Sanatan Articles

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

Our first true war of independence lie forgotten within the fog of time and tomes of propaganda: Sanyasi Rebellion, when "renouncers of the material world" lead peasants in revolt against British and fundamentalist islamic clans

I first came across the Sannyasi rebellion not in the books of history (thank you ridiculous education system) but in a scary tome of literature that I would never have voluntarily opened on my own. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s 1882 novel, “Anandamath” (Abbey of Bliss) is a 336 page long tribute to these heroes of the Indian independence movement that the rest of the country seems to have forgotten. The novel is otherwise famous for publishing our national song, “Vande Mataram” and sparking the first kindles of nationalism in a heavily subjugated population. Vehemently banned by the British government upon its publication, it only came back in print after 1947, long after the author’s death.

Bankim himself was born almost a hundred years after the Sannyasi rebellion. Given that there was no internet (duh), or any semblance of documents that would archive dissident’s voices, it was a near miracle that he got to hear of this story because that memory had been carefully wiped from the public’s memory by the Raj who feared that it might inspire patriotism in the minds of people. And boy were they right! For when Bankim’s novel went to press and people got to read about how a motley of untrained and unarmed wayfaring travelers stood up to the might of the British Empire, it struck a hungry flame of imagination that eventually culminated in the glorious struggle for independence.

|

Bankim’s grand uncle lived up to the princely age of 108 and it is he who told the little storyteller about the fiercely courageous fighters who fought to death their right live. Bankim grew up to give his childhood heroes the ultimate tribute in the form of “Anandamath”, ensuring that their sacrifices be forever honoured and cherished by the people they fought for. Yet how easily we have forgotten them again.

India is the land of spiritual identity where people’s freedom is considered the ultimate spiritualism. To live this spirituality, we Indians have paid a great price due to which we are still able to continue the only surviving ancient civilization. To pay this price, even the saints had to draw arms against the mighty and cruel colonial powers of the British. Come, I will tell you a tale like none you have ever heard.

It is a 40 year war, waged relentlessly by poor peasants led by sanyasis clad in Bhagwa. It is a forgotten war, obscured by time and malicious history. It is a war ‘India’ refuses to remember. But we owe it to our patriots and to our unborn generations that this story be told, their sacrifices, remembered & the patriots respected.

Contrary to common historical narrative, 1857 was NOT Hindustan’s first war of independence from British rule. The first true war of independence was a 4 decade long war fought between 1763-1800 by the SANYASIS – sadhus & saints of Bengal. This war shook the new born British empire to its core & extracted a horrific price in blood from the new rulers of Hindustan.

But was the sanyasi revolt a new revolt? Or was it a continuation & expansion of an ongoing revolt against the last ruling islamist Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud Daula? To answer this question let us look further back into the past. Let us go to that period in time when Siraj ud Daula ascended the throne (masnad) of Bengal. In 1756, Siraj ascended the throne upon death of his maternal grandfather, Alivardi Khan. While Alivardi Khan’s reign was marked by a grudging acceptance of all faiths within it borders, Siraj was cast in a different mold. He was greatly influenced by hardline islamists like Shah Waliullah and upon his ascension he let loose a reign of terror so brutal that in 1 year the Hindus of Bengal sought help from Jagat Seth Mahtab Rai who in turn petitioned and financed the British to overthrow the despot nawab. But during the years before Siraj’s rise to power his jihadists beliefs had already alienated a number of Hindu subject who had risen in revolt.

The sadhus and sanyasis have for long been regarded as men of authority and in these sanyasis, the downtrodden, oppressed Hindus sought leadership. The peasants and working class Hindus were already up in revolt against the jihadist marauders of the nawab. Victory of British brought no respite and the oppression of the people only became widespread and pervasive.

