More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

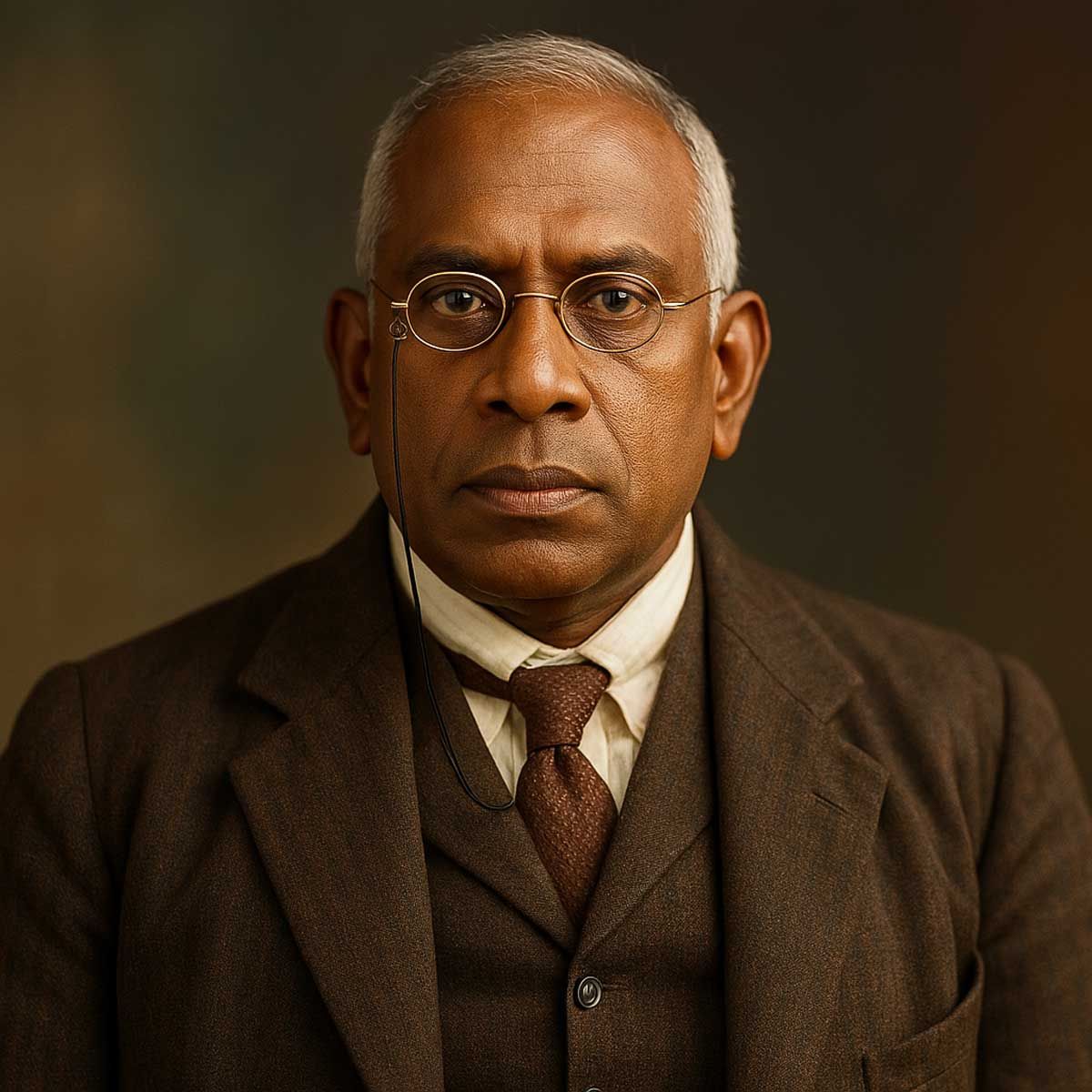

"The Forgotten Father of Armed Revolution in India": Vasudev Balwant Phadke led the first militia in 1879, rallied 300 armed Ramoshis, looted British treasuries, escaped Aden jail, and died on hunger strike—igniting freedom long before Bhagat Singh

In the mid-1870s in Pune, and a man with a light complexion and a strong build dashes through the streets. In his 30s, he carries a thali—a metal plate—and a ladle, banging them together to grab attention. As the sound echoes, he shouts to everyone within earshot, "All should come to Shaniwar-wada grounds this evening. Our country must be free. The Englishmen must be driven out. The ways and means of doing it, I shall explain in my speech."

