Sanatan Articles

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar – A Misunderstood Legacy

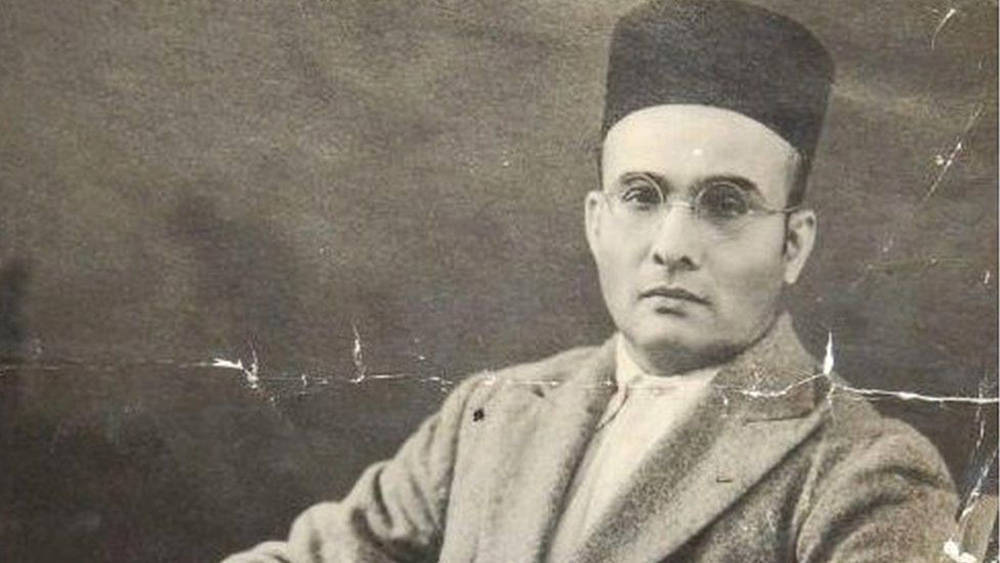

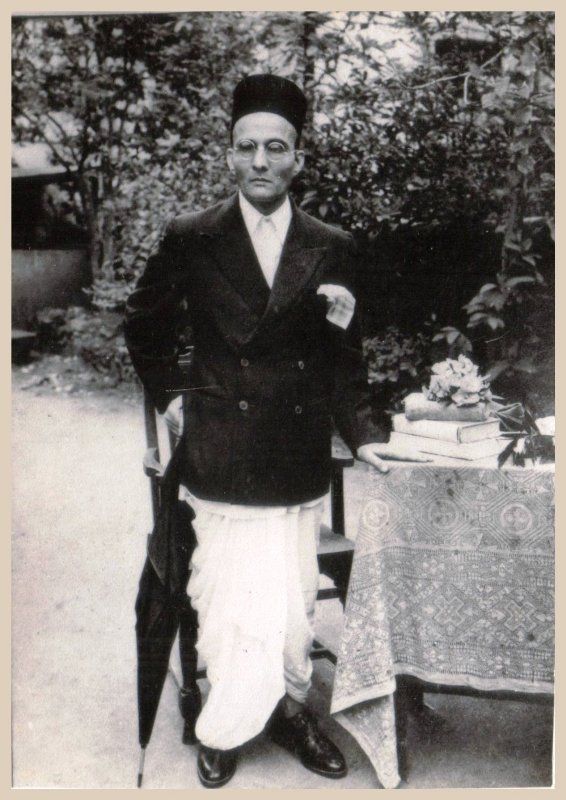

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was a versatile personality who has been a source of inspiration for generations of Indians. He was a committed revolutionary, renowned freedom fighter, eminent political thinker, devoted social and religious reformer, prolific writer and poet, and a rationalist philosopher. He was, as the epithet aptly describes, a brave and die-hard patriot. His love for the Motherland runs through all facets of his personality - from a valiant freedom fighter, to enthusiastic social reformer, to prolific writer, to fiery orator.

Early days

Shri Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was born on 28 May 1883 at Bhagur, a village near Nasik. His parents, Shri Damodarpant and Smt. Radhabai belonged to a middle-class family. He joined the village school at the age of six. Vinayak grew up listening to passages read out by his father from the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana and Ballads and Bakhars on Maharana Pratap, Chhatrapati Shivaji and the Peshwas. He was a voracious reader and read any book or newspaper from cover to cover, page to page. An inborn genius that he was, Savarkar had a rare talent in poetry and his poems were published by well-known newspapers when he was hardly ten.

