MORE COVERAGE

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

"It is through an unbroken chain of witnesses that we come to see the face of reality": The first ever recorded nose surgery was done by Sushruta who is also regarded as the father of surgery, wrote one of the world's earliest works on medicine & surgery

Sushruta has been regarded as one of the pioneers of surgery. He performed procedures with crude surgical instruments that paved the path for today's operations. However, his existence is shrouded in myth and mystery. Sushruta belonged to a rich heritage of learned scholars and practiced and taught surgery at Benares University around 600BC.

His work is assembled into a monumental thesis, possibly the first text book on surgery, the ‘Sushruta Samhita’ where he describes surgical instruments, procedures, illnesses, medicinal plants and preparation, dissection and the study of human anatomy, embryology and fractures. Sushruta is perhaps best known for the nasal reconstruction flap which is still used in different versions. For all his contributions, he has been aptly titled ‘Father of Plastic Surgery’.

|

Nasal Amputation

…cutting off the nose is a special way of manifesting vengeance. Of all the organs of the body, the nose is considered to be the organ of respect and reputation. - Shah Tribowandas (1889, India)

The specialty of plastic surgery traces its roots back to the barbaric practice of nasal amputation. As far back as 3000 BC, there is evidence that nasal amputation existed as a form of punishment. The Hindu poem Ramayana (1500 BC), depicted on the walls of Angkor Wat, refers to how the Sri Lankan princess Surpunakha will undergo nasal reconstruction after she suffered nasal amputation.

Mass nasal amputations as a war punishment occurred in Nepal in 1767. Kirtipur, a town within the Kathmandu Valley, had repeatedly resisted invasion from the mountain and warlike Ghurka people. When Kirtipur fell, the Ghurka King, frustrated with such a voracious defense, ordered the nasal amputation of all 865 males, sparing only those not yet weaned or those who played wind instruments. The city was later referred to as Naskatapoor, or the ‘city without noses.’

Nasal amputation persists to this day. In 2010, Time Magazine featured Bibi Aisha, a young Afghan girl who in an attempt to escape her husband was captured, only to have her nose and ears amputated

With the historical frequency of this practice, a demand grew in India for a solution. The human barbarity of nasal amputation was to be met with human ingenuity.

|

Indian Method

First the leaf of a creeper, long and broad enough to fully cover the whole of the severed or clipped off part, should be gathered, and a patch of living flesh, equal in dimension to the leaf should be sliced off from down upward, from the region of the cheek and after scarifying [the margins] with a knife, swiftly adhered to the severed nose. - Sushruta (600 BC)

Sushruta recorded the Ayurveda (Science of Life) in the Samhitas sometime between 1000 and 600 BC. He focused on the surgical arts, describing surgical instruments, preparation, indications, postoperative care, and techniques. Sushruta writes, ‘Surgery has the superior advantage of producing instantaneous effects by means of surgical instruments and appliances. Hence, it is the highest in value of all the medical tantras.’ As the first to describe nasal reconstruction, he is referred to as the ‘Father of Plastic Surgery.’

Sushruta described many principles of nasal reconstruction still in use today. He emphasized the importance of a template, in this case a leaf, to appropriately size the defect. Preparation of the recipient wound bed is highlighted so as to accept the flap. Stenting of the nostrils with hollow tubes or reeds will ‘facilitate respiration and prevent the adhesioned flesh from hanging down’, reiterating the difficulty of managing circumferential cicatricial forces. Sushruta focused on the importance of nasal proportion, writing, ‘the adhesioned nose should be tried to be elongated where it would fall short of its natural and previous length or it should be surgically restored to its natural size in the case of the abnormal growth of its newly formed flesh.’ In the 600s, Vagbhata described folding the flap to provide nasal lining.

The art of nasal reconstruction was secretly passed down through generations of three families in the region of India and Nepal. They were among a caste of potters and bricklayers. The Kanghiari family of Khanga (in Punjab) was known to practice the art since AD 1440, keeping a patient registry and requiring signed consent. Sons were taught along with daughters-in-law, but unmarried daughters were not permitted to learn so that if they married, the craft would not escape the family. The precise timing of the transition to the forehead flap as the predominate Indian Method of rhinoplasty remains obscure.

|

First Nosejob in Modern Human History

During the third Anglo-Mysore war in 1792 between the East India Company and Tipu Sultan of Mysore, Cowasjee, a Parsi bullock-cart driver and four other British soldiers were taken prisoner by Sultan at Seringapatam, Karnataka.