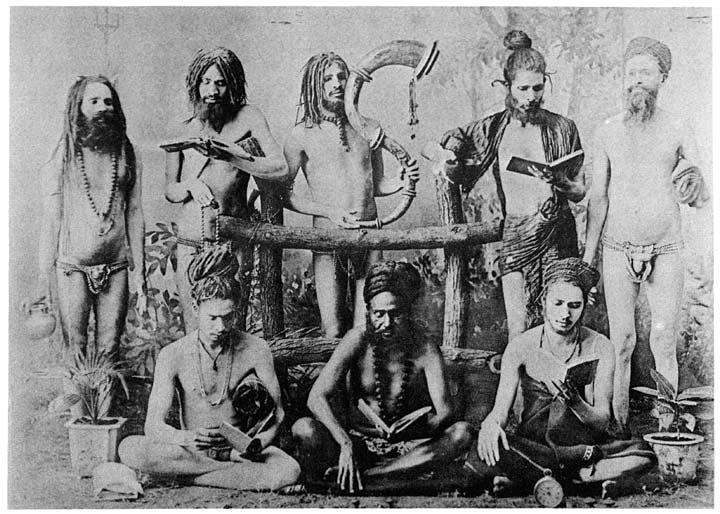

This is a picture of a group of saffron wearing sanyasis who led a revolt against British. "Sanyasi rebellion" predates Gandhi, Nehru by 150 years. - By Trueindology |

Sannyasis

The sannyasis of the eighteenth century descended from the ten branches, of the Adwaita school which Shankaracharya and his disciples had started in the ninth century. They were known as the Dasnami orders. According to Matthew Clark, these ten groups of Dasnamis were divided up into four monasteries, located in Dwarka, Jagannath Puri, Badrinath and Srngeri. It is believed that Shankaryacharya placed his major disciples as heads of four great maths. Clark added that in ethnographic accounts the Dasnami gossains were treated as mendicants as well as priests, bankers, traders, farmers and mercenaries. Therefore, they had a complex relationship with their social environment.

These men were named after the group of monks, Giri, Puri, Bharati, Ban, Aranya, Parbat, Sagar, Tirtha, Ashrama, Saraswati. Out of the ten names, the Tirthas, Ashramas, Saraswatis, Bharatis, were called dandis and the rest were called gossains. These gossains abandoned celibacy and took up religious and professional activities. The gossain is also the name for heads of Vaisnavabairagis, Ramanandi order and the followers of Vallabhacharya. It is also clear from Bhabananda Goswami, a character from the book Anandamath and a sannyasi rebel, that the sannyasis used to take vows of celibacy. This could allude to Nagas’ vows of celibacy. Mahendra also refers to a character by the term gossain (Chattapadhyay 1938). According to Farquhar, the sannyasis were usually non-violent and were prohibited from using violence by their vows of ahimsa (Farquhar 1925:482-483). It is believed that in the sixteenth century when the Muslim fakirs took part in wars and killed sannyasis, the government chose to remain neutral. As a result, no one got punished. The sannyasis could not retaliate because of their vows of non-violence. Eventually, the government had to step in and protect them (Farquhar 1925:482-483). However, J.N. Sarkar believed that the

Dasnami sects had originated long before Akbar’s reign. The Dasnamis had two distinct sub-sects - theological (shastradhari) and fighters (ashthradhari).

However, their activities often overlapped. For instance, the “Naga Sannyasis” were skilled fighters (Sarkar 1984:90). William Pinch observed that there is an ‘ethical claim’ to the oral tradition that the sannyasis and yogis were initially non-violent, and they turned violent in response to Muslim aggression. He agreed with Sarkar that these men were armed long before the Mughals came into the picture.

These sannyasis were not particularly poor as they were involved in economic activities such as trade with Nepal and usury. Even the Persian sources such as Tarikh-i-Ahmadshahi and Marathi sources like Prithwi Gir, Gosavi Vatyacha Sampradaya demonstrate that the sannyasis were quite active in parts Northern India, Punjab and Gujarat since the Mughal period.

|

They acted as traders as well as money-lenders in those areas (Rose 1991:303-304). They were also called the vagrant race, traders and spies. Bernard Cohn has also commented on the trade relations and the role of gossains. (Cohn 1964: 176-177) According to J.N. Sarkar, the sannyasis deposited their earnings with the common fund of the 'Maths' from which the gurus and mahants would advance money to the chelas (disciples) to carry on trade and other economic activities. The akharas were the warehouses of arms and weapons and produced fighters to combat enemies. The Atal and Avahan akharas produced various ‘legends’ during the latter Mughal period. There appears to be ambiguity regarding the status of wandering and travelling sannyasis within the akharas. Sarkar opined that even the majority of the wandering sannyasis belonged to the akharas.