In 1893, when he was ten years old, Savarkar engaged in his first militant activity in an event which foreshadowed his future as a champion of the Hindu cause. According to his biographer Keer, in response to communal riots between Hindus and Muslims in the (then) United Provinces and Bombay (today’s Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, respectively),

The boy Savarkar led a batch of selected schoolmates in a march upon the village mosque. The battalion of these boys showered stones upon it, shattered its windows and tiles and returned victorious…The victory, however, was not allowed to go unchallenged. The Muslim school-boys gave battle to Vinayak, the Hindu Generalissimo. Although the number of his soldiers decreased at the time of joining the battle, Vinayak routed the enemy with missiles like pins, penknives and thorns…

It is probable that Keer exaggerates this episode in order to provide a compelling image of Savarkar as a patriotic hero from birth, but it is also likely that some such event took place, indicating, from a very young age, the commitment Savarkar felt to defending his fellow Hindus.

The assassination of two British Plague Commissioners by the Chapekar brothers in Poona on 22 June J897 and the subsequent execution of Damodarpant Chapekar dIsturbed the young Savarkar. He took a vow in front of Godess Durga, of sacrificing his nearest and dearest, to fulfil the incomplete mission of the martyred Chapekar. He vowed to drive out the British from his Motherland and to make her free and great once again.

In 1901, Savarkar married Yamunabai. They had three children-two daughters and one son. One of the daughters died in her infancy.

Earlier in 1899, when he was just 16 year's old, Savarkar formed Mitra Mela, a group whose principal aim was to attain the complete political independence of India. The name of the group was later changed to Abhinava Bharat. Hundreds of young men joined the organisation. Savarkar urged his countrymen to despise everything that was English and to abstain from purchasing foreign goods. On his inspiration, many students daringly performed bonfire of foreign clothes.

Not averse to the idea of armed revolution, if required... Savarkar justified action saying: ''You rule by bayonets and under these circumstances it is a mockery to talk of constitutional agitation when no constitution exists at all ... Only because you deny us a gun, we pick up a pistol."

Savarkar excelled in his academic career as well and with recommendations of Lokmanya Tilak and Shivrampant Paranjpe he applied for scholarship to study at India House – a hostel for Indian Students in London run by Shyamji Krishnavarma, who encouraged a decidedly anti-British attitude among his mentees.

He left for London in 1906 and continued his mission there also.

|

Savarkar in London

Soon after his arrival at India House, Savarkar took charge of the Indian Home Rule Society, changing its name to the Free India Society – a more transparent announcement of the group’s opinions and aims. For Savarkar, this group was likely an opportunity to take the ideals, and some of the same members, of the Abhinav Bharat, and transition them into a more modern, European form. In 1907, just a year after his arrival in England, Savarkar took over complete leadership of India House when Krishnavarma fled to Paris over concerns that he might be arrested for statements made in his publications.

In 1907, when the anniversary of the Indian Rebellion in 1857 was celebrated in London as a victory of the British over the rebels, Savarkar wrote and circulated an extremely patriotic pamphlet titled “Oh Martyrs,” which lauded the bravery and sacrifice of the Indian leaders instead. The leaflet was yet another opportunity for Savarkar to showcase his impressive rhetorical skills, and it quickly became notorious, attracting the attention of both British and Indian police. In one fiery excerpt, which gives a good idea of the tone of the author, Savarkar writes:

We take up your cry, we revere your flag, we are determined to continue that fiery mission of ‘away with the foreigner,’ which you uttered, amidst the prophetic thunderings of the Revolutionary war. Revolutionary, yes, it was a Revolutionary war. For the War of 1857 shall not cease till the revolution arrives, striking slavery into dust, elevating liberty to the throne.

|

Strategy for national liberation

According to Savarkar, the liberation of the Motherland was to be achieved by a preparation for war which included the teaching of Swadeshi and boycott of foreign goods; imparting national education and creating a revolutionary spirit; and carrying patriotism into the rank of the military forces.

With clear indications of an imminent war in Europe, Savarkar and his Abhinaua Bharat started writing, printing, packing and posting revolutionary literature. He wanted to impart military training to his comrades.

A resolution demanding Swaraj was unanimously passed at a Conference held in December 1908. Conscious of the hardships that could follow, Savarkar warned his audience: "Before passing this resolution, just bring before your mind's eye the dreadful prison walls, and the dreary dingy cells".

Mustering international support

Savarkar was among the first Indian leaders who realised the importance of international support for India's freedom struggle. The Indian revolutionaries of Abhinaua Bharat were in constant touch with the revolutionary forces of Russia, Ireland, Egypt and China.

Savarkar's aim was to organize a united anti-British front with a view to rising in revolt simultaneously against the British Empire. Savarkar wrote articles on Indian affairs in the Gaelic America of New York, got them translated into German, French, Italian, Russian and Portuguese languages and had them published. Savarkar deputed Madame Cama and Sardar Singh Rana to represent India at the International Socialist Congress which was held on 22 August 1907 at Stuttgart in Germany. He had also been a staunch supporter of the idea of the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine. He won the sympathies of the Irishmen serving in Scotland Yard, who actually helped the Indian revolutionaries in smuggling political literature.

