More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Join Satyaagrah Social Media

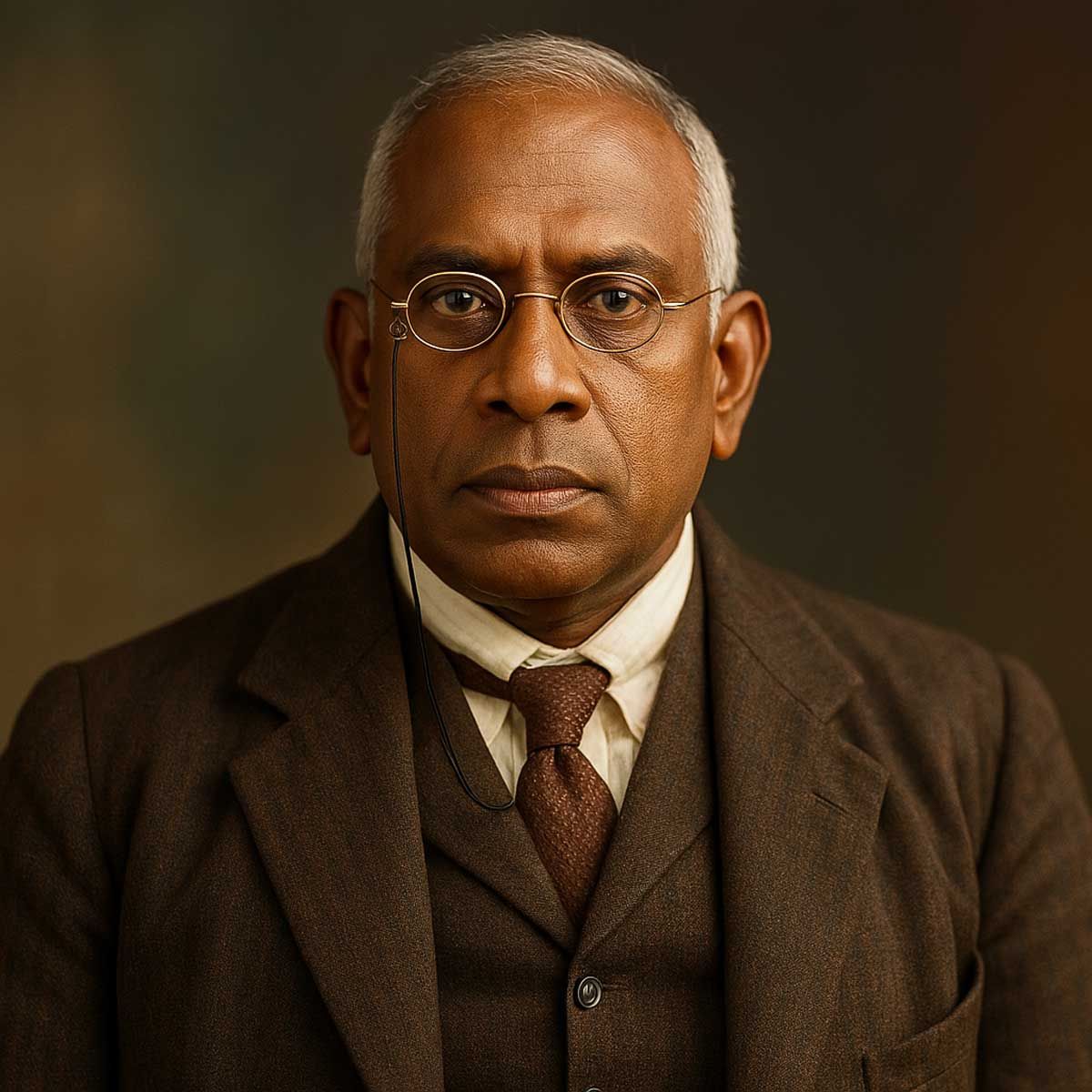

"समुद्रातळ शिवाजी": Behold mighty Kanhoji Angre, born 1669 in Harne, a fearless Maratha Navy hero ruling the Arabian Sea from Surat to Konkan with 80 ships, smashing British, Dutch, and Portuguese foes for 40 years, fortifying Vijayadurg and Alibag