In a truly barbaric Islamic way, their noses were cut off before releasing along with their amputated noses as a mark of humiliation. For nearly a year, these soldiers went without a nose until Sir Charles Warre Malet, a British minister in the Peshwa court at Poona, came across an oilcloth merchant with a feeble scar on his nose.

The merchant explained that his nose had been amputated as a punishment for adultery and was later rebuilt by a Poona potter using his forehead skin. The oilcloth merchant could never have predicted that his disclosure would spark a chain of events that would establish the “Hindu method” as the gold standard of nose reconstruction worldwide.

Sir Charles summoned the potter recommended by the oil-cloth merchant to reconstruct the noses of Cowasjee and the other four soldiers. This nasikasadhana art had been practised in complete secrecy and passed down from generation to generation within a single family. Cowasjee’s forehead flap nasal reconstruction, on the other hand, was witnessed by Mr. Tho Cruso and Mr. James Findlay, two British physicians from the Bombay Presidency. After the operation, the patient was required to lie on his back for 5-6 days. On the 10th day, bits of soft cloth were put into the nostrils to keep them sufficiently open. The procedure was always successful, and the new nose almost resembled the natural one. After a while, the scar on the forehead was no longer visible.

Note: An unknown Maharatti healer reconstructed his nose with a forehead flap, and this was witnessed by two English physicians of the East India Company, Mr. Thomas Cruso and Mr. James Frindlay. They described this remarkable surgery in 1793, in the Madras Gazette newspaper in Bombay. Within a year, the news about this procedure arrived in London. In a letter to the editor of the Gentlemen's Magazine, author ‘B.L.’ described Cowasjee's reconstruction, how wax was used as a template and forehead skin was transposed… ‘leaving undivided a small slit between the eyes. This slit preserves the circulation until a union has taken place between the new and the old parts’ Although the European medical community took notice, it was Joseph Constantine Carpue who pursued the Indian Method with vigor. Carpue studied the reports, interviewed army personnel from India, and practiced on cadavers. In 1814, he became the first European to perform the Indian Method on a patient who had lost his nose to syphilis. After removing the dressings three days later he exclaimed ‘My God, there's a nose!’ Carpue's text in 1816 helped to spread the technique through Europe and America. |

Cowasjee’s portrait depicting the successful surgery was painted ten months later, in January 1794, by the British painter James Wales. In March 1794, the copper portrait appeared in Bombay. The news was published in the Madras Gazette on 4 August 1794, and in October 1794, in a letter to the editor of The Gentleman’s Magazine, Sylvanus Urban described “a very curious chirurgical procedure” of “affixing a new nose on a man’s face” that was unknown to civilised Europeans what had been practised for generations in uneducated India.

In January 1795, the surgical procedure was published as “A Singular Operation,” and Cowasjee’s portrait appeared alongside the article. In April 1795, The Courier published an article titled “Account of the method of supplying artificial noses as practised by the natives of the Malabar coast”, claiming supremacy of the Indian method. After a detailed discussion with Lieutenant Colonel Ward (Cowasjee’s commanding officer), J.C. Carpue, a British surgeon, successfully used this method on two patients in 1814 and published his paper in 1816. The procedure became widely popular in Europe as the “Indian Method,” but not the Hindu Method. Despite many modifications since then, the procedure has stood the test of time and is still the best method of nose reconstruction today.

The publication of the nasal reconstruction in The Gentleman’s Magazine and later by Carpue laid the foundations for modern plastic surgery. The “Indian Method” became popular all over the world, kindled the interest of the Western world, and brought recognition to India as the birthplace of plastic surgery.

|

The first principles of plastic surgery were articulated by Sushruta in his treatise Sushruta Samhita in 600 BCE and translated into Arabic by Ibn Abi Usaibia in the 11th century, travelling far into Arabia, Persia, and Egypt; however, the Western world became aware of it much later. Susruta described over 300 surgical procedures and about 120 surgical instruments (all his own inventions). He also talks about 385 plant-generated, 57 animal-generated and 64 mineral-generated medicine.