Savarkar gained both fame and increased police surveillance in 1909 when he published his now infamous book, The Indian War of Independence of 1857. This work was a re-interpretation of the 1857 event which was characterized by the British as, first and foremost, a military mutiny that soon grew to a widespread civil rebellion in the Hindi-speaking region of the North.

One of the Indian students living in London and attending Savarkar’s lectures was Madan Lal Dhingra, who – on July 1, 1909 – shot and killed William Curzon-Wyllie, a prominent India Office official, at a party held by the National Indian Association. It was this act that was the eventual undoing of Savarkar, who was found by the police to be a primary conspirator in the assassination.

The assassination of Curzon-Wyllie rocked London, a city that had previously seen no outright violence from the Indian students living in its midst. Though British police forces had been steadily increasing surveillance up to 1909, the attitude of the government towards Indians, overall, was still relatively lax.

Police had been hoping to pin down Savarkar for a number of years. He had been writing and distributing revolutionary pamphlets since his arrival in England, as well as assisting in the smuggling of weapons and books back to India, there had been little concrete evidence with which to arrest him under the more liberal laws of Great Britain, and the government was forced to bide its time until an opportunity presented itself.

Curzon-Wyllie’s assassination proved to be just such an opportunity, as well as a catalyst for how Indian students were to be treated in England. Many Londoners were horrified that such an act of violence could have been committed under the noses of the British police, and the relatively lenient attitude that had been so far adopted towards India House and Indian students, in general, came under intense criticism.

Clearly, during this period of his life, Savarkar was still most strongly dedicated to the Indian independence fight, viewing the enemy as the British Empire. His commitment to freedom at all costs isolated him from a large majority of both British officials and Indian leaders. Most prominently, he loudly disagreed with the message of Mahatma Gandhi, who – in the same period – was developing his nonviolence movement.

After Dhingra’s arrest, Savarkar and the other members of India House attempted to keep a low profile, recognizing the danger they were in. In late 1909, Savarkar – following in the footsteps of his mentor, Krishnavarma – moved to Paris to join a group of expatriate revolutionaries. On March 13, 1910, however, he returned to London and was arrested as he stepped off the train. The charges against him, reproduced by John Pincince from the original Times article on the subject, were as follows:

The first charge was framed under the section which made it an offence, punishable by death or transportation for life, to wage war against the King or to abet in so doing; and the property of any offender might be forfeited. To wage war or to abet the waging of war against the King in India was nearly but not quite equal to the offence of treason in England. The legal definition of war did not necessarily mean war in an ordinary sense, but any over act to subvert the Government. The second charge… [was] an offence to conspire to deprive the King of the sovereignty of British India or any part of it. The third charge was for collecting arms or ammunition or otherwise waging war against the King. The fourth charge was based on another section… which made it an offence for a person to utter or write any words and make any signs or visible representations with intent to bring into hatred or contempt, or to excite disaffection against the Government of India… The fifth charge was for abetment of murder.

Because laws in Britain during the early 20th century were far more lenient than those of India, the Indian government strongly desired Savarkar’s trial to take place in his home country. In order to achieve this, one of the primary charges against him – sedition – was derived from a publication he had written in Pune before leaving India for London. As a result, under the Fugitive Offenders Act of 1881, the Indian government was able to charge him for his crimes, and despite his best efforts to avoid it, Savarkar was extradited to Bombay for his trial in July of 1910. In India he faced two trials which took place over the course of 1910-1911, resulting – finally – in his conviction and a sentence of two life terms in the Cellular Jail at the Andaman Islands.

The truth is that, although he strongly believed in using violent means if pacific ones failed, Savarkar never committed any violence, himself. His danger, therefore, lay in his use of words. As an excellent speaker and an extremely convincing writer, Savarkar posed the largest threat to the Indian government through his speeches and – more importantly – his writings, which were continually smuggled into and throughout India. Even once it jailed him, however, the government could not stymy the revolutionary’s voice.

Savarkar composed and wrote his most famous and controversial work, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? while interned in both the Cellular and Ratnagiri Jails between 1910-1923. Though at first glance Hindutva appears to be a dramatic shift away from the political issues Savarkar had addressed in the years before his arrest, a closer reading of the work reveals it to be tackling many of the same issues. The difference between Hindutva and Savarkar’s pre-prison writings lies, rather, in the author’s fascinating evolution from young, fiery revolutionary to shrewd and mature intellectual.

|

His arrest and extradition

While his extradition on the 08th July 1910, when the ship was anchored at the Marseilles port, he took a courageous decision and took permission from the security personnel to use the toilet. After taking permission he closed the door tightly and covered the glass of the toilet with help of his clothes. There was a window in the toilet which opened towards the huge ocean.