|

This was no ordinary man stirring up noise. This was Vasudev Balwant Phadke, a name that would echo through history as one of India’s first revolutionaries, often called the 'Father of the Indian Armed Rebellion.' Born on November 4, 1845, in Shirdhon village, Raigad district, Maharashtra, he came from a simple Marathi Chitpavan Brahmin family. His parents, Balwantrao and Saraswatibai, raised him in modest circumstances. His grandfather, Anantrao, had once been the Commander of Karnala Fort until the British seized it in 1818.

Phadke’s life took a dramatic turn from being "a trusted and pampered clerk" in the British Military Finance Department to becoming a fierce rebel leader. What’s remarkable is that he wasn’t royalty—he was an everyday man who dared to challenge colonial rule. Historians note he was the first non-royal to lead such a revolt against the English, setting the stage for future freedom fighters. According to records from the Maharashtra government’s cultural archives, his actions inspired a wave of resistance that rippled across India (source: Maharashtra State Gazetteers).

Just over 20 years after the 1857 revolt—sometimes called the ‘first war of Independence’ or the ‘sepoy mutiny’—was crushed, and the British Crown took over from the East India Company, Phadke sparked a new fight. Rebels under his influence began attacking British interests. They cut railway lines, snapped telegraph wires, stopped mail deliveries, and sometimes blocked news from spreading across the country. Their goal was clear: swaraj, or self-rule. Their plan was to create chaos, disrupt the government, and inspire thousands of Indians to rise against foreign rule. In Pune, the British grew nervous. Major Henry William Daniell, the District Superintendent of Police, got word that Phadke was the mastermind. By 1879, the British issued a lookout notice for him, offering a hefty reward of Rs 4,000 for his capture—a huge sum back then.

It’s hard to believe that just a few years earlier, Phadke had been "a trusted and pampered clerk" in the Military Finance Department. Two spots in Pune tell the story of his change. First, there’s the rooms above Narsingh Temple in Sadashiv Peth, where he lived with his family and read the Guru Charitra Pothi under a peepal tree. Then, there’s the Vasudev Balwant Phadke Smarak near Sangam Bridge in Shivajinagar, where he was jailed and faced trial. Across Pune’s libraries, you’ll find copies of Anand Math by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, a book inspired by Phadke’s rebellion. A booklet from the Lok Sabha Secretariat in 2004, when his portrait was unveiled in Parliament, sums up his legacy: "Vasudev Balwant Phadke was undoubtedly among the first brigade of Indian revolutionaries and soldiers of freedom. His life was a saga of toil, sweat, blood and tears, the prototype of many martyrs after him. When even Pundits and great political leaders faltered in proclaiming our ideal of absolute political independence, Vasudev Balwant openly proclaimed it. He was the first Indian leader to go from village to village to preach the mantra of swaraj and to exhort the people to rebel against foreign rule."

A Latent Anger

Vasudev’s roots trace back to Shirdhon, near Panvel, where he was born on November 4, 1845. Even as a boy, he had a fiery spirit. Pune-based historian Mohan Shete shares a family story: "His paternal grandfather Anantrao was the last commander of the fort of Karnala, which was lost when the Peshwas were defeated by the East India Company in 1818. When Vasudev was still a child, his grandfather would carry him to the fort on his shoulders and narrate stories of war, the deeds of legendary warriors and the losses inflicted by the British." Those tales planted seeds of defiance in young Vasudev.

He traveled to Mumbai and Pune for his studies and, in 1862, became one of the early graduates of Bombay University. Soon after, he worked in British offices like Grant Medical College and the Commissariat Examiner’s Office in Mumbai. Today, a statue carved from a single rock stands at Aadya Krantiveer Vasudev Balwant Phadke Chowk in Dhobi Talao, Mumbai, honoring his time there and symbolizing his unbreakable resolve. In 1865, his bosses sent him to Pune with a glowing recommendation for promotion. He joined the Military Finance office under the Controller of Military Accounts.