Medicines were produced in the form of Powders, distillates, decoctions, mixtures, gels. He talks of 24 kinds of swastiks, 2 kinds of sandas (pliers), 28 types of needles and 20 kinds of catheters. Sushruta gave a description of 14 kinds of bandages besides the six bone dislocations and 12 kinds of fractures of bones. His book also talks about 28 diseases related to the ear and 26 connected to the eyes.

While Cowasjee was immortalised in British publications, paintings, and engravings. the surgeon whose skills gave Cowasjee a nearly normal nose went unnoticed. Through this, the British attempted to prove to the world that they took good care of their soldiers. By concealing the name of the surgeon, they made sure that India did not get its due recognition.

The case is significant because it is one of the few in medical history where the patient is more popular than the surgeon. However, the event still managed to enable the rightful recognition of India as the origin of plastic surgery and the restoration of its honour. Unlike today’s plastic surgery, it was never about superficial cosmetic surgery in ancient India. It was always about treating serious deformities.

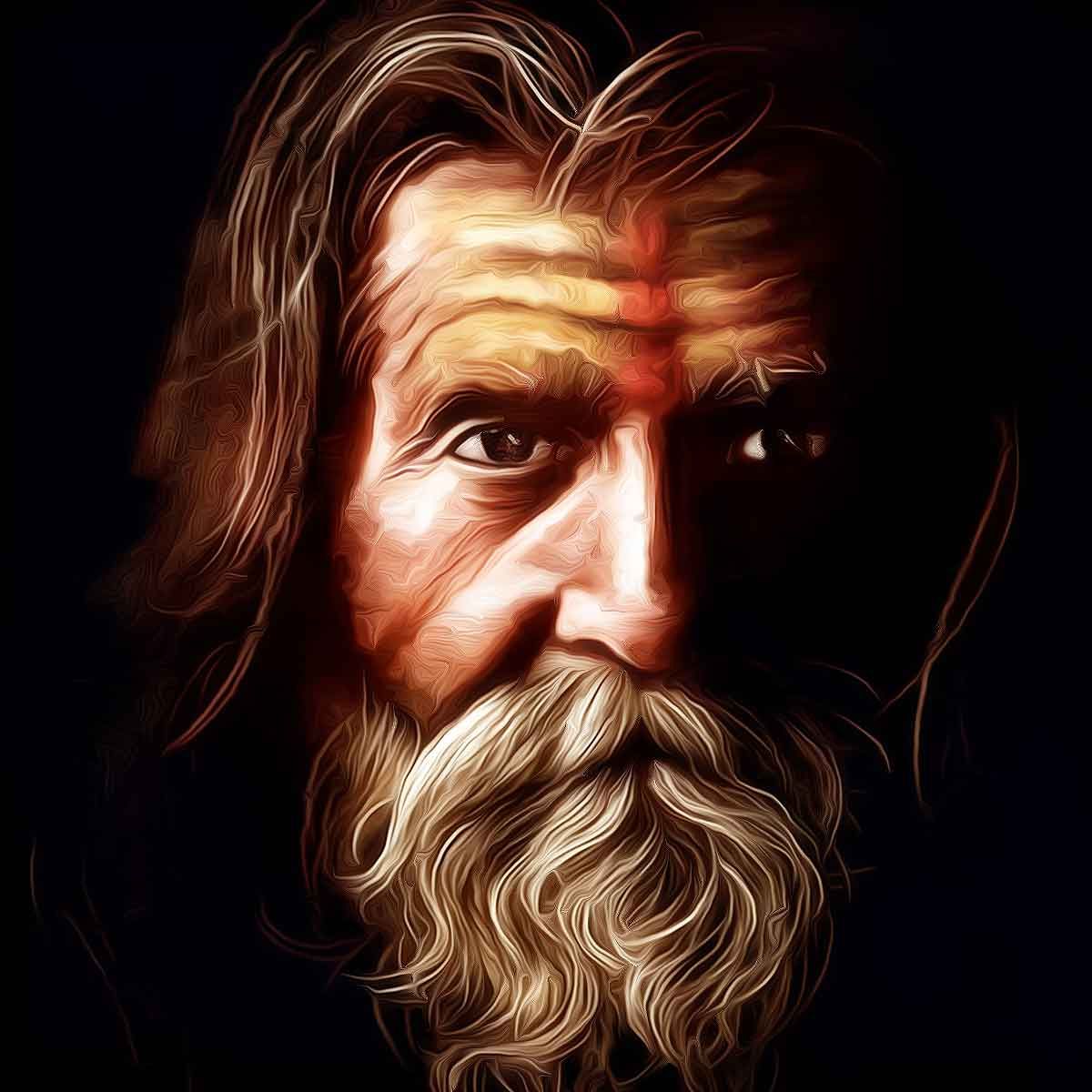

Even today, Indian vaccines, like Covishield, continue to save crores of people around the world. Attached image is of Cowasjee after surgery by James Wells.

References:

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- "Where is all the knowledge we lost with information": Father of Surgery - World`s First Surgeon was Maharishi Sushruta who performed surgeries on nose, ears, bladder, cataracts, fistula, joints, and hemorrhage more than 2600 ago with surgical instruments

- "When we bring what is within out into the world, miracles happen": Built by the Rajput king Sawai Jai Singh II in 1734, UNESCO World Heritage site Jantar Mantar, Jaipur is an astronomical observatory, which features the world’s largest stone sundial

- “Genius is never understood in its own time”: Do you know when you put your debit card in ATM and ask for money, machine arranges the money before giving it to you using Srinivasa Ramanujan’s partition theory, celebrated as National Mathematics Day

- "You are what you believe in. You become that which you believe you can become": J Robert Oppenheimer, a theoretical Physicist recited a quote from Bhagavad Gita after witnessing first Nuclear explosion - "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds"