After measuring the dimension of the window and his own body, Savarkar ji jumped into the ocean. Since he didn’t come back for a long time, the security personnel banged the door of the toilet and subsequently broke it, but the bird had already escaped. When security personnel looked into the ocean, they found out that Savarkar ji was swimming towards the port of France.

They called their team and started firing bullets. Few soldiers took a small boat and started following him, but Savarkar ji swam with a lightning speed and reached the shore. He surrendered to the French police and asked for political asylum.

Since he was aware of the international laws, he knew that he had not committed any crime in France. So, the French police can arrest him but cannot extradite him to any other country. That’s why he took this courageous step. He declared himself independent once he reached the shores of France. Meanwhile, the British police also reached there and demanded the return of the prisoner. Savarkar ji quoted the international law regarding extradition.

Also, arrival of a foreign citizen on French land was a crime. British police bribed the French officials. Unfortunately, French police succumbed to their pressure. Therefore, they handed over Savarkar ji to the British police. Now, he was put under strict surveillance and was handcuffed along with chains around his body.

Influenced by world-wide public opinion in favour of him, the French Government demanded that Savarkar be returned to France. However, the Hague International Tribunal passed a judgment in favour of the British Government. At the young age of 27, he was sentenced to two transportations for life and imprisoned in Andamans. The life in prison (1911-1924) was one of untold hardships.

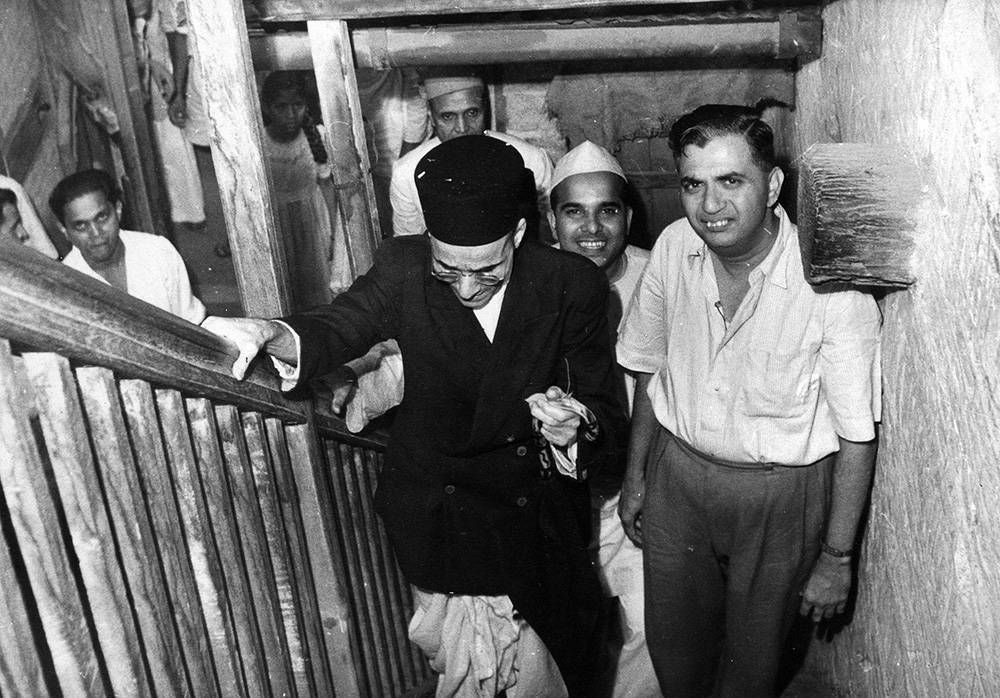

The cell which housed Veer Savarkar |

The Prison Years

In July of 1911, Savarkar was transported by train from Thane Central Jail in Maharashtra to Madras, where he – along with a group of fellow prisoners sentenced to transportation – boarded a boat destined for the Cellular Jail at Port Blair in the Andaman Islands.

Due to its location, as well as the extreme isolation and dehumanization prisoners encountered within its walls, Port Blair’s Cellular Jail was reserved primarily for those convicts assigned to the lengthiest and most severe sentences.

On arriving in Port Blair for the first time, Savarkar and the other convicts are met by the infamous prison superintendent, David Barrie. Savarkar quotes the warnings issued by Barrie:

“I would give you one more tip,” and it is this: “You will be involving yourself in a terrible mess if you ever try to run away from this place. The prison is surrounded on all sides by vast, dense, impenetrable jungles; the cruelest of aborigines make their abode in them; they are cannibals. If they catch you, they kill you, and make a meal of tender, young bodies like yours; as easily as we may eat cucumbers!”