The world has seen many powerful empires rise and fall, with the British Empire being one of the most famous for its control over the seas, a dominance that lasted until the middle of the 20th century. But today, even with all our modern technology where goods are traded in the blink of an eye and people can talk face-to-face from opposite sides of the planet, the seas are once again at the heart of global concerns. Issues like piracy on the water, keeping shipping routes safe, and nations arguing over who controls which part of the ocean are making headlines. For a country like India, this is a big deal because it has a massive coastline stretching “7,517 kilometers”, a long and exposed border that’s hard to protect fully.

|

In India’s long history, its great kingdoms mostly saw the sea as a way to make money through trade, bringing in wealth and goods from far-off lands. Very few thought of using it as a tool for military strength or to expand their influence beyond the shores. Among the major powers that ruled over India, only the Cholas, an ancient South Indian dynasty, and later the European colonizers like the British and Portuguese, truly turned the sea into a source of power. But then, something remarkable happened. During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, when European nations were starting to take over parts of India, one man stood out along the Konkan coast, a rugged stretch of land along western India. His name was Kanhoji Angre, and he became the first homegrown leader to fight for control of India’s coastal waters, protecting them from foreign hands.

Kanhoji Angre wasn’t just any ordinary figure. In Maharashtra, people still remember him fondly as “Samudratla Shivaji” (Shivaji of the seas), a title that shows how much he was respected, like the great Maratha warrior king Shivaji himself. Yet, outside Maharashtra, his name barely gets a mention, which is surprising given what he achieved. This brave naval commander took on some of the toughest European forces—the British, Dutch, and Portuguese—in countless battles across the Indian waters. For over four decades, he stood guard along India’s western coast, striking fear into the hearts of these foreign powers. Every time he led his sailors into battle, they came out on top. He never lost a single fight and kept the coastline safe until the day he died. From the busy port of Surat in the north down to the southern edges of the Konkan region, Kanhoji ruled the waves like a true master.

This incredible Maratha Navy Admiral didn’t just protect the shores—he lifted the pride of Maharashtra’s naval strength and, in a bigger way, showed the world what India could do on the water. At a time when the Mughals ruled much of the land, and the British, Portuguese, and Dutch were flexing their muscles at sea, Kanhoji stood tall and unbeatable. His victories were so impressive that his enemies, frustrated and angry, started calling him a pirate. But he wasn’t just some lawless raider. He captured countless ships belonging to the British, Dutch, and Portuguese, proving his skill and power over and over again.

Kanhoji Angre holds a special place as the first major naval leader in modern Indian history. Through the early years of the 18th century, he kept a firm grip on a coastline that everyone wanted to control. The Europeans—the British, Dutch, and Portuguese—were desperate to rule the trade routes along India’s western shores, and they fought hard to take over. But Kanhoji wouldn’t let them. He was a constant thorn in their side, using his clever strategies to outsmart them every time.

The European powers, annoyed by how he kept disrupting their plans, often labeled him the “Prince of the pirates”. They saw him as a troublemaker because he wouldn’t let them have free rein over the trade routes leading in and out of India’s west coast. But that wasn’t the full story. Kanhoji wasn’t just some rogue acting on his own. He was a loyal supporter of the Maratha rulers, even if he had some freedom to act independently. The Marathas, a powerful warrior group in western India, relied on his brilliant mind and fearless leadership to make sure they were the only local force strong enough to stand up to the Europeans along the coast. In a time when India’s medieval period was fading and European colonization was on the rise, Kanhoji Angre carved out a legacy as a defender of his people’s rights to the sea, a hero whose story deserves to be told far and wide.

India’s coastline stretches across “7,517 kilometers”, a vast and exposed edge that has always played a big role in the country’s story. Long before modern times, India’s ancient rulers understood the value of the seas. Historical records show that empires like the Mauryas, Guptas, and Cholas had their own naval forces patrolling the Indian waters. Among them, the Cholas stood out as true masters of the sea. They didn’t just defend their shores—they went out and conquered far-off lands. Under the leadership of Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I, the Chola Navy led bold expeditions, taking over places like Indonesia, then called “Sri Vijaya”, and the Ceylon islands. These victories showed how strong and well-organized their military and naval power had become, expanding their empire across the seas.