In Pune, Phadke settled in Sadashiv Peth, then a quiet outskirts area surrounded by thick forests. Historian Shete recalls, "In the evenings, people used to be afraid to venture to this side." At this point, Phadke wasn’t yet a revolutionary, though he harbored a growing anger toward the British. He worked in the cantonment and lived with his wife, Saibai, with whom he had a daughter. After Saibai’s death in 1872, he married Gopikabai in 1873. Shete explains Phadke’s shift: "By now, he was becoming a revolutionary. He taught Gopikabai to read and write as well as wield swords, fire guns and ride horses in the surrounding forests. These were activities that men practiced, but to make one’s wife do it, and in a Brahmin household, was radical. Vasudev’s thinking was that his wife should be able to fight if there was war with the British."

|

Taking up Arms Against the British

Vasudev Balwant Phadke’s life in Pune took a sharp turn as events pushed him toward rebellion. On a personal level, he was furious when his British bosses denied him leave to visit his dying mother. A year later, they refused again when he asked for time off to perform her first death anniversary rituals. These rejections stung deep, lighting a fire in him against the colonial rulers.

Around this time, Pune was buzzing with new public groups where people could talk about the country’s troubles. One such group was the Sarvajanik Sabha, and its lectures changed Phadke’s thinking. Historian Mohan Shete explains, "During this time, a number of public organisations were coming up in Pune, such as the Sarvajanik Sabha where people could discuss the state of the country. Lectures by Justice Madhavrao Ranade and Dadabhai Naoroji about the British draining India of its wealth and resources made a great impact on Phadke. After listening to them and reading their lectures in newspapers, Vasudev was convinced that they needed to fight the British. An armed revolution was the only way forward." Hearing how the British were stripping India bare fueled his anger. He started to see that words alone wouldn’t free his people—action was needed.

Another big influence was Lahuji Raghoji Salve, a teacher who didn’t just train people in weapons but also stirred their love for the motherland. Shete adds, "Salve was another reason Vasudev’s resolve was strengthened to fight the British." Salve’s students included big names like Tilak and Mahatma Phule, but for Phadke, this training was personal. It hardened his will to take on the British with force. By now, he was ready to give everything to the freedom struggle. He sent his wife, Gopikabai, back to her family’s home so he could focus entirely on the fight ahead.

Phadke also wanted to inspire the younger generation. In 1874, he teamed up with Waman Prabhakar Bhave and Laxman Narhar Indapurkar to start the Poona Native Institution. Unlike British-run schools, this place was all about teaching kids to love their country. Shete notes, "To impress young minds, Phadke, with Waman Prabhakar Bhave and Laxman Narhar Indapurkar, had set up the Poona Native Institution in 1874. Unlike British schools, the Poona Native Institution would inculcate a love for the motherland among children." That institution still stands today as the Maharashtra Education Society, running 75 schools and colleges with about 40,000 students and over 2,000 staff members (source: Maharashtra Education Society official site). For Phadke, it was a way to plant seeds of rebellion in young hearts, preparing them for the battles to come.

1870 – Public Agitation and the Aikyavardhini Sabha

By 1870, Vasudev Balwant Phadke was deeply involved in Pune’s growing push against British wrongs. He joined a local movement to let people voice their anger about life under colonial rule. That same year, he started the Aikyavardhini Sabha, which means “Society for Unity.” This group was all about teaching young Indians to love their country and come together to fight for it. Through this youth club, Phadke and his friends worked hard to tell people about India’s struggles and figure out ways to fix them. It was like planting the first seeds for a big stand against the British.

Then, Phadke took his message to the Deccan region, a place hit hard by drought and ignored by the British. He traveled around, talking to villagers about Swaraj—self-rule. His trips weren’t just about words; he was calling people to act, to dream of a free Indian republic. This was a big deal because a terrible famine was hurting the area, and the British didn’t seem to care. Families were suffering, and Phadke’s words gave them hope. He also started protest speeches in 1875, gathered about 300 men from poor and overlooked communities, and led them in raids and fights. For a short time, he even took control of parts of Pune, showing he was serious about kicking the British out.

|

Make in India, Buy Indian (1874 – Establishing a National School)

Phadke believed India needed to stand on its own, a idea he called Swadeshi. In 1874, he helped set up one of the first national schools in Pune, later called the Bhave School under the Maharashtra Education Society (MES). This school wasn’t run by the British—it was made to train Indians to help their own country. Phadke promised to use only things made in India, like Khadi cloth, because he thought true freedom meant not depending on foreign goods for anything—money or culture.