- "Varahamihira - ancient Astrologer, Astronomer and Mathematician": His encyclopaedic knowledge and lively presentation of subjects, as dry as astronomy, made him a celebrated figure, discovered trigonometric formulas and Pascal’s triangle

- "Three things cannot long be hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth": It was not Isaac Newton but Rishi Kanad who first discovered "Laws of Motion" at least 2000 years before Newton in his Vaishesika Sutras, was also known as "Father of Atomic Theory"

- Legend of Maharishi Charaka also known as The father of Ayurveda: Earliest school of medicine known to mankind is Ayurveda

- "Neglect will drive a noble mind to depart for another land": Brilliant mind - Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay who created India's first and world's second test tube baby 'Durga' in 1978 with the help of some general equipment and refrigerator was punished for it

- "You are what you believe in. You become that which you believe you can become": Google Software Engr. launches GitaGPT that deploys AI to answer your questions about life problems, “What if you could talk to Bhagavad Gita? To Lord Krishna himself?”

- "Culture is the widening of the mind and of the spirit": Origin of the timepiece AM and PM - Arohanam Martandasaya means the ascension (rise) of the sun, Patanam Martandasaya means the inclination of the sun

- "Truth will ultimately prevail where there is pains taken to bring it to light": We studied that speed of light was discovered by Ole Roemer (1676), well in reality Rig Veda contains the accurate speed of light in one of its shlokas thousands of years ago

- "Sanskrit is the language of philosophy, science, and religion": A Neuroscientist, James Hartzell explored the "Sanskrit Effect" and MRI scans proved that memorizing ancient mantras increases the size of brain regions associated with cognitive function

- "Sringara Prakasa - Sanskrit poetry": Classical theater, dancers (Bharatanatyam, Odissi, Mohiniyattam) refer to Sringara as 'the Mother of all rasas, one of the nine rasas, usually translated as erotic love, romantic love, or as attraction or beauty

- "Symbols are powerful because they are the visible signs of invisible realities": Real Sindoor comes from a tree, a low-height tree that finds mention in our scriptures. Seeds from the tree are crushed to make fine powder and were used by Sita and Hanuman

- "Its a desirable thing to be well-descended, but the glory belongs to our ancestors": An artist from Pakistan went viral for using artificial intelligence to reimagine life in Mohenjo Daro, one of the most striking monuments from the dawn of civilization