The three harbingers of Doom

Sannyasis would travel to North Bengal to visit shrines and sites of pilgrimage there. This was a tradition predating hundreds of years, if not more. During their travels, it was customary for them to collect a sizeable amount of alms from the local landlords. Usually, the zamindars had no problem paying, and collecting this money was an amicable transaction. But after the consecutive battles of Plassey and Buxar, when Bengal effectively began to be ruled by the British and the Nawab remained merely a figurehead, things changed drastically.

|

1. The British East India Company

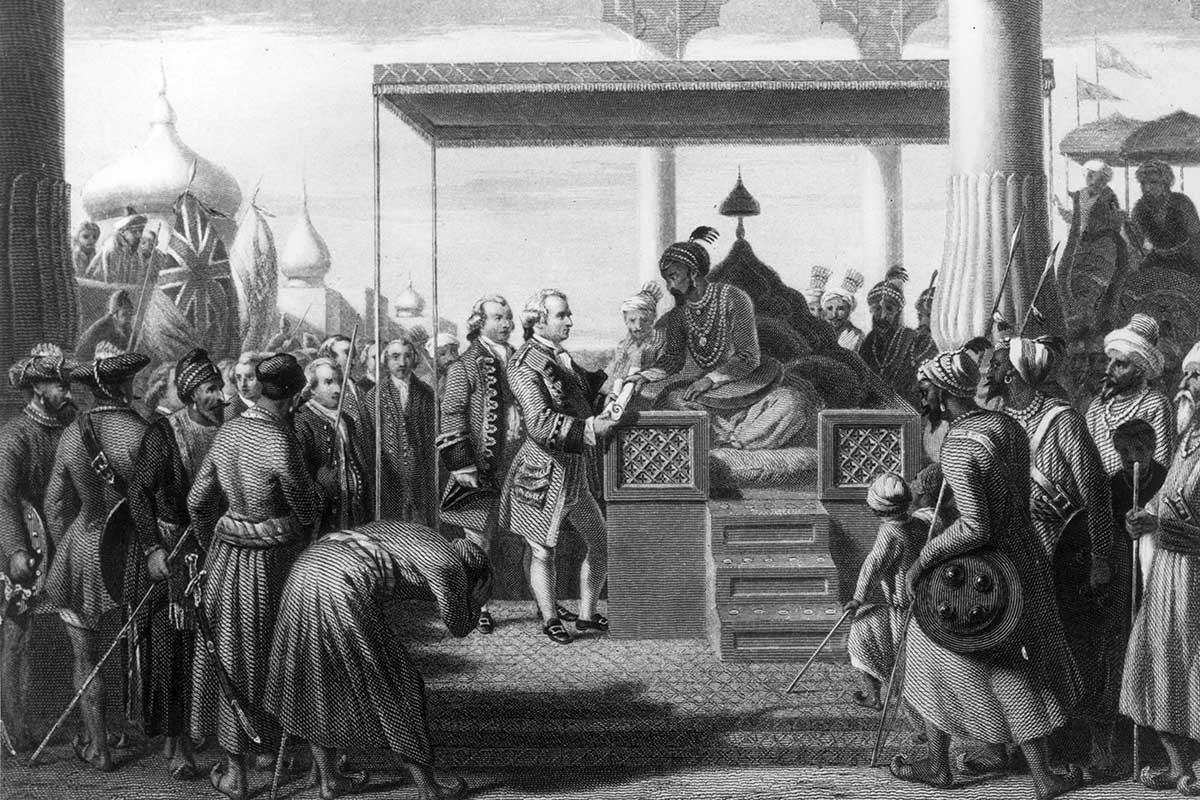

The East India Company had established itself in Calcutta in 1688 but the year 1765 was a landmark year in the history of India & the East India Company. It was in 1765 that the East India Company (EICo) established its first Diwani in Bengal. With this they became incharge of revenue collection and administration of the Bengal (Undivided Bengal, Assam, Orissa).