Other rulers left their mark too. Vijaya of Bengal fought and defeated the Ceylonese, setting up his own kingdom on Ceylon. Meanwhile, the Pala Navy kept a sharp eye on the coastal areas around the Bay of Bengal, making sure their waters stayed secure. Down south, Raja Marthanda Varma of Travancore pulled off a stunning win against the Dutch in the Battle of Colachel in 1741, proving that Indian rulers could hold their own against European forces. Even earlier, Chandragupta Maurya’s famous advisor Kautilya, also known as Chanakya, wrote about ocean waterways in his book “Arthashastra”. His words show that Indians were thinking about the sea’s importance—how to use it, protect it, and travel across it—thousands of years ago.

The history of India’s connection to the sea goes back even further, all the way to the time before the Rigveda, one of the oldest sacred texts. In the Rigveda, there’s mention of Varun, the God of water and the vast celestial ocean, who was believed to know all about “sea routes”. Ancient Sanskrit words like “Navadhyaksha”, “Nava Dvipantaragamanam”, “Samudrasamyanam”, and “Matsya Yantra” pop up in old manuscripts, hinting at a deep understanding of ships, sea travel, navigation, and even battles on the water. These terms tell us that ancient Indians weren’t strangers to the sea—they traded, explored, and fought on it. Digging into the past, archaeologists found proof of this at Lothal, a site in coastal Gujarat near today’s Mangrol harbor. The remains there date back to 2300 BC, tying right into the days of the Indus Valley Civilization, one of the world’s earliest urban cultures.

For centuries, India traded with foreign lands not just by land but also by sea. Ships carried spices, cloth, and treasures back and forth, linking India to distant places. But things changed when European powers started showing up in the 17th century. They didn’t just want to trade—they wanted to take over the Indian waters completely. That’s when the Maratha Navy stepped up, under the fearless rule of Chhatrapati Shivaji. His forces became the shield of India’s western coast, ready to take on any foreign ships that dared to challenge them. Shivaji’s sailors were well-trained, and their ships bristled with cannons, always prepared to strike.

Shivaji Maharaj built a mighty fleet with “almost 200 fighting ships of various sizes”. He was smart about keeping watch over the seas too. He set up posts on the Andaman Islands, giving his forces a clear view of any foreign ships coming or going. His navy didn’t mess around—they attacked English, Dutch, and Portuguese vessels, even capturing British ships that crossed their path. The Maratha naval forces were so tough and their ships so well-equipped that Shivaji earned the title “Father of Indian Navy”. It was a name that stuck because he laid the groundwork for something truly special, a naval power that could stand up to anyone.

Among the many brave leaders in the Maratha Navy, one name shines brightest: Kanhoji Angre. With him in charge, enemy forces couldn’t move freely along the western waters for four solid decades. He was a wall they couldn’t break through, a commander who knew the sea like the back of his hand. But he wasn’t alone. Other Maratha heroes like Sidhoji Gurjar, Mainak Bhandari, and Mendhaji Bhatkar also played their part, fighting alongside him to keep the coast safe. Together, they carried forward Shivaji’s dream, making sure India’s waters stayed in Indian hands as long as they could hold the line.

|

Kanhoji Angre: From Humble Beginnings to Naval Legend

Kanhoji Angre’s story starts in 1669, when he was born to Ambabai and Tukoji in the quiet village of Harne, nestled in the Ratnagiri district along the Konkan coast. His family, known as the Angrians with the last name Sankhpal, came from a little place called Angarwadi, hidden in the Mawal hills, just six miles from Poona. Long ago, they earned their name by guarding a small state called “Vir Rana Sank”, a duty that shaped their identity as Sankhpal. Kanhoji’s father, Tukoji, was a man of action. Around 1658, he joined the ranks of the great Chhatrapati Shivaji and proved his worth in several battles. His bravery earned him a command of 200 men and a posting at “Suvarnadurg”, a vital naval stronghold. This fort sat on a small island in the Arabian Sea, between Mumbai and Goa, only twenty miles from the Siddhi’s frontier—a spot that loomed large over the waters. It was here that Kanhoji first blinked into the world, spending his early years watching Maratha ships sail out to challenge enemy fleets. The rough-and-ready Koli sailors, tough but true, taught him the ropes of seamanship, giving him hands-on lessons that would guide him for life.