Once Savarkar reaches the prison, he finds that all the warders of political prisoners were Muslim because a Hindu warder may be kind towards other Hindu. Hence the authorities put upon Mussalman warders who reported Hindu’ss movements to them in an exaggerated form, or invented stories about them…”

At the same time that Vinayak Savarkar was interned at Port Blair, his brother was also an inmate there. Ganesh Savarkar (also known as Babarao), Vinayak’s older brother, was an ardent revolutionary like his younger sibling. He had been deeply involved in the freedom movement within India, itself, and was arrested for leading a rebellion against British rule.

The prisoners became fed up with the conditions in the Cellular Jail and with watching their friends suffer and be punished. As a result, a number of work strikes were taken up, and it appears that Savarkar was often at the lead of these. Mr. Barrie declared that “Savarkar was the father of unrest in the Andamans…” His involvement in numerous inmate demonstrations during his time in jail reveals Savarkar’s commitment to his causes, even under the most trying circumstances.

While in jail, he studied all of the religious books that he could get his hands on. Among these were the Christian Bible and the Muslim Koran. In Chapter Two of Part II of “My Transportation”, Savarkar addresses the issue that provides, perhaps, the greatest motivation for the development of his anti-Muslim rhetoric later in life. It delves into the massive issue of forced conversions. It is here that Savarkar writes, “I was sent to the Andamans in 1911, and I soon found out that some Hindu prisoners had been converted to Islam and assumed Muslim names after their transportation.” He goes on later in the paragraph to question:

How strange it is, then, that…the Pathan and other Mussulman warders, petty officers and jamadars of that prison could convert the Hindu prisoners to I slam, by methods of conversion and coercion. Leave alone the prisoners who knew by their age what they were doing. But what of lads of tender age who were so forcibly converted to Islam by their Muslim warders? Is it not the duty of the British officers to care for their spiritual welfare as it is their care to look after their physical and moral well-being?

Although it is true that he submitted a number of petitions, and even repudiated his revolutionary past, it is a mistake to vilify Savarkar for such actions. Savarkar openly acknowledges, within My Transportation for Life, both the petitions that he sent as well as the discussion that he had with members of a Commission sent by the British Government to investigate conditions at the Cellular Jail. In a section of the conversation that he quotes within the pages of his memoir, Savarkar is addressing a plea for constitutional reforms,

stating, “The constitutional reforms will enable me to do some constructive work for the country. And I would try to do my work in a constitutional manner. If the reforms prove fruitful that way, and clear the path to the goal all have in view, a political revolutionary like myself will prefer that path to bloodshed and unnecessary murder.” Far from hiding his compliance with the British Government, Savarkar – on this occasion – is openly suggesting his willingness to cooperate if certain aims are met.

Savarkar was transported from Port Blair to Ratnagiri Jail on the mainland in 1921. He remained in Ratnagiri Jail for another two years before he was provided with a probationary release, under which terms he was required to remain in Ratnagiri and refrain from all political activity until 1937.

|

Savarkar and Gandhi

In 1923, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? was published for the first time. Only two years later, Savarkar’s The Story of My Transportation for Life began appearing in serialized form in the magazine Kesari. Kesari, a Hindu Nationalist publication was originally founded by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a man widely viewed as the father of Hindu nationalism – especially in his home province of Maharashtra.

Savarkar’s passion for his country and ardent devotion to his cause attracted the attention and admiration of many other young Indian nationalists of the period. No surprise, then, that Gandhi likely viewed this recently released Marathi-intellectual as a rival and threat, especially since the two held such opposing views with respect to a number of issues including the treatment of Indian Muslims. It is a widely known fact that Gandhi, in attempting to create a unified India, went to great lengths to woo his nation’s Muslim population – even declaring open support for the Khilafat Movement. This support is voiced within My Experiments with Truth, where he writes:

It was not for me to enter into the absolute merits of the [Khilafat] question, provided there was nothing immoral in them. In matters of religion, beliefs differ, and each one’s is supreme for himself… Friends and critics have criticized my attitude regarding the Khilafat question. In spite of the criticism, I feel that I have no reason to revise it or to regret my cooperation with the Muslims. I should adopt the same attitude, should a similar occasion arise.”

Another moment in Gandhi’s Collected Works, from more than a decade later, continues to show the tension between the two men. In 1939, in a letter to a friend, Gandhi revealed his frustration with Savarkar and his compatriots. The issue, this time, was a statement issued by Savarkar and Ambedkar, along with a number of other leaders, claiming that the Muslim League and National Congress, combined, “did not represent the whole or even the bulk of India and that any constitutional or administrative arrangement arrived at between …[them] could not be binding on the Indian people.”