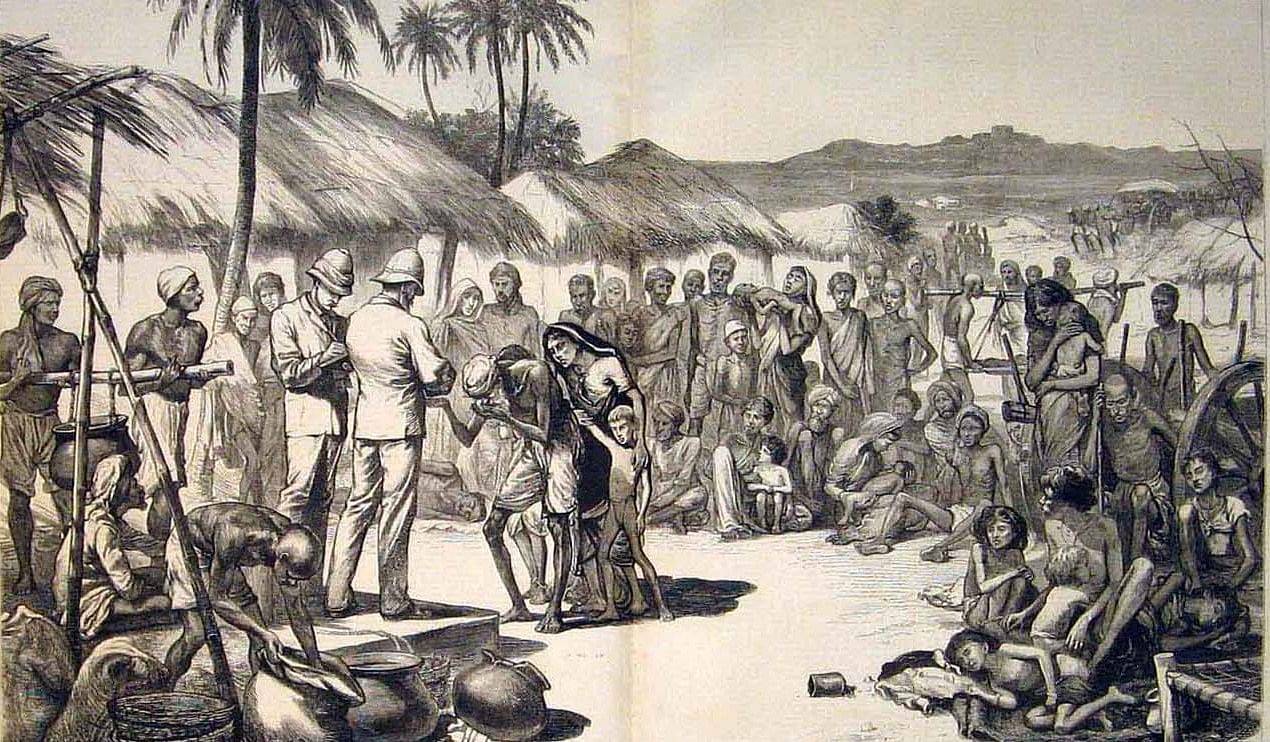

The British increased the Diwani amount by double in the first year they came to power and by ten per cent more the year after that. A number of their policy moves had a negative effect on the economy, one of which was the famine of 1770. The landlords could no longer afford to pay the travelling holy men. Moreover, the British looked upon these Sannyasis as nothing but robbers and dacoits who were out to get a share of their rightful taxes. Also they had a problem with so many men moving about in a band. It made them look suspicious to the foreign government. They actively tried to bar their entry into Bengal and severely restricted their movements within the state. This effectively put a ban on the kind of lifestyle the Sannyasis had been practicing since ancient times.

Like a bull in a china shop the British, with their biblical beliefs of their innate superiority, set about dismantling the age old customs and economic systems. They destroyed the relationship that existed between the owner (zamindar) of the land and men who worked it (the ryot – farmer).

The farmer paid his dues either in kind or cash….usually it was in kind (crop). The farmer supplemented his income with the sale of various items that he produced in the villages (Handicrafts). While paying his taxes the farmer would hold back a portion of the crop for his own use that he would either sell in open market, barter it for other useful items or consume it himself. This unique relation of the ryot with agriculture & handicrafts enabled him to live comfortably and a vibrant barter economy prevailed in the villages. But the British destroyed this system. They forced the ryot to pay his dues in cash. A bad situation was made worse by forcing the ryot to sell only to the East India Company.

The company would buy the crop at ridiculously low prices, force the farmer to pay (in cash) his tax to the company. With no food reserves left, the farmer was forced to buy food grains from the East India Company. The EICo would then sell the same food grains at ridiculously high prices to the poor farmers, impoverishing them further.

Deprived of their crops, forced to buy back the crop at a premium and forcibly stopped from using their skills to make and sell handicraft items ruined the village economy. The perversion of the British did not stop even during the famine of 1770. They did not refrain from torturing the farmers to force them to pay their taxes even during the famine.