When Chhatrapati Shivaji passed away, the Maratha Navy, once a powerhouse, started to fade. Shivaji’s son Sambhaji took up the fight, with Sidhoji Gurjar as his Admiral, but Sambhaji’s death in 1690 left the navy in a slump. Then, in 1698, the chief of Satara handed Kanhoji Angre the title of Admiral, or “Surkhel”, after he raided British merchant ships and made off with their riches. His attacks on British, Portuguese, and Dutch vessels didn’t stop there—they kept coming, bold and relentless. By 1700, European records branded him the “most daring pirate”, a name that stuck as he turned their trade routes into a nightmare.

Over time, the Maratha Empire weakened, and in 1707, Shahu Bhonsle, Shivaji’s grandson, became king. Kanhoji had already started taking charge of key naval bases along the coast. Shahu saw his strength and signed a deal, naming him head of the Maratha Navy. But some questioned Kanhoji’s growing power, and the king sent Peshwa Bhyroo Pant with an army to bring him in line. That plan backfired—the Peshwa lost the battle and ended up Kanhoji’s captive. After a second agreement, Kanhoji’s role grew even bigger. He was put in charge of the entire Maratha Navy fleet and named head of “26 forts and fortified places of Maharashtra”, cementing his grip on the region’s defenses.

Kanhoji chose Kolaba as his main base and set up outposts at Vijayadurg, 485 kilometers from Mumbai, as well as Alibag at Mumbai’s southern edge and Purnagad, a port in Ratnagiri. From these spots, he struck at English, Dutch, and Portuguese ships heading to and from the East Indies. For the next forty years, he held firm control over a coastline everyone wanted to claim. His fleet was small—just “80 ships”—and many were basic fishing boats manned by the Kolis, local fishermen who knew every twist and turn of the sea routes. With smart planning and fearless moves, he took on and beat the English, Portuguese, Siddis (backed by Mughals), Dutch, and Sawants of Wadi, proving his mastery time and again.

Back in Shivaji Maharaj’s day, the Maratha Navy was a force to reckon with, boasting “almost 200 fighting ships of various sizes”. After Shivaji’s death, though, it dwindled. Sambhaji kept the fight alive, battling Mughals on land and Portuguese at sea, but his death in 1690 left a void. That’s when Kanhoji stepped up. In 1699, he took over the fleet, bringing it back to life with grit and determination, succeeding Sidhoji Gurjar as the top commander. He made Kolaba his hub and faced down rivals along the west coast—English at Bombay, Portuguese at Goa, Siddis at Janjira, Dutch at Vengurla, and Sawants of Wadi. These were tough foes, but Kanhoji hit the English hardest, making them rue the day they crossed his path.

The odds were stacked against him. The Maratha central authority had crumbled, and the Konkan region lay in ruins after Mughal attacks. Kanhoji had no allies, no spare supplies, and no extra troops to call on. But his forts, surrounded by the sea and tucked away in remote corners, were his saving grace. From these strongholds, he launched raids on enemy ships, targeting their merchant vessels with precision.

|

Naval Expeditions and Achievements of Kanhoji Angre

Kanhoji Angre’s life was a thrilling tale of naval adventures and victories, the kind you don’t often hear about in India’s seafaring history. His career was packed with daring moments that showed his grit and skill. One story tells of a time when he was leading a desperate fight and got captured by the Siddis. Most would’ve given up, but not Kanhoji. For him, “prison walls were no insuperable barrier”—he broke free, swimming back to his struggling comrades at the castle. Once there, he rallied them for a fearless charge, turning the tide with his sheer determination.

His courage wasn’t just talk—it shook even the toughest enemies. One day, he caught a ship carrying the wife of Harvey, the British Governor of Karwar, just two miles off Mumbai’s coast. This wasn’t some lone boat either—it was guarded by English battleships. But Kanhoji’s Maratha warships swooped in, chasing the escorts off like startled birds. His name alone carried such weight that “two other battleships which were in Mumbai Port did not move out at all”, too scared to face him. After negotiating a hefty ransom, he let Harvey’s wife go unharmed, proving he could be fierce yet fair.