Historian Mohan Shete shares, "In a letter, he asks the youth to become entrepreneurs and industrialists because the war against the British would not be fought with arms alone. The country needed to create products so that Indians did not use foreign-made goods." Shete also says that since Phadke took the Swadeshi vow, everything he wore or used came from India. In his book Vasudev Balvant Phadke: First Indian Rebel Against British Rule, historian VS Joshi writes, "He was a pioneer in many respects." Joshi points out that way back in 1879, Phadke dreamed of an Indian Republic, a dream that came true 68 years later in 1947. For Phadke, making and buying Indian was a way to fight back.

1875 – Protest Speeches After Baroda’s Gaekwad Deposed

In 1875, the British kicked out Maharaja Malhar Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, saying he was a bad ruler. This made Phadke and many Indians furious. He hit back with loud, fiery speeches, calling out the British government for their actions. He wasn’t shy—he openly talked about Swaraj, or self-rule, when even big leaders were afraid to say it out loud. Phadke went from village to village in the Deccan, telling people to join hands and fight the foreigners. After the 1857 revolt, he was the first to openly push for an armed attack to overthrow the British.

His words were bold and clear. He wanted everyone to know that India could only be free if the people stood up together. Traveling those dusty village roads, he became a voice for the angry and the hopeful, lighting a spark that others would follow.

1878 – Open Calls for Rebellion

Even while working secretly, Phadke kept stirring things up in Pune. People back then said he’d run through the streets, banging a metal thali to call folks together. Then he’d stand up and shout, "Our country must be free… The Englishmen must be driven out." On Sundays and holidays, he’d head to nearby towns like Panvel, Palaspe, Tasgaon, and Narsobachi Wadi, talking to villagers and soldiers about rising up. These trips were some of the first real political campaigns by an Indian back then. Crowds came to listen, curious and excited, and his words "created waves,"' though they didn’t start a big fight right away.

By late 1878, Phadke saw that speeches alone weren’t enough. He stopped relying on public talks and turned to building secret plans for a real armed rebellion. He knew the time for just words was over—action was next.

1877–1878 – Secret Organizing and Armed Training

Phadke didn’t get much help from educated city folks or gentle reformers, so he looked to the rural poor instead. With his teacher Lahuji Raghoji Salve—a wrestler from a low caste who ran a training spot in Pune—Phadke gathered 200 to 300 men from groups like the Ramoshi, Koli, Bhil, and Dhangar. These were tough, working people ready to fight. He taught them to ride horses, shoot guns, and swing swords, turning them into a hidden guerrilla army for India’s freedom. At night, under the cover of wrestling matches and youth meetups, his team also sang patriotic songs and shared funny verses mocking the British around Pune.

This wasn’t just about fighting—it built a "public culture of patriotism" long before leaders like Tilak or Lajpat Rai came along. By late 1878, Phadke had a secret network ready to hit the British hard.

1876–1877 – Deccan Famine Relief and Awakening

The Deccan famine of 1876–77 broke Phadke’s heart. He saw peasants starving and dying while the British did almost nothing. He traveled through the famine-hit areas, sometimes in disguise, to see it all for himself. The hunger and sickness he witnessed shocked him. In his diary, he wrote, "Thinking day and night of this and a thousand other miseries, my mind was bent upon the downfall of the British power in India. I thought of nothing else. The idea haunted my mind. I used to rise in the dead of night and ponder over the ruin of the British until at last I almost became mad with the idea."

That suffering and the British coldness convinced him—only by throwing out the British could India stop such disasters. It made him even more determined to plan an armed revolt.

|

February 20, 1879 – Formation of Phadke’s Rebel Army

The rich folks ignored Vasudev Balwant Phadke’s pleas for help with guns or cash. Frustrated, he wrote in his diary, "Means do not by themselves matter. If the rich men do not voluntarily contribute the funds for swaraj, why not forcibly deprive them of their wealth to swell the coffers of swaraj?" Since the educated upper class wouldn’t back him, he turned to the poor and forgotten communities. He put together a group called the “Ramoshi,” teaming up with tribal and lower-caste people to widen his fight. It all kicked off on the night of February 20, 1879. Phadke gathered his closest friends—Vishnu Gadre, Gopal Sathe, Ganesh Deodhar, Gopal Hari Karve, and others—at a quiet spot near Loni, about 8 miles north of Pune. There, they started their militia. Around 200 armed men swore to battle for India’s freedom, likely making it the first proper revolutionary army in modern India. Phadke admitted they’d have to do “dacoities”—raids like bandits—to pay for their war. He told his crew, "The time for leaving home to join the struggle had come… We shall secure many more weapons and much more money after our first raid. We shall fight against the police and the Government." That secret meeting under the stars launched his bold uprising against British rule.