To worsen matters, the British continued the practice of taxing Hindu pilgrims. They even increased the taxes on religious pilgrimage which further curtailed the religious life of Hindus.

|

2. The Nawabs - A study in opportunism & Religious hate

During the later half of the 18th century, Bengal was not a peaceful place. Siraj-ud-Daula was a religious fanatic who hated the British as much as he hated his Hindu subjects. His religious bigotry antagonized both Hindu and British. His inexperience led him to overestimate his ability to fight the British forces. His successor, Mir Jafar was a bumbling idiot who antagonized the ascendant British EICo. This led to his removal from the masnad of Bengal and Mir Kasim was out on the masnad. After sometime, the EICo got frustrated by his corrupt incompetence and once again, replaced him with Mir Jafar.

Angered, Mir Kasim sought help from the Nawab of Oudh. Both of them attacked the EICo and at the Battle of Buxar (1764), Hector Munro finally defeated and affirmed British Rule in India.

3. The fakirs

Muslim dervishes and maulvis were a privileged class and they were the third player in the cesspool of discontent, that was Bengal in the 18th century. Belonging to the faith of the rulers and employing power of religious authority over the rulers, the muslim fakirs, dervishes and maulvis were a power center unto themselves. These fakirs & dervishes provided manpower to the armies of the rulers. Call of Jihad given out by these sects would drive the normal muslim follower to take up arms against whosoever was branded a kafir. These fakirs were protected by law and no action could be taken against them. Violence against them was often punishable by death.

Example:- 1659, a sanad was granted to fakir Janab Shah Sultan Hasan Muria by Prince Shah Shuja enabling him to confiscate property, bear arms, force people to provide rations, money etc. No taxes could be charged. And they were protected by law. They killed the Hindu sanyasis, saints, ransacked temples and forcibly converted Hindus. Anyone who resisted was killed and no action could be taken against them. Even retaliation by sanyasis was prohibited. Th British continued with this system allowing the muslim dervishes to murder and maim Hindus, unchecked.

British revenue surveyor J.J. Pemberton described these fakirs as demi-barbarous prone to violence and beggars in name only.

Sanyasis lead the fight back

The fightback of the poor downtrodden mass of impoverished brutalized Hindus was inevitable and it was the sadhus and sanyasis who provided the leadership. Emotionally wrecked, financially ruined and religiously persecuted the Hindus of Bengal were too broken to fight back or so the muslim overlords & british rulers thought. The roaming bands of Sadhus especially The Naga, The Giri & The Puri sects provided emotional support and succor. It was the sanyasis of these sects that took up arms against the muslim & British oppressors. The sanyasis of these sects provided the leadership to the oppressed Hindus and led them to rise against oppression.

The Revolt

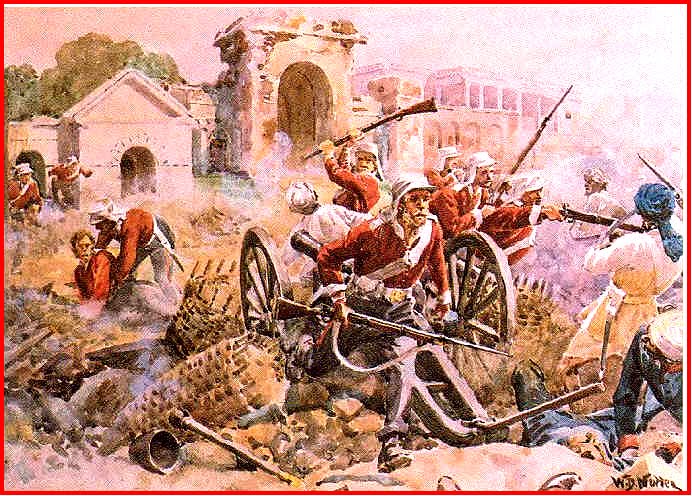

The earliest records of concerted action by Sanyasis speaks of writings of Watt & Howitt (Revenue Surveyors – EICo). They reported attacks by Maratha forces accompanied by the Sanyasis on the treasuries of Kishenghur (Kishangarh) & Burdwan (Bardwan). They report concerted attacks on convoys of the John Company (EICo), preventing them from collecting taxes from farmers and also of punitive raids on camps of John Company. The bands of sanyasis mentioned in the reports are those of the Naga Sadhus. The EICo militia was chased away and forced to seek refuge in Calcutta (Kolkatta).