To really understand Kanhoji’s sea exploits, you’ve got to see them as part of the Marathas’ bigger fight to protect their land from invaders. A powerful trio—the Siddis, Mughals, and Portuguese—teamed up to crush the Maratha Navy. They threw everything they had at him, but Kanhoji came out on top in the naval clashes that followed. He didn’t just win—he took Sagargad for himself and forced many local rulers along the Konkan coast, places like Kolaba, Khanderi, and Chaul, to pay him tribute. His victories weren’t just about muscle; they were about outsmarting a triple threat that wanted him gone.

Kanhoji wasn’t just a fighter—he was a builder too. He set up dockyards to craft his ships, fitting them with guns and getting them ready to rule the waves. His fleet included “10 grabs and 50 gallivats”, sturdy vessels that packed a punch. Some grabs weighed as much as 400 tons, while the gallivats hit 120 tons—big enough to take on anyone who dared cross him. These ships were his tools, and he wielded them like a master, keeping his coast secure.

By the early 18th century, Kanhoji controlled the whole stretch from Savantwadi to Bombay. Every little inlet, cove, harbor, or river mouth had his mark—fortresses and citadels sprouting up with navigation posts to watch the waters. If you sailed through Maratha territory, you paid a tax called “Chouth”, a clear sign of Kanhoji’s dominance. His bases weren’t just walls and cannons—they were symbols of his unbreakable hold over the sea.

On November 4, 1712, he nabbed the Algerine, an armed yacht belonging to William Aislabie, the British President of Bombay. In the clash, he killed a British chief, Thomas Chown, and took Chown’s wife as a prisoner. After some back-and-forth, he freed the yacht and the woman on February 13, 1713, but only after pocketing a ransom of “30,000 Rupees”. It was a bold move that showed he could hit the British where it hurt and walk away richer.

That same year, 1712, Kanhoji grabbed more British ships—the East Indiamen, Somers, and Grantham—near Goa, snagging them as they sailed from England to Bombay. The British couldn’t handle the losses and ended up handing over “ten forts” to him in 1713 after their defeat. When Charles Boone became Bombay’s new Governor on December 26, 1715, he tried over and over to take Kanhoji down. But every attempt flopped, and in those sea fights, the British lost three ships to Kanhoji’s relentless attacks.

In 1717, Kanhoji struck again, seizing a British ship called the “SUCCESS”. The British hit back, targeting Vijaydurg, his main base, but their attack fell apart. A year later, in 1718, he tightened his grip by blockading Mumbai port and collecting ransom from the trapped ships. Governor Boone wasn’t one to give up—he led an assault on Vijaydurg in 1720, storming the fort with his troops. But Kanhoji’s defenses held strong, and Boone had to limp back home, beaten.

The biggest test came on November 29, 1721, when the British, led by General Robert Cowan, and the Portuguese, under Viceroy Francisco José de Sampaio e Castro, joined forces to take Kanhoji out. It was a massive attack, but Kanhoji’s bravery shone through—they couldn’t touch him and retreated in shambles. The Dutch and Siddis tried their luck too, over and over, but none could match his skill on the water. For forty years, Kanhoji stood tall, turning every challenge into another chapter of triumph.

|

Major Battles Under the Command of Kanhoji Angre

Kanhoji Angre didn’t hold back when it came to pushing Maratha control along the coast—he was bold and fearless, and he could be, because the English East India Company (EIC) wasn’t much of a threat back then. A man named Downing once recalled how weak Bombay was in those days: “was unwalled, and no Grabs or Frigates to protect any thing but the Fishery; except a small Munchew”. It stayed that way until December 1715, when Governor Charles Boone showed up. He shook things up fast, getting the Company to build 25 ships in just a year. These weren’t small boats either—they carried between five and thirty-two guns each, and the whole project cost a hefty “£51,700”. With this new firepower, the British finally had a chance to hit back, hoping to force Kanhoji, the rising Maratha star, to bend to their rules and let them rule the seas again.