February 23, 1879 – First Raid at Dhamari

Just three days later, on February 23, 1879, Phadke’s band struck. They hit the village of Dhamari in Shirur taluka, Pune district, aiming for the house of a moneylender named Balchand Faujmal Sankla. This guy had just collected tax money for the British. Phadke’s men took down the guards and grabbed about ₹400 in cash. They also set fire to the account books and debt papers of greedy bankers in the village. Phadke shared the money with starving villagers hit by famine, showing this wasn’t just theft—it was for the people. Still, the British quickly labeled him a “dacoit,” or bandit, for it. Now a wanted man, Phadke had to keep moving, staying with poor villagers who hid him because they admired his guts.

March–April 1879 – Guerrilla Raids Across Pune District

Through early 1879, Phadke kept up his fight in Pune’s countryside. His group hid in forests, like near Nanagaon, where locals sheltered them. They picked targets—rich landlords who sided with the British or government cash stashes—and attacked fast. Before each raid, they cut telegraph wires, broke railway tracks, and stopped mail coaches to keep the British in the dark. In March and April, raids around Shirur and Khed talukas brought in money to feed hungry peasants and arm his team. Phadke made a strict rule: "No women or children were to be harmed" during these raids—they had to stay honorable. Word of his Robin Hood-style attacks spread like wildfire. Newspapers called it “the revolt of Vasudev Balwant,” stirring excitement that maybe a new rebellion was brewing in the Deccan. The British got worried and stepped up their hunt for him, but to the locals, he was becoming a hero.

May 10–11, 1879 – Raid on Palaspe and Chikhali (Konkan)

By May 1879, Phadke took his fight to the Konkan coast. On the night of May 10–11, a team led by Ramoshi chief Daulatrao Naik hit British treasury posts at Palaspe and Chikhali, near Panvel. They pulled off a huge haul—about ₹1.5 lakh—in a well-planned attack. Loaded with cash, they headed east toward the Western Ghats. But the British were hot on their trail. Near Ghat Matha in Maval, Major Henry Daniell’s troops caught up. A fight broke out, and on May 11, Daulatrao Naik was shot dead. Losing his right-hand man was tough, and the British took back most of the money in the ambush. Short on supplies and under pressure, Phadke had to flee south, ending his free run in the Pune-Konkan area.

|

May 1879 – Phadke’s Revolutionary Proclamation

Even after that loss, Phadke didn’t back down. In late May 1879, while hiding, he sent out a manifesto challenging the British. He blasted their harsh taxes and bad rule, blaming them for India’s poverty, and promised they’d pay a heavy price. He mailed copies to the Governor of Bombay, district collectors, and other British officials. At the time, the British had put a ₹4,000 reward on his head. Phadke fired back with his own “reverse bounty,” offering ₹5,000 to anyone who could nab the Governor, Sir Richard Temple, plus rewards for catching or killing British officers. He signed these as "The New Pradhan of the Peshwa", calling back to Maratha glory and hinting he led a rebel government. He stuck these notices on Pune’s walls, warning of a big revolt like 1857. It caused a stir—The Times of London even wrote about the “Phadke phenomenon” on June 3, 1879, pushing the British to fix their ways (source: British Newspaper Archive). Indians were thrilled by his daring at a time when most leaders just begged the British politely.

June 1879 – Flight to Shri Shaila Mallikarjuna (Srisailam)

With the British closing in, Phadke fled to Hyderabad state. By mid-1879, he and a few followers reached the Shri Shaila Mallikarjuna temple in Srisailam, Kurnool district, Andhra Pradesh—a holy Shiva site in a thick forest. It meant something special; his hero, Chhatrapati Shivaji, had been there too. At Srisailam, a worn-out Phadke stopped to rest and think. On April 25, 1879, he finished the second part of his diary, asking India’s people to forgive him for not winning yet. Feeling his end might be near, he wanted to give his life there for the cause, but the priests said no. This hideout was a low point—tired, short on men, and unsure—but he left determined to try one last time.