Another record (1763) written by Warren Hastings speaks of bands of Sanyasis travelling through the country side in Backergunge (Barrakgunj) and captured Hastings’ tax collector Mr. Kelly. He was released after great difficulty. Hastings sought action against the sanyasis but by the time forces could be mustered, the sanyasis had disappeared into the country side.

|

The same year is also know for the infamous siege of EICo’s Dacca Factory (Dhakka). The Dacca District Gazetteer mentions this siege prominently. The factory acted as headquarters for the EICo and stored the company’s treasures in its godowns. Following the attack on the convoy of Kelly, the sanyasis moved towards Dacca (Dhaka) and laid siege on the factory. The manager Ralph Leycester tried to fight but seeing the imminent danger of being overrun by the sanyasi led revolutionaries, he decided to abandon the factory. He tried to take with him the treasure stored their and left the sepoys without orders. The sepoys abandoned the factory and soon it was taken over by the sanyasis. The sanyasis allowed the surrendering sepoys to return home. The retreating manager had left the wounded along the way as he needed soldiers to carry the treasure. These wounded included English and Hindustani soldiers & non combatants. The sanyasis, in the time honoured traditions of Hindustan, treated them and allowed them to return to their lines/homes.

Another instance is of note – the attack on the factory at Rampur Boalia. The attack on this factory remains a mystery as to who attacked it. But the outcome makes clear as to the identity of the attackers. The factory was attacked, looted and its manager Bennett along with other Englishmen were taken prisoner and sent to Mir Kasim, who murdered them.

3 years after this was a period of relative calm. It was this period that the sanyasis tried to take on the Zamindars & English puppets who were as brutal as the British EICo. Sometimes skirmishes also happened between the mendicant Fakirs & Sanyasis. These were triggered due to the jihadist actions of these Fakirs – usually the followers of Majnu Shah & the Madary clan. Driven by religious zeal, these clans would attack the sanyasis and Hindu peasants. But sanyasis had taken up arms and took the battle to the strongholds of these jihadists.

Once again the revolt flared up in 1766. An EICo officer Captain Makenzie exploited the weak zamindars & the public in general. He would force the Hindu zamindars & landed farmers to take loans at exorbitant rates and then force them to pay back by imprisoning, torturing and looting the Hindu victims. The Sanyasis took up arms against him and they forced him to return back to Calcutta. Following this in 1766 Barwell, the company resident at Malda, sent his officer Martyel to the region to buy Fir Trees at easy rates. The exploitation unleashed by him forced the sanyasis to once again take up arms. They killed Martyel. In retaliation, the British sent an expeditionary force under the command of Captain Mackenzie. The sanyasis in the meantime had retreated into the forests of Jalpaiguri where they took refuge in an old mud fort. 1769 Lieutenant Keith got information of presence of sanyasis in the forests of Morung. He led his forces into the forest where in a fierce battle Keith along with his men were defeated and killed. This defeat shook the men of John Company to the core. The company supervisors of Dinajpur, Rangpur, Purania etc panicked and retreated to their forts. From there they sent out frantic messages to Calcutta for reinforcements.

It was now 1770 and the great famine was spreading fast on the once fertile plains of Bengal. As deprivation took hold the atrocities by the British also increased. The sanyasis (500) came out of their jungle abodes and laid siege on the Kandua ghat on Kosi river in Purania. The supervisor of the district G. G. Ducarel sent out his forces under command of Lieutenant Sinclair against the sanyasis. The sanyasis after a brief fight surrendered. The surrendered sanyasis were taken to the fort in Purania. Once inside the fort, the sanyasis claimed to be innocent pilgrims. As their interrogation was going on 5000 sanyasis attacked the fort. The sanyasis inside immediately took up arms and attacked their captors. Under attack from inside and outside the British were defeated and the fort was taken over by the sanyasis.

|

Sanyasi leaders instilled courage and passion that armoured their followers to face the army, even though they were outnumbered one to a hundred. They personified excellence, led by example and, as Bankim would have you believe, thundered mighty speeches that shook the soul:

Yet with all this power now,

Mother wherefore powerless thou?

Holder thou of myriad might,

I salute thee, savior bright,

Thou who dost all foes afright,

Mother, hail!

Thou sole creed and wisdom art,

Thou our very mind and heart,

And the life breath in our bodies,

Thou as strength in arms of men,

Thou as faith in hearts dost reign.