Their first move was to strike at Kenerey, an island right at the mouth of Bombay harbor. For four years, it had been under Kanhoji’s watch, handed over to him by Emperor Shahu. The British sent two frigates, the Fame and the Britannia, along with a group of sepoys to hit the fortress of Vingorola from both land and sea. They brought in another frigate, the Revenge, and about a dozen gallivats—small, oar-powered boats with two masts—to drop off the troops. But it didn’t go well. A writer named Biddulph said the force came back after bombing the fort without even getting the soldiers ashore for a real attack. The leader got the blame, called a coward, and was kicked out of his job. Later that year, they tried again, this time with a bigger group—over twenty ships, 2,500 European soldiers, and 1,500 sepoys and topasses. They aimed straight for Kanhoji’s headquarters at the fortress of Geriah. But it flopped too, and all they got out of it was proof the castle couldn’t be taken, plus a heavy toll: “two hundred men killed and three hundred ‘dangerously wounded’”.

The next year, the British went after Khanderi, another Maratha naval base, but they couldn’t budge Kanhoji’s forces from there either. They didn’t give up, though. They gathered another big crew—over twenty ships, 2,500 European soldiers, and 1,500 sepoys and topasses—and took another shot at Geriah. Same story: the fortress stood strong, and the attack fell apart, leaving them with nothing but losses to mourn.

In 1720, Kanhoji landed a solid blow, capturing a British ship called the “CHARLOTTE” and keeping it as his prize. Then came 1721, the year of the boldest attack yet. Starting in November, the British teamed up with the Portuguese to take the island and fortress of Kolaba. This time, they pulled out all the stops, bringing in the Royal Navy led by Commodore Matthews. From then on, no regular Company workers were allowed to lead military missions—only trained fighters. The plan was big: the Portuguese would march from their nearby land in Chaul with 2,500 troops, while the EIC matched that number and threw in five ships, plus the Royal Navy, to hammer Kolaba from the sea and set up cannons on land. If they won, the Portuguese would get Kolaba, and the EIC would claim Geriah. Both sides promised to stick together and not make any side deals with Kanhoji. On the Portuguese end, the Viceroy of Goa, Don Antonio de Castro, and the General of the North took charge. But Kanhoji was ready—he’d gotten word of the plan and called in “25,000 of Shahu’s troops” from the ghats. When the battle kicked off, the Marathas came out on top, proving once again that their naval bases were untouchable.

Fearless and Courageous Kanhoji Angre

Not long after Kanhoji Angre took the reins, he turned the Marathas into a force to be reckoned with, not just on land but out on the open sea—a big shift from how Indian powers usually stuck to the ground. The English East India Company (EIC), on the other hand, had spent nearly a hundred years clawing its way to the top in the region. The Portuguese were still around, but their strength had faded. The Dutch were packing up too, chasing better profits over in the Moluccas. Meanwhile, the Mughals and the EIC had worked out a deal: the Mughals ruled the land, and the EIC called the shots at sea. This setup let the Company control trade routes and slap fees on shipping however they liked. But then came Kanhoji and the Marathas, claiming the same stretch of coast and shaking things up. In 1707 alone, they hit the Company’s shipping out of Surat so hard it cost them “70,000 rupees”. The EIC didn’t waste time—they sent someone to Kanhoji in 1703 with a stern warning: “he cant be permitted searching, molesting or seizing any boates, groabs or other vessels, from what port, harbour, place of what nation soever they may be, bringing provisions, timber or merchandize to Bombay…without breach of that friendship the English nation has always had with Raja Sevajee and all his Captains in subordination to him”. They wanted him to back off and keep their trade flowing smooth.

Kanhoji wasn’t having it. He fired back, standing tall for Maratha rights over the Company’s claims. He told Bombay straight up that the EIC couldn’t boss him around—India was Maratha turf, and they’d have to play by his rules. He laid it out clear: “The Savajees had done many services for the English that never kept their word with him; they had peace with the Portuguese and every one of their ports free to them. The Savajees, had been at war with the Mughals for over forty years and they would continue to seize what boates or other vessel belonging either to the Mogulls vessels from any of his forts or Mallabarr, excepting such as had Conjee Angras passports; the English being at liberty acting as they please”. If a ship didn’t have his pass, he’d go after it—no exceptions unless he said so. The English kept calling him a pirate for it, but to Kanhoji, this was about power and pride. To really get why he did what he did, you’ve got to see him as part of the bigger Maratha struggle, not just some lone raider out for loot.