June–July 1879 – Attempting to Reignite the Revolt

In early summer 1879, Phadke roamed Hyderabad State, gathering about 500 mercenaries—Rohilla Pathans, Sikhs, and Arabs from the Nizam’s army—with promises of loot. He dreamed of uprisings beyond Maharashtra, sending messengers to rally rebels far away and planning to mess up British communications everywhere. In a letter, he wrote of sending teams "so that the mails would be stopped and the railways and telegraph interrupted, so no information could go from one place to another", then breaking open jails to free prisoners for his army. He hoped a small spark would set off a huge rebellion. But the British, led by Hyderabad’s Police Commissioner Abdul Haque and Major Daniell, tracked him nonstop. His big plan stayed mostly a dream—he ran out of time.

July 20, 1879 – Betrayal and Capture at Devar Navadgi

The end came in late July 1879 when one of Phadke’s own turned him in for the reward. On July 20, while resting at a temple in Devar Navadgi, near Kaladgi (now Bagalkot, Karnataka), British troops surrounded him. A fierce fight broke out, but Phadke was overpowered and caught alive. The months-long chase was done. The British were thrilled to nab western India’s most wanted rebel, whose actions had almost sparked a new resistance in 1879. At 33, his capture crushed his followers’ spirits. Some villages mourned him like a lost hero.

September 1879 – Trial in Pune and Life Sentence

After his capture, Vasudev Balwant Phadke was brought back to Pune under tight security to face trial for fighting the British Crown. The trial happened in the Pune District Sessions Court near Sangam Bridge in late 1879. Even though he was seen as an outlaw, Phadke got a lawyer—Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi, a famous nationalist known as “Sarvajanik Kaka,” who stood up for him in court. The British brought strong proof against him, like his diary and letters that showed his plans to rebel. In court, Phadke spoke from his heart, saying, "Day and night, there is but one prayer in my heart, Oh God, even if my life be lost, let my country be free, let my countrymen be happy. I have taken up arms, raised an army and rebelled against the British Government with this single aim. I could not succeed. But, some day, someone will succeed. Oh my countrymen, forgive me for my failure." The British judge didn’t waver—Phadke was found guilty of treason and robbery against the government. In late 1879, he was sentenced to life in exile, meaning he’d be sent far away to a prison for good. He and a few of his remaining friends were locked up in Pune until the British could ship them out. Outside the court, crowds gathered when the verdict came. They were sad but cheered loudly for Phadke’s bravery, seeing him as a hero for India’s freedom.

Early 1880 – Deported to Aden Jail

Once sentenced, the British hurried to get Phadke off Indian soil. In early 1880, they put him on a ship to Aden prison in the Aden Settlement, now Yemen. This tough, fortress-like jail was far from home and held other political prisoners the British feared too much to keep in India. Phadke was cut off from his country, locked up in a strange land under rough conditions. He stayed there for about three years. Even though he got sick with tuberculosis and his rebellion had failed, his spirit didn’t break—he kept looking for a way to be free again.

February 13, 1883 – Daring Escape Attempt

On the night of February 13, 1883, Phadke made one last bold move. He tried to break out of Aden prison. Using the same cleverness that had troubled the British back in India, he worked the door of his cell off its hinges and slipped out into the dark. For a short moment, the 37-year-old tasted freedom outside those walls. But it didn’t last—guards noticed he was gone and caught him not far from the jail. His health was weak by then, but his will wasn’t. Even though the escape didn’t work, it showed he’d never just sit quietly under British rule.

February 17, 1883 – Martyrdom by Hunger Strike

After being caught again, Phadke decided he’d rather die than stay a prisoner forever. He started a hunger strike in Aden jail, saying no to all food. He held on for days, getting sicker and weaker. On February 17, 1883, Vasudev Balwant Phadke passed away in captivity, worn out by hunger and illness. He was only 37. The British said he died of tuberculosis made worse by fasting, but really, Phadke chose death as his final stand against them. Back in India, his sacrifice hit hard—freedom fighters in Maharashtra and beyond called him a martyr.