Just as start-ups cannot hope to match up with large corporations in terms of capital and visibility there was no way the sannyasis could match the British army in terms of weapons or numbers. So they played to their strengths. The rebels mainly engaged in guerilla warfare. They knew the countryside better than the back of their hands and had been nomadically travelling their whole lives. They were extremely mobile and could disappear at a moment’s notice. They could also camouflage expertly. This light footedness was their main secret of survival against the military giant that was the British army. The latter had no idea when or where to expect the attacks from.

Governor General Warren Hastings kept sending his best men to contain the rebellion- lieutenant Brennan, Captain Grant, Captain De Mackenzie, etc. But the rebels kept thriving. They did suffer a major defeat at the hands of Major Feltham in 1771, but managed to recover admirably. As long as the Sannyasis conducted their battles covertly, they had a clear upper hand.

Support of the peasants and farmers

Where would the rebels be without the support of the peasants and farmers that the British ruthlessly brutalized? They acted as their intelligence agents and kept them reprised of the Company’s movements and whereabouts, creating a chain of communication not dissimilar to the Telegraph system or the modern social media. The rebels target areas were company kothi’s, zamindari kachhairis of Zamindars loyal to the British rule and the houses of their officials.

The rebels lived in the jungles, foraged for food and dressed in simple handspun weaves. The majority of their looted wealth was reserved for arming themselves to the teeth, training camps for new recruits and providing food and water to the famine ravaged country folk in order to maintain their loyalty to the movement.

|

So, finally company allied with the zamindars against the marauding sannyasis. It was in the end all about revenue. They had the moral justification for expelling and slaughtering the sannyasis on the grounds of protecting the riots. They believed this would prove advantageous for them if they could manage to ensure a lasting victory against the religious mendicants. In addition, the sannyasis posed a threat to the stability of the Company state. By repeatedly looting the kothis and kacharis, they had challenged the very existence of the Company state. They repeatedly raided the countryside. It affected the annual revenue collections. The ‘revenue’ served a dual purpose. On a more pragmatic side, it ensured the solvency of the Company’s mercantile exchequer. However, it also symbolised their legitimacy as Bengal’s rulers. By disrupting the revenue collections, the sannyasis questioned the Company state’s existence and its raison d’ệtre. The Company state had no qualms about defining the rebels.

They considered it imperative to take, serious measures to oppose and prevent the depredations of these freebooters who from year to year from the breaking up of the rains to the months of April, traverse this and the adjacent district in large armed bodies and plunder the inhabitants and with frequent acts of violence and cruelty in often defiance of government.

Thus, we may say that sannyasis were successful in questioning and challenging the very existence of the East India Company. However, the Company state retaliated with military actions. However, it also became clear that the success of the Company state was dependent on a number of factors. For instance, the number of arms and ammunition owned by the troops played a comparatively secondary role. On several occasion, simple matchlocks owned by the rebels bested them. However, what tipped the scale in their favour was the information, and intelligence provided by the harkaras. While the spy system aided them, the hills, jungles the rains, rivers and forts aided sannyasis to sustain their struggle for so long against a better-equipped army. We may conclude that the sannyasi rebellion was an overt resistance movement and it was against the Company state.

|

Though the revolt was big, it was put to an end eventually. The British took brutal steps to suppress the revolt which included:

- Trial and execution of the captured rebels.

- Killing the rebels by torturing them.

- Executing the common people who used to support the rebels.

- Family members of the rebels were arrested and tried. Many were executed unfairly.

- Bribing close persons to gather information.

- Blackmailing the landlords and Nawabs to suppress the revolt in exchange of favor from the company.

The stories are many. Each story is full of valor of the sanyasis – people who had renounced the world. The Naga Sanyasis were the legend that gave sleepless nights to the British. Sannyasi rebellion commenced in the mid-1760s and it took the Company state almost four decades to quell the ‘disturbances’ they caused and the ‘violence’ they perpetuated on the countryside of Bengal. The most affected areas were Purnea, Malda, Dhaka, Dinajpur, Rangpur, Cooch Behar and Murshidabad. Sannyasi rebellion remain immortalised in our imagination.

|

While kingdoms all over the country were crumbling and monarchs were handing over their crowns for fear of persecution, it was these jungle inhabitants who tried to keep enemy forces bay for as long as they possibly could. For that reason history salutes them and Bankim salutes them. And today, so do we.