As Gandhi notes in his letter, “I have tried to woo him and his friends. I have walked to Savarkar’s house. I have gone out of my way to win him over. But I have failed.” Clearly, although the dissent may never have risen to a head in public, the 1920’s and 30’s were not a time of amiable friendship between these two opposing leaders, and Gandhi may well have sought some method of fighting back against Savarkar’s publicized and quite radical right-wing ideas.

Despite Savarkar’s best efforts, however, the 1930’s and 40’s were dominated by the National Congress, which managed to maintain popular support largely through the emblematic figure and unmatched political manoeuvring of Gandhi. The death knoll of Savarkar’s political career was the murder of Gandhi in 1948, for which he was arrested and placed on trial. Despite numerous and damning ties that were revealed between himself and Nathuram Godse, the assassin, Savarkar was acquitted in February 1949. Even after his acquittal, however, Savarkar’s image never recovered from the implication, and – to this day – his memory is inextricably linked with the notorious event.

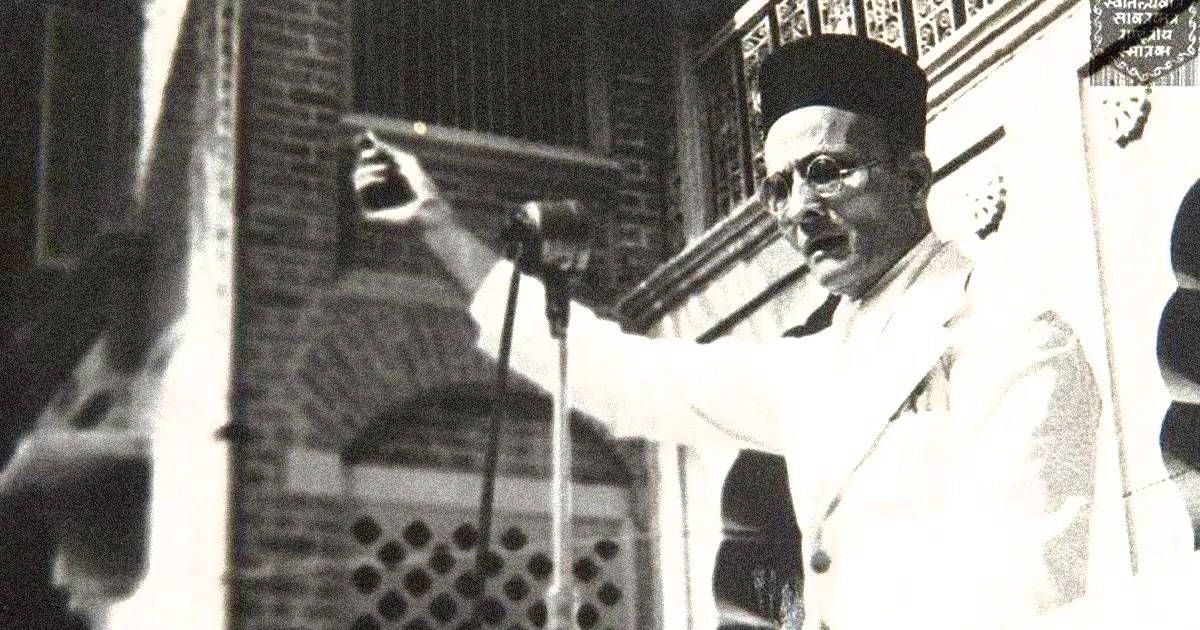

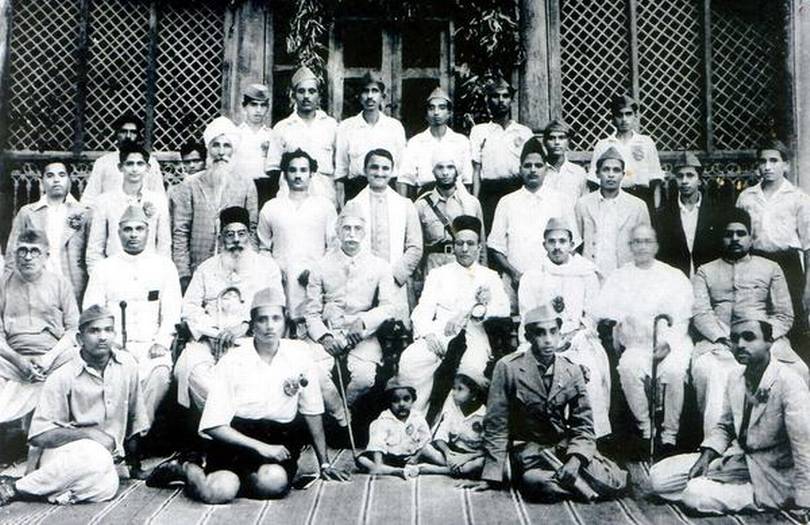

1944- VD Savarkar (seated fourth from right) after addressing a State-level Hindu Mahasabha Conference in Shivamogga. Photo- The Hindu Archives |