Phadke’s Legacy in Pune and Beyond

In Pune, others picked up where Phadke left off. The Chapekar brothers, who lived near Sadashiv Peth, killed WC Rand, the Plague Commissioner, in 1897 because of his harsh ways during the plague. Anagha Bedekar, Treasurer of the Aadya Krantiveer Vasudev Balwant Phadke Smarak Samiti in Mumbai, which looks after a museum in Shirdhon and a memorial in Mumbai, says, "In Shirdhon, every school has a picture of the pioneering freedom fighter and he still fills them with a love for the country." Historian Mohan Shete takes students to Narsingh Temple and asks, "I tell them to think of a pillar or a wall that we are striking with a hammer. If after 100 blows, the wall cracks and falls, were the previous 99 blows in vain? I would say the first blow was most important because it was struck when you couldn’t see success in the end. In that darkness, it was Vasudev who lit the first flame of freedom when the country was discouraged after the failure of 1857. He was also the first non-royal to lead a revolt, paving the way for leaders such as Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi, who came from ordinary homes unlike the leaders of 1857. Hence, Phadke is significant in history."

His fight lasted less than a year, but it lit a spark. A 2004 Parliament booklet said, "When even pundits and great political leaders faltered in proclaiming the idea of absolute political Independence, Vasudev Balwant openly proclaimed it" and "paved the way for organized armed movement for freedom." His spirit lived on in secret groups and fighters like the Chapekar brothers and Bhagat Singh, earning him the name “Father of the Indian Armed Rebellion.”

|

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- "When all other rights are taken away, the right of rebellion is made perfect": Revolutionary Sachindra Nath Sanyal, whom Gandhians sought to crush was the one to form Army of the Republic of Hindustan (1924), an Indian army that overthrew the British Raj

- "Yogi seemed to be doing everything wrong, yet everything came out right": Story of an Unknown Hindu Yogi from the annals of freedom fights, who with a muscular build, sitting on a leopard skin killed a British Captain in front of the British Army in 1857

- Our first true war of independence lie forgotten within the fog of time and tomes of propaganda: Sanyasi Rebellion, when "renouncers of the material world" lead peasants in revolt against British and fundamentalist islamic clans

- "Victory are reserved for those warriors who are willing to pay it's price": One of the greatest and undefeated General Zorawar Singh conquered Laddakh, Tibbat,Gilgit, Skardu, Baltistan and defeated army of Imperial Chinese Tibetans in Dogra-Tibetan War

- Hero of Pawankhind: Veer Maratha Bajiprabhu Deshpande, who led 300 Soldiers against 12000 Adilshahi Army defending Shivaji

- "Tied to the cannon and blown to pieces couldn't deter his loyalty to Ettayapuram King and his devotion to the motherland stood sturdy and unshaken": Veeran Azhagumuthu Kone, Tamil Warrior who rebelled against Britishers 100 years before 1857 war

- “In warrior’s code, there’s no surrender, though body says stop… spirit cries, never!”: Fierce warrior queen Naiki Devi rode into battle of Kasahrada with her son on her lap, leading soldiers in a fierce counter defeating Ghori to never return to Gujrat

- In just 8 years, a forgotten warrior carved through Ladakh, Baltistan, and even Tibet with 6,000 men—his name was General Zorawar Singh, and though he fell in 1841 at Toyo, his sword drew the borders we still live by; a hidden tale buried in Himalayan ice

- Taimur was attacked and defeated by 20 year old Rampyari Gurjar and her army of 40,000 women

- Unsung Heroine Pritilata Waddedar, Who Shook The British Raj at the age of 21

- Film based on Nathuram Godse ‘Why I killed Gandhi’ gets opposition from Congress party demanding to ban the movie in Maharashtra, Cine Workers Association seek nationwide ban

- Add Vedas and review freedom fighter's portrayal in School textbooks: Parliamentary Committee on Education

- "Purify your hearts with the water of love of motherland in national temple, and promise that millions will not remain untouchables, but brothers and sisters": Swami Shraddhanand, who awoke Hindu consciousness

- "बावनी इमली": In 1858, at Bawani Imli in Fatehpur, 52 revolutionaries led by Jodha Singh Ataiya were brutally hanged from a tamarind tree by the British, a forgotten chapter of India's freedom struggle buried under decades of silence and neglect

- Remarkable return to Uttar Pradesh of Dr. Gita Patel, a Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's descendant, embraces the state's good governance under Aditya Yoginath, she ushers in a groundbreaking revolution in cancer treatment, shaping a brighter future for UP