He wasn’t afraid to ruffle feathers, and that took guts. The Company thought they could lean on their old ties with Shivaji’s legacy to keep Kanhoji in line, but he flipped the script. He reminded them how the Marathas had helped the English plenty of times, only to get empty promises in return. Meanwhile, the Mughals were a constant thorn in the Marathas’ side—forty years of fighting had made that clear. Kanhoji wasn’t about to let the EIC dictate terms when his people were battling for their homeland. His courage shone through every time he sailed out, checking ships and grabbing what didn’t have his approval.

|

Specialty of the Mighty Maratha Navy Under the Command of Kanhoji Angre

The English, Dutch, and Portuguese all tried to take Kanhoji down on land, but those plans fell flat every time. Out on the water, the Company didn’t do much better. Sure, their ships had fancier tech and bigger guns, but they couldn’t keep up with Kanhoji’s fleet. His boats were small, light, and quick as a flash—perfect for dodging and weaving through the waves. The British had these hulking ships that couldn’t chase Kanhoji’s nimble vessels into the shallow spots or twisty estuaries along the coast. That’s where the Marathas had the edge—they knew the waters like the back of their hands and used it to outsmart their enemies every time.

For the Marathas, going toe-to-toe with the English in a full-blown sea war wasn’t smart. If they pushed too hard, the EIC might team up with the Mughals, who were already giving the Marathas a headache with their nonstop attacks. Even without that alliance, starting another big fight would stretch them thin. Instead, they let Kanhoji handle the Company, tossing him extra men when he needed them. It was a cheaper, simpler way to keep things steady—let Kanhoji stir the pot while the Marathas held their ground elsewhere. His little ships didn’t need much to run, and they hit hard where it counted, keeping the EIC on its toes without dragging the whole Maratha force into a messy showdown.

Kanhoji’s navy wasn’t about size—it was about smarts and speed. Those lightweight boats could dart in, strike, and slip away before the Company’s lumbering ships could even turn around. The British kept trying to pin him down, but their heavy vessels got stuck every time they hit the shallows. Kanhoji’s men, on the other hand, thrived in those tricky spots, using the coast’s nooks and crannies to their advantage. It was a cat-and-mouse game, and Kanhoji was always the cat, pouncing when the moment was right. This clever setup let the Marathas tweak the EIC’s nose without risking everything, proving Kanhoji’s fleet was mighty in its own way—small but unstoppable.

Legacy

Kanhoji Angre left this world on July 4, 1729, with a record that’s hard to beat—he never once lost a fight to the English. The East India Company couldn’t brag about snagging even one of his ships at sea either. Kanhoji didn’t just hold his own against the English—he stretched Maratha rule over the waves, taking on the Dutch and Portuguese too. From Surat all the way down to the southern Konkan coast, he made the Arabian Sea his playground, showing everyone what a real sea master looked like.

He wasn’t just about winning battles; Kanhoji had a sharp mind for strategy too. He’s remembered for figuring out that a strong navy—“a Blue Water Navy”—should keep the enemy busy far from shore, stopping them before they could even think about landing. At his peak, he had hundreds of warships under his command, and the British Navy, for all its might, couldn’t do much to stop him. The Maratha Navy ruled the waters, and Kanhoji was the man steering the ship.

People still talk about what he could’ve been. They say, “Had he been in England, like Drake, he would have been knighted and lionised as a national hero, but in India he died merely as an independent ruler who never permitted any foreign ruler to filch even a part of his precious little dominion”. Over there, a fighter like him might’ve gotten medals and statues, but here, he was a local king who refused to let outsiders take even a scrap of what was his. That’s the kind of spirit he carried—fierce, proud, and unbending.

In those early years of the 18th century, Kanhoji’s navy took on the English and Portuguese fleets time after time and sent them packing. They didn’t just win at sea either—their boots hit the ground and beat those same enemies on land too. That’s why Kanhoji’s name is carved deep into the world’s naval history books—not just a footnote, but a headline that won’t fade.

After he was gone, his sons Sekhoji and Sambhaji picked up where he left off, keeping the Maratha naval campaigns alive. Near Alibag, you can still find the Samadhis, the resting places of Kanhoji and his family, standing quietly as a reminder of what they built. It’s a spot where the past feels close, where you can almost hear the echo of those sea battles.