References:

yourstory.com - By Rakhi Chakraborty

kreately.in - By Vineet Saxena

NSOU-OPEN JOURNAL ISSN: 2581-5415 -Vol.3 No.2 (July 2020)

A multidisciplinary Online Journal of Netaji Subhas Open University, INDIA

Clark, M, The Dasanami Samnyasis, p.14

Farquhar ,J.N., “the organization of the sannyasis of the Vedanta”,pp. 482-83

Clark, M, The Dasanami samnyasis, p.14

Chattopadhyay, B.C. (1938, BS1345). Anandamath, ed. and published by Bandhyopadhyay, B, Kolkata: Bangio Sahitya Parisat

Farquhar, J.N. “the organization of the sannyasis of the Vedanta”,pp.482-83

Sarkar , J.N.(1984). A History of Dasnami Naga Sanyasis, Allahabad: Sri Panchayati Akhara Mahanirvani, p.90

Yogis-monks

Pinch, W.R, Warrior Ascetics, pp. 34-37

Rose H. A, Denzil Ibbetson, Sir; Edward Maclagan.(1991). Lesser known Tribes of N. W. India and Pakistan: Based on the Census reports of 1883, and 1892, Delhi: Amar Prakashan, pp.303-304

National Archives of India , 18th January - 31st May 1773, Foreign Secret, S-NO 23, Vol.9

Cohn,B S. (April-June 1964), 'The Role of the Gossains in the Economy of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century

Upper India', Indian Economic and Social History Review, 1(4), pp.176-177

Steele, A. (1986).The Law and Custom of the Hindu Castes, Delhi: Mittal Publications

Sarkar J.N, A History of Dasnami, p.90

Clark, M, The Dasanamis Samnyasis, pp.73-74

Bhattacharyya, A. (2014). ed. Sannyasi and Fakir Rebellion in Bengal, Jamini Mohan Ghosh Revisited, Delhi: Manohar, p.11

Haq, M I .( 2012).Bange Sufir Prabhab, Kolkata: Vivekananda Book Center, pp. 63-65

Dasgupta, A. K, The Fakir and Sannyasi, pp.10-2

West Bengal State Archives, Raja Shitab Roy’s observation, 3rd August-30th August 1771, Comptrolling Committee of Revenue, Vol.2

NAI. 10th March 1773 Foreign Secret Progs, Vol.9

WBSA, To George Vansittart from J.J. Knightly dated 17th January 1771, 1st January-20th December 1771, Committee of Revenue at Patna, Vol.6

WBSA, 1st January-20th December 1771, Committee of Revenue at Patna, Vol.6

http://www.wbnsou.ac.in/openjournals/Issue/2nd-Issue/July2020/1_Amrita.pdf

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Kartar Singh Sarabha - The Freedom fighter who was Hanged at the age of 19 and inspired Bhagat Singh

- Vinayak Damodar Savarkar – A Misunderstood Legacy

- A Great man Beyond Criticism - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- Unsung Heroine Pritilata Waddedar, Who Shook The British Raj at the age of 21

- 21-yr-old girl Bina Das shot Bengal Governor in her convocation programme at Calcutta University, got Padma Shri but died in penury

- Santi Ghosh and Suniti Choudhury: Two Teenage Freedom Fighters Assassinated British Magistrate

- Tirot Singh: An Unsung Hero of the Khasi Tribe who destroyed British with his skill at Guerrilla Warfare

- Freedom struggle of Gurjars against Britishers at Koonja in 1824: 100s of Gurjars Martyred and 100s Hung in Single Tree

- Dangers of losing our identity: Guru Tegh Bahadur forgotten and Aurangzeb being glorified

- 16 year old freedom fighter Shivdevi Tomar, who killed 17 Britishers and wounded many

- How Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was establishing Hindu Samrajya by concluding centuries of Islamic oppression - Historian GB Mehandale destroys secular propaganda against Hindu Samrajya Divas

- Valiant Marathas and the far-reaching effects of the loss of 3rd battle of Panipat: Jihad of the temple destruction

- On 16th Aug 1946, during Ramzan's 18th day, Direct Action Day aimed to provoke Muslims by mirroring Prophet Muhammad's victory at Badr, Gopal 'Patha', the Lion of Bengal, heroically saved Bengali Hindus & Calcutta from a planned genocide, altering history

- Fearless female sniper Uda Devi, who etched history during the Siege of Lucknow!

- An Artisan Heritage Crafts Village: Indigenous Sustainability of Raghurajpur