Savarkar's dream state

Savarkar was of the view that a nation is a group of mankind which is bound together by some or all of the common ties such as common religion and culture, common history and traditions, common literature and consciousness of common rights and wrongs, occupying a territory of geographical unity, and aspiring to form a political unit. Savarkar was for Hindu-Muslim unity and visualized a non-sectarian State.

In his Presidential Address at the Hindu Mahasabha Session in 1937 at Ahmedabad, Savarkar declared:

Let the Indian state be purely Indian. Let it not recognise any invidious distinctions whatsoever as regards the franchise, public services, offices, taxation on the grounds of religion and race. Let no cognizance be taken whatsoever, of man's being Hindu or Mohammedan, Christian or Jew. Let all citizens of that Indian State be treated according to their individual worth irrespective of their religious or racial percentage in the general population. Let that language and script be the national language and script of that Indian state which are understood by the overwhelming majority of the people as happens in every other state in the world, that is, in England or the United States of America and let no religious bias be allowed to tamper with that language and script with an enforced and perverse hybridism whatsoever. Let 'one man one vote' be the general rule irrespective of caste or creed, race or religion.

Savarkar's vision of India was one in which all citizens would have equal rights and obligations irrespective of caste, creed, race or religion, provided they avow and owe an exclusive and devoted allegiance to the State. All minorities were to be given effective safeguards to protect their language, religion, culture, etc. but none of them would be allowed to create a State within a State or to encroach upon the legitimate rights of the majority.

Further, the fundamental rights of freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, of worship, of association, etc. were to be enjoyed by all citizens alike. In the event of any restriction imposed, the interest of public peace and order or national emergency would be the guiding principle. There would be joint electorates and 'one man one vote' would be the general rule. Services would go by merit alone. Primary education would be free and compulsory. Nagari would be the national script, Hindi, the lingua franca and Sanskrit, the Devabhasha of India.

After his release from jail in 1924, Savarkar took up the task of social reform with full earnestness. He waged a war against casteism and untouchability and fervently wrote against the taboos regarding inter-caste marriages, sea-crossing and re-conversion. Savarkar fearlessly and whole-heartedly supported Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's struggle for liberation of the 'untouchables'.

Savarkar, the rationalist

Savarkar's outlook was absolutely modern, scientific and secular. He wrote: "Let an earthquake occur, public prayer is our remedy. Let a patriot fall ill, we go to attend a crowded prayer meeting. Let a pestilence ravage our land, and we kill goats in sacrifice to ward off the calamity. It was quite all right when we did not know the causes of such things, but to stick to these superstitions even when science has revealed the cause of such calamities are simply absurd." He wanted to promote the principles of science in every activity of human life.

His literary achievements

Savarkar's literary works were marked with vigour, sublimity and idealism. His poetic qualities were evident in the following verse which he recited in one of his melancholy moments in London:

"Take me O Ocean! Take me to my native shores. Thou promised me to take me home. But thee coward, afraid of thy mighty master, Britain, thou has betrayed me. But mind, my mother is not altogether helpless. She will complain to sage Agasti and in a draught he will swallow thee as he did in the past".

Being deeply influenced by the philosophy of Guissepe Mazzini, Savarkar translated his autobiography into Marathi. The impact of the bookwas such that the book suffered proscription for forty years. While in the Cellular Jail in Andamans, in the absence of any writing material, he etched his poems on the walls of his cell. The collection of his poems are aptly named as Wild Flowers. Though complete in themselves, Kamala, Gomantak, Saptarshi, Virahochhvas and Mahasagara are parts of the incomplete epic.

His other poems, Chain, Cell, Chariot Festival of Lord Jagannath, Oh Sleep, and On Death Bed have a philosophical basis. Savarkar's renowned work Hindutva was written in Ratnagiri jail under his pen-name Mahratta. The book defines the principles of Hindu nationalism at length. During his internment at Ratnagiri, he wrote another of his famous books, Hindu Pad-Padshahi.

Savarkar's book The Indian War of Independence, 1857 became the source of inspiration for many revolutionaries. The book was proscribed even before it was published. Savarkar managed to get the book printed in Holland. It later reached India, America, Japan and China wrapped in covers with fictitious names. Leaders of the Ghadar Party, drawing inspiration from the book, raised the Komagatamaru Rebellion. Bhagat Singh and his colleagues brought out an underground edition in 1928.