But here’s the thing—Kanhoji wasn’t some rogue pirate, no matter what the English and other shipping bigwigs said. They grumbled and called him a thief because he gave them such a hard time, conveniently forgetting he was the official Admiral of the Maratha Navy. Legal scholar William Hall backs this up, saying Kanhoji doesn’t fit the pirate label. Hall explains it like this: “A pirate either belongs to no state or organised political society, or by the nature of his act he has shown his intention and his power to reject the authority of that to which he is properly subject. So long as acts of violence are done under the authority of the state, or in such way as not to involve its suppression, the state is responsible, and it alone exercises jurisdiction”. Kanhoji was a state man through and through, acting for the Marathas, not some lone outlaw. He stands out as one of Bharat’s early freedom fighters—unbeaten, tough as nails, and a thorn in the side of colonial powers.

Bases

Kanhoji didn’t just fight—he built strongholds to back up his power. In 1698, he set up his first base at Vijayadurg, also called “Victory Fort” (once known as Gheriah), about 425 kilometers from Mumbai. This fort, first raised by Shivaji himself, sits right on the coast with a special entrance carved out so ships could sail straight in from the sea. It was a perfect spot—tough to crack and ready for action.

Then there were the islands of Khanderi and Underi, right off Mumbai’s coast. Kanhoji turned these fortified dots into bases and started charging a tax on every merchant ship that wanted to slip into the harbor. It was his way of saying, “This is our water, and you’ll pay to pass through.”

He didn’t stop there. Toward the end of the 1600s, Kanhoji founded a whole township called Alibag, with Ramnath as the main village back then. He even minted his own money, a silver coin dubbed the “Alibagi rupaiya”. Holding one of those coins must’ve felt like holding a piece of his world—solid proof of his reach.

And then there’s the Andaman Islands. Kanhoji set up a base there too, and folks say he’s the one who tied those islands to India for good. It’s a long way from the Konkan, but that’s how far his vision stretched—out across the sea, planting flags where no one else dared.

|

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- In a historical move ahead of Republic Day on January 26th, the Amar Jawan Jyoti flame at the India Gate would be merged with the flame at the National War Memorial on Friday

- Meet The Dark Knight Of Kargil, Manoj Kumar Pandey, Who Made Rambo Seem Like A Joke

- Tonkham Borpatra Gohain: Ahom general who badly defeated Afghan forces killing Islamic commander Turbak Khan in 1533 CE, battle took place at Duimunisila along banks of mighty Bharali River

- Godse's speech and analysis of fanaticism of Gandhi: Hindus should never be angry against Muslims

- Santi Ghosh and Suniti Choudhury: Two Teenage Freedom Fighters Assassinated British Magistrate

- Operation Trident,1971: How Indian Navy Pulled Off One Of Its Greatest Victories over Pakistan, Karachi burned for seven days

- How Britishers were challenged by 83 year old Ropuiliani in Mizoram in 1892-’93

- "Victory are reserved for those warriors who are willing to pay it's price": One of the greatest and undefeated General Zorawar Singh conquered Laddakh, Tibbat,Gilgit, Skardu, Baltistan and defeated army of Imperial Chinese Tibetans in Dogra-Tibetan War

- "Nak-Kati-Rani": Defying Shah Jahan, Rani Karnavati of Garhwal inflicted unprecedented humiliation on the Mughal army, cutting off their noses; her invincible spirit remain unsung in mainstream history, overshadowing the grand tales of emperors

- Cross Agent and the hidden truth of massacre of Jallianwala Bagh - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- "Tied to the cannon and blown to pieces couldn't deter his loyalty to Ettayapuram King and his devotion to the motherland stood sturdy and unshaken": Veeran Azhagumuthu Kone, Tamil Warrior who rebelled against Britishers 100 years before 1857 war

- A Great man Beyond Criticism - Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Some Hidden Facts)

- British author Tunku Varadarajan tried to tarnish the image of iconic freedom fighter Netaji with reference to Hitler: Sinister agenda to malign the legacy of Netaji from calling him a ‘flawed hero’ to a ‘Nazi sympathiser’

- Vinayak Damodar Savarkar – A Misunderstood Legacy

- Add Vedas and review freedom fighter's portrayal in School textbooks: Parliamentary Committee on Education