can one day be righted.

References:

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Maligning of India by British Raj since the 1800s

- The Balliol college at the University of Oxford has dedicated a new building after Dr. Lakshman Sarup, the first candidate at Oxford to pass his thesis for a Doctorate of Philosophy (DPhil) degree on Sanskrit treatise on etymology

- Cross Agent and the hidden truth of massacre of Jallianwala Bagh - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- "PM Modi mentions the 1966 bombing of Mizoram": When Indira Gandhi had ordered the IAF to carry out an aerial attack in Aizawl and its aftereffects that still reverberate in India's history, capturing Mizoram's tumultuous journey through adversity

- Winning wars but losing the peace: Sri Krishna and Mahatma

- The Islamic Doctrine of Permanent War: Jihãd and Religious Riot

- Top of broken pillar in foreground with the famous Sarnath lion capital standing on the ground beyond - 1905

- "Tied to the cannon and blown to pieces couldn't deter his loyalty to Ettayapuram King and his devotion to the motherland stood sturdy and unshaken": Veeran Azhagumuthu Kone, Tamil Warrior who rebelled against Britishers 100 years before 1857 war

- "An Imperial Story of Conspiracy, Loot and Treachery": Maharaja Ranjit Sing's son Duleep Singh, last king of Sikh empire converted to Christianity, lost 'Kohinoor' to Queen and buried in UK with Christian rites despite the fact that he returned to Sikhism

- Tirot Singh: An Unsung Hero of the Khasi Tribe who destroyed British with his skill at Guerrilla Warfare

- The untold exodus of 1.5 lakh Punjabi Hindus to Delhi’s Piragarhi camp; forced upon by Sikh radical Khalistani terrorists led by Bhindranwale

- "Nak-Kati-Rani": Defying Shah Jahan, Rani Karnavati of Garhwal inflicted unprecedented humiliation on the Mughal army, cutting off their noses; her invincible spirit remain unsung in mainstream history, overshadowing the grand tales of emperors

- Indira Gandhi’s bahu published intimate photos of Jagjivan Ram’s son in her magazine: This 'Saas-Bahu ki Saajish' mothered India’s first major political sex scandal which cost Jagjivan his political career

- "One may reject the claims of sainthood made on Gandhi's behalf… and therefore feel that his basic aims were anti-human and reactionary", George Orwell’s Devastating Critique in his article 'Reflections on Gandhi'

- After removing 500 tons of garbage, 18th-century old stepwell to soon serve with clean, fresh groundwater gushing from 53 feet deep water stream: Nalla Pochamma Temple, Telangana