According to N.C. Kelkar, "All the writings of Savarkar are like leaps through arches fixed with knives and blazing torches turned inside." The book Savarkar worked the longest on was Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History which has nearly a thousand references. He also wrote My Transportation for Life, Hindu Rashtra Darshan, An Echo from Andamans, and the novels Moplah Rebellion and Transportation.

|

An inspiring revolutionary

Towards the later years of his life, Savarkar's health deteriorated fast and he was almost confined to bed. He repeatedly requested doctors not to prolong his life. From 3 February 1966, he began his fast unto death. To the surprise of doctors, he survived for twenty-two days with little or no medicine, taking only five or six tea-spoonfuls of water every day. Ultimately, on 26 February 1966, at the age of 83, he breathed his last.

Shri C. Rajagopalachari once described Savarkar as a national hero, a symbol of courage, bravery and patriotism, an abhitirth in the long battle for freedom. In his tributes on the passing away of Veer Savarkar, the then President Dr. S. Radhakrishnan said that Savarkar was "a steady and sturdy worker for the Independence of our country ... his career was for many a youngster a legendary one."

The then Vice·President Dr. Zakir Husain paid tributes to Veer Savarkar and said: "A great revolutionary as he was, he inspired many young men to work for the liberation of our Motherland". Paying rich tributes to Savarkar, the then Prime Minister, Smt. Indira Gandhi said: "Savarkar was a great figure of contemporary India and his name is by·word for daring and patriotism. He was cast in a mould of a classic revolutionary and countless people drew inspiration from him".

Veer Savarkar's life has always been and will ever remain an inspiration to generations of Indians.

|

Savarkar’s Legacy

Without a doubt, in the thirty years between his death and the re-birth of the Hindu Nationalist movement – in the form of the BJP – Savarkar’s image underwent a massive change. During his lifetime Savarkar was associated most strongly with his time as a young freedom fighter, and then later as president of the Mahasabha and possible accomplice in the murder of Gandhi.

The importance of his tract, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? was largely overshadowed by other, more public, aspects of his life. Since 1990, however, the ideas of Hindutva have re-emerged more prominently than ever, and Savarkar is being recognized far more widely for his work. In fact, there have been new editions of Hindutva published every two years since 1999, an indicator of the continued relevance and popularity of the tract.

In an opinion piece from The Caravan in 2014, which cites a statement made in August by RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat: “Hindustan is a Hindu nation. Hindutva is the identity of our nation. There are different communities in it. And such is its strength that it can incorporate these other communities in itself.” The fact that this statement drew no criticism from Modi has angered many Indians who perceive the prime minister as slowly moving the nation towards the ideas of Hindutva, and away from the secularism it has embraced for the past seven decades.

References:

Swatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar - G.C. MALHOTRA, Secretary- General, Lok Sabha

https://arisebharat.com/2019/07/18/the-historic-jump-of-vinayak-damodar-savarkar/

A Misunderstood Legacy: V.D. Savarkar and the Creation of Hindutva – by Julia Kelley-Swift Class of 2015

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Calcutta Quran Petition: A petition to ban the Quran altogether was filed 36 years ago, even before Waseem Rizvi petitioned for removing 26 verses from Quran

- Our first true war of independence lie forgotten within the fog of time and tomes of propaganda: Sanyasi Rebellion, when "renouncers of the material world" lead peasants in revolt against British and fundamentalist islamic clans

- A Great man Beyond Criticism - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- When Secular Nehru Opposed Restoration Of Somnath Temple - The Somnath Temple treachery

- Godse's speech and analysis of fanaticism of Gandhi: Hindus should never be angry against Muslims

- Kartar Singh Sarabha - The Freedom fighter who was Hanged at the age of 19 and inspired Bhagat Singh

- Father of the Nation! Absolutely not. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was not the father of the nation either officially or otherwise

- Moplah Genocide of the Malabar Hindus, 1921: Thousands of Hindus slaughtered

- If not for Muslim appeasement, Vande Mataram would have been India's National Anthem: the history of Muslim opposition and support

- Northeast is not the Part of Pakistan because of 'Netaji': Subhas Bose and the ‘special’ case of Assam

- Theft on a Grand Scale - Britain stole $45 Trillion from India and lied about it. Indian money developed Britain and Other Countries

- Nehru lost election and became first Prime Minister of free India: All thanks to miraculous Gandhi

- Why Hindus not claiming their temples back from the Government control: Is pro-Hindu govt will always be in power

- Nehru's Himalayan Blunders which costed India dearly - Integration of Princely States

- Anuj Dhar claims that Subhas Chandra Bose was suspected of being ‘poisoned’ after ouster from the post of